Experimental Method In Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The experimental method involves the manipulation of variables to establish cause-and-effect relationships. The key features are controlled methods and the random allocation of participants into controlled and experimental groups .

What is an Experiment?

An experiment is an investigation in which a hypothesis is scientifically tested. An independent variable (the cause) is manipulated in an experiment, and the dependent variable (the effect) is measured; any extraneous variables are controlled.

An advantage is that experiments should be objective. The researcher’s views and opinions should not affect a study’s results. This is good as it makes the data more valid and less biased.

There are three types of experiments you need to know:

1. Lab Experiment

A laboratory experiment in psychology is a research method in which the experimenter manipulates one or more independent variables and measures the effects on the dependent variable under controlled conditions.

A laboratory experiment is conducted under highly controlled conditions (not necessarily a laboratory) where accurate measurements are possible.

The researcher uses a standardized procedure to determine where the experiment will take place, at what time, with which participants, and in what circumstances.

Participants are randomly allocated to each independent variable group.

Examples are Milgram’s experiment on obedience and Loftus and Palmer’s car crash study .

- Strength : It is easier to replicate (i.e., copy) a laboratory experiment. This is because a standardized procedure is used.

- Strength : They allow for precise control of extraneous and independent variables. This allows a cause-and-effect relationship to be established.

- Limitation : The artificiality of the setting may produce unnatural behavior that does not reflect real life, i.e., low ecological validity. This means it would not be possible to generalize the findings to a real-life setting.

- Limitation : Demand characteristics or experimenter effects may bias the results and become confounding variables .

2. Field Experiment

A field experiment is a research method in psychology that takes place in a natural, real-world setting. It is similar to a laboratory experiment in that the experimenter manipulates one or more independent variables and measures the effects on the dependent variable.

However, in a field experiment, the participants are unaware they are being studied, and the experimenter has less control over the extraneous variables .

Field experiments are often used to study social phenomena, such as altruism, obedience, and persuasion. They are also used to test the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings, such as educational programs and public health campaigns.

An example is Holfing’s hospital study on obedience .

- Strength : behavior in a field experiment is more likely to reflect real life because of its natural setting, i.e., higher ecological validity than a lab experiment.

- Strength : Demand characteristics are less likely to affect the results, as participants may not know they are being studied. This occurs when the study is covert.

- Limitation : There is less control over extraneous variables that might bias the results. This makes it difficult for another researcher to replicate the study in exactly the same way.

3. Natural Experiment

A natural experiment in psychology is a research method in which the experimenter observes the effects of a naturally occurring event or situation on the dependent variable without manipulating any variables.

Natural experiments are conducted in the day (i.e., real life) environment of the participants, but here, the experimenter has no control over the independent variable as it occurs naturally in real life.

Natural experiments are often used to study psychological phenomena that would be difficult or unethical to study in a laboratory setting, such as the effects of natural disasters, policy changes, or social movements.

For example, Hodges and Tizard’s attachment research (1989) compared the long-term development of children who have been adopted, fostered, or returned to their mothers with a control group of children who had spent all their lives in their biological families.

Here is a fictional example of a natural experiment in psychology:

Researchers might compare academic achievement rates among students born before and after a major policy change that increased funding for education.

In this case, the independent variable is the timing of the policy change, and the dependent variable is academic achievement. The researchers would not be able to manipulate the independent variable, but they could observe its effects on the dependent variable.

- Strength : behavior in a natural experiment is more likely to reflect real life because of its natural setting, i.e., very high ecological validity.

- Strength : Demand characteristics are less likely to affect the results, as participants may not know they are being studied.

- Strength : It can be used in situations in which it would be ethically unacceptable to manipulate the independent variable, e.g., researching stress .

- Limitation : They may be more expensive and time-consuming than lab experiments.

- Limitation : There is no control over extraneous variables that might bias the results. This makes it difficult for another researcher to replicate the study in exactly the same way.

Key Terminology

Ecological validity.

The degree to which an investigation represents real-life experiences.

Experimenter effects

These are the ways that the experimenter can accidentally influence the participant through their appearance or behavior.

Demand characteristics

The clues in an experiment lead the participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for (e.g., the experimenter’s body language).

Independent variable (IV)

The variable the experimenter manipulates (i.e., changes) is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Dependent variable (DV)

Variable the experimenter measures. This is the outcome (i.e., the result) of a study.

Extraneous variables (EV)

All variables which are not independent variables but could affect the results (DV) of the experiment. EVs should be controlled where possible.

Confounding variables

Variable(s) that have affected the results (DV), apart from the IV. A confounding variable could be an extraneous variable that has not been controlled.

Random Allocation

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable conditions means that all participants should have an equal chance of participating in each condition.

The principle of random allocation is to avoid bias in how the experiment is carried out and limit the effects of participant variables.

Order effects

Changes in participants’ performance due to their repeating the same or similar test more than once. Examples of order effects include:

(i) practice effect: an improvement in performance on a task due to repetition, for example, because of familiarity with the task;

(ii) fatigue effect: a decrease in performance of a task due to repetition, for example, because of boredom or tiredness.

Experimental Psychology: 10 Examples & Definition

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Experimental psychology refers to studying psychological phenomena using scientific methods. Originally, the primary scientific method involved manipulating one variable and observing systematic changes in another variable.

Today, psychologists utilize several types of scientific methodologies.

Experimental psychology examines a wide range of psychological phenomena, including: memory, sensation and perception, cognitive processes, motivation, emotion, developmental processes, in addition to the neurophysiological concomitants of each of these subjects.

Studies are conducted on both animal and human participants, and must comply with stringent requirements and controls regarding the ethical treatment of both.

Definition of Experimental Psychology

Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that utilizes scientific methods to investigate the mind and behavior.

It involves the systematic and controlled study of human and animal behavior through observation and experimentation .

Experimental psychologists design and conduct experiments to understand cognitive processes, perception, learning, memory, emotion, and many other aspects of psychology. They often manipulate variables ( independent variables ) to see how this affects behavior or mental processes (dependent variables).

The findings from experimental psychology research are often used to better understand human behavior and can be applied in a range of contexts, such as education, health, business, and more.

Experimental Psychology Examples

1. The Puzzle Box Studies (Thorndike, 1898) Placing different cats in a box that can only be escaped by pulling a cord, and then taking detailed notes on how long it took for them to escape allowed Edward Thorndike to derive the Law of Effect: actions followed by positive consequences are more likely to occur again, and actions followed by negative consequences are less likely to occur again (Thorndike, 1898).

2. Reinforcement Schedules (Skinner, 1956) By placing rats in a Skinner Box and changing when and how often the rats are rewarded for pressing a lever, it is possible to identify how each schedule results in different behavior patterns (Skinner, 1956). This led to a wide range of theoretical ideas around how rewards and consequences can shape the behaviors of both animals and humans.

3. Observational Learning (Bandura, 1980) Some children watch a video of an adult punching and kicking a Bobo doll. Other children watch a video in which the adult plays nicely with the doll. By carefully observing the children’s behavior later when in a room with a Bobo doll, researchers can determine if television violence affects children’s behavior (Bandura, 1980).

4. The Fallibility of Memory (Loftus & Palmer, 1974) A group of participants watch the same video of two cars having an accident. Two weeks later, some are asked to estimate the rate of speed the cars were going when they “smashed” into each other. Some participants are asked to estimate the rate of speed the cars were going when they “bumped” into each other. Changing the phrasing of the question changes the memory of the eyewitness.

5. Intrinsic Motivation in the Classroom (Dweck, 1990) To investigate the role of autonomy on intrinsic motivation, half of the students are told they are “free to choose” which tasks to complete. The other half of the students are told they “must choose” some of the tasks. Researchers then carefully observe how long the students engage in the tasks and later ask them some questions about if they enjoyed doing the tasks or not.

6. Systematic Desensitization (Wolpe, 1958) A clinical psychologist carefully documents his treatment of a patient’s social phobia with progressive relaxation. At first, the patient is trained to monitor, tense, and relax various muscle groups while viewing photos of parties. Weeks later, they approach a stranger to ask for directions, initiate a conversation on a crowded bus, and attend a small social gathering. The therapist’s notes are transcribed into a scientific report and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

7. Study of Remembering (Bartlett, 1932) Bartlett’s work is a seminal study in the field of memory, where he used the concept of “schema” to describe an organized pattern of thought or behavior. He conducted a series of experiments using folk tales to show that memory recall is influenced by cultural schemas and personal experiences.

8. Study of Obedience (Milgram, 1963) This famous study explored the conflict between obedience to authority and personal conscience. Milgram found that a majority of participants were willing to administer what they believed were harmful electric shocks to a stranger when instructed by an authority figure, highlighting the power of authority and situational factors in driving behavior.

9. Pavlov’s Dog Study (Pavlov, 1927) Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, conducted a series of experiments that became a cornerstone in the field of experimental psychology. Pavlov noticed that dogs would salivate when they saw food. He then began to ring a bell each time he presented the food to the dogs. After a while, the dogs began to salivate merely at the sound of the bell. This experiment demonstrated the principle of “classical conditioning.”

10, Piaget’s Stages of Development (Piaget, 1958) Jean Piaget proposed a theory of cognitive development in children that consists of four distinct stages: the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), where children learn about the world through their senses and motor activities, through to the the formal operational stage (12 years and beyond), where abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking develop. Piaget’s theory is an example of experimental psychology as it was developed through systematic observation and experimentation on children’s problem-solving behaviors .

Types of Research Methodologies in Experimental Psychology

Researchers utilize several different types of research methodologies since the early days of Wundt (1832-1920).

1. The Experiment

The experiment involves the researcher manipulating the level of one variable, called the Independent Variable (IV), and then observing changes in another variable, called the Dependent Variable (DV).

The researcher is interested in determining if the IV causes changes in the DV. For example, does television violence make children more aggressive?

So, some children in the study, called research participants, will watch a show with TV violence, called the treatment group. Others will watch a show with no TV violence, called the control group.

So, there are two levels of the IV: violence and no violence. Next, children will be observed to see if they act more aggressively. This is the DV.

If TV violence makes children more aggressive, then the children that watched the violent show will me more aggressive than the children that watched the non-violent show.

A key requirement of the experiment is random assignment . Each research participant is assigned to one of the two groups in a way that makes it a completely random process. This means that each group will have a mix of children: different personality types, diverse family backgrounds, and range of intelligence levels.

2. The Longitudinal Study

A longitudinal study involves selecting a sample of participants and then following them for years, or decades, periodically collecting data on the variables of interest.

For example, a researcher might be interested in determining if parenting style affects academic performance of children. Parenting style is called the predictor variable , and academic performance is called the outcome variable .

Researchers will begin by randomly selecting a group of children to be in the study. Then, they will identify the type of parenting practices used when the children are 4 and 5 years old.

A few years later, perhaps when the children are 8 and 9, the researchers will collect data on their grades. This process can be repeated over the next 10 years, including through college.

If parenting style has an effect on academic performance, then the researchers will see a connection between the predictor variable and outcome variable.

Children raised with parenting style X will have higher grades than children raised with parenting style Y.

3. The Case Study

The case study is an in-depth study of one individual. This is a research methodology often used early in the examination of a psychological phenomenon or therapeutic treatment.

For example, in the early days of treating phobias, a clinical psychologist may try teaching one of their patients how to relax every time they see the object that creates so much fear and anxiety, such as a large spider.

The therapist would take very detailed notes on how the teaching process was implemented and the reactions of the patient. When the treatment had been completed, those notes would be written in a scientific form and submitted for publication in a scientific journal for other therapists to learn from.

There are several other types of methodologies available which vary different aspects of the three described above. The researcher will select a methodology that is most appropriate to the phenomenon they want to examine.

They also must take into account various practical considerations such as how much time and resources are needed to complete the study. Conducting research always costs money.

People and equipment are needed to carry-out every study, so researchers often try to obtain funding from their university or a government agency.

Origins and Key Developments in Experimental Psychology

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (1832-1920) is considered one of the fathers of modern psychology. He was a physiologist and philosopher and helped establish psychology as a distinct discipline (Khaleefa, 1999).

In 1879 he established the world’s first psychology research lab at the University of Leipzig. This is considered a key milestone for establishing psychology as a scientific discipline. In addition to being the first person to use the term “psychologist,” to describe himself, he also founded the discipline’s first scientific journal Philosphische Studien in 1883.

Another notable figure in the development of experimental psychology is Ernest Weber . Trained as a physician, Weber studied sensation and perception and created the first quantitative law in psychology.

The equation denotes how judgments of sensory differences are relative to previous levels of sensation, referred to as the just-noticeable difference (jnd). This is known today as Weber’s Law (Hergenhahn, 2009).

Gustav Fechner , one of Weber’s students, published the first book on experimental psychology in 1860, titled Elemente der Psychophysik. His worked centered on the measurement of psychophysical facets of sensation and perception, with many of his methods still in use today.

The first American textbook on experimental psychology was Elements of Physiological Psychology, published in 1887 by George Trumball Ladd .

Ladd also established a psychology lab at Yale University, while Stanley Hall and Charles Sanders continued Wundt’s work at a lab at Johns Hopkins University.

In the late 1800s, Charles Pierce’s contribution to experimental psychology is especially noteworthy because he invented the concept of random assignment (Stigler, 1992; Dehue, 1997).

Go Deeper: 15 Random Assignment Examples

This procedure ensures that each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any of the experimental groups (e.g., treatment or control group). This eliminates the influence of confounding factors related to inherent characteristics of the participants.

Random assignment is a fundamental criterion for a study to be considered a valid experiment.

From there, experimental psychology flourished in the 20th century as a science and transformed into an approach utilized in cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, and social psychology .

Today, the term experimental psychology refers to the study of a wide range of phenomena and involves methodologies not limited to the manipulation of variables.

The Scientific Process and Experimental Psychology

The one thing that makes psychology a science and distinguishes it from its roots in philosophy is the reliance upon the scientific process to answer questions. This makes psychology a science was the main goal of its earliest founders such as Wilhelm Wundt.

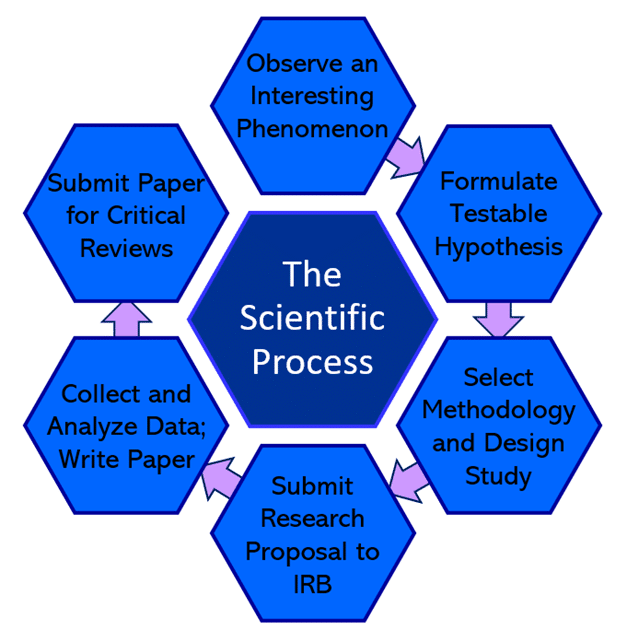

There are numerous steps in the scientific process, outlined in the graphic below.

1. Observation

First, the scientist observes an interesting phenomenon that sparks a question. For example, are the memories of eyewitnesses really reliable, or are they subject to bias or unintentional manipulation?

2. Hypothesize

Next, this question is converted into a testable hypothesis. For instance: the words used to question a witness can influence what they think they remember.

3. Devise a Study

Then the researcher(s) select a methodology that will allow them to test that hypothesis. In this case, the researchers choose the experiment, which will involve randomly assigning some participants to different conditions.

In one condition, participants are asked a question that implies a certain memory (treatment group), while other participants are asked a question which is phrased neutrally and does not imply a certain memory (control group).

The researchers then write a proposal that describes in detail the procedures they want to use, how participants will be selected, and the safeguards they will employ to ensure the rights of the participants.

That proposal is submitted to an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB is comprised of a panel of researchers, community representatives, and other professionals that are responsible for reviewing all studies involving human participants.

4. Conduct the Study

If the IRB accepts the proposal, then the researchers may begin collecting data. After the data has been collected, it is analyzed using a software program such as SPSS.

Those analyses will either support or reject the hypothesis. That is, either the participants’ memories were affected by the wording of the question, or not.

5. Publish the study

Finally, the researchers write a paper detailing their procedures and results of the statistical analyses. That paper is then submitted to a scientific journal.

The lead editor of that journal will then send copies of the paper to 3-5 experts in that subject. Each of those experts will read the paper and basically try to find as many things wrong with it as possible. Because they are experts, they are very good at this task.

After reading those critiques, most likely, the editor will send the paper back to the researchers and require that they respond to the criticisms, collect more data, or reject the paper outright.

In some cases, the study was so well-done that the criticisms were minimal and the editor accepts the paper. It then gets published in the scientific journal several months later.

That entire process can easily take 2 years, usually more. But, the findings of that study went through a very rigorous process. This means that we can have substantial confidence that the conclusions of the study are valid.

Experimental psychology refers to utilizing a scientific process to investigate psychological phenomenon.

There are a variety of methods employed today. They are used to study a wide range of subjects, including memory, cognitive processes, emotions and the neurophysiological basis of each.

The history of psychology as a science began in the 1800s primarily in Germany. As interest grew, the field expanded to the United States where several influential research labs were established.

As more methodologies were developed, the field of psychology as a science evolved into a prolific scientific discipline that has provided invaluable insights into human behavior.

Bartlett, F. C., & Bartlett, F. C. (1995). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology . Cambridge university press.

Dehue, T. (1997). Deception, efficiency, and random groups: Psychology and the gradual origination of the random group design. Isis , 88 (4), 653-673.

Ebbinghaus, H. (2013). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of neurosciences , 20 (4), 155.

Hergenhahn, B. R. (2009). An introduction to the history of psychology. Belmont. CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning .

Khaleefa, O. (1999). Who is the founder of psychophysics and experimental psychology? American Journal of Islam and Society , 16 (2), 1-26.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of auto-mobile destruction : An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal behavior , 13, 585-589.

Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes . Dover, New York.

Piaget, J. (1959). The language and thought of the child (Vol. 5). Psychology Press.

Piaget, J., Fraisse, P., & Reuchlin, M. (2014). Experimental psychology its scope and method: Volume I (Psychology Revivals): History and method . Psychology Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1956). A case history in scientlfic method. American Psychologist, 11 , 221-233

Stigler, S. M. (1992). A historical view of statistical concepts in psychology and educational research. American Journal of Education , 101 (1), 60-70.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Review Monograph Supplement 2 .

Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Appendix: Images reproduced as Text

Definition: Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on conducting systematic and controlled experiments to study human behavior and cognition.

Overview: Experimental psychology aims to gather empirical evidence and explore cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Experimental psychologists utilize various research methods, including laboratory experiments, surveys, and observations, to investigate topics such as perception, memory, learning, motivation, and social behavior .

Example: The Pavlov’s Dog experimental psychology experiment used scientific methods to develop a theory about how learning and association occur in animals. The same concepts were subsequently used in the study of humans, wherein psychology-based ideas about learning were developed. Pavlov’s use of the empirical evidence was foundational to the study’s success.

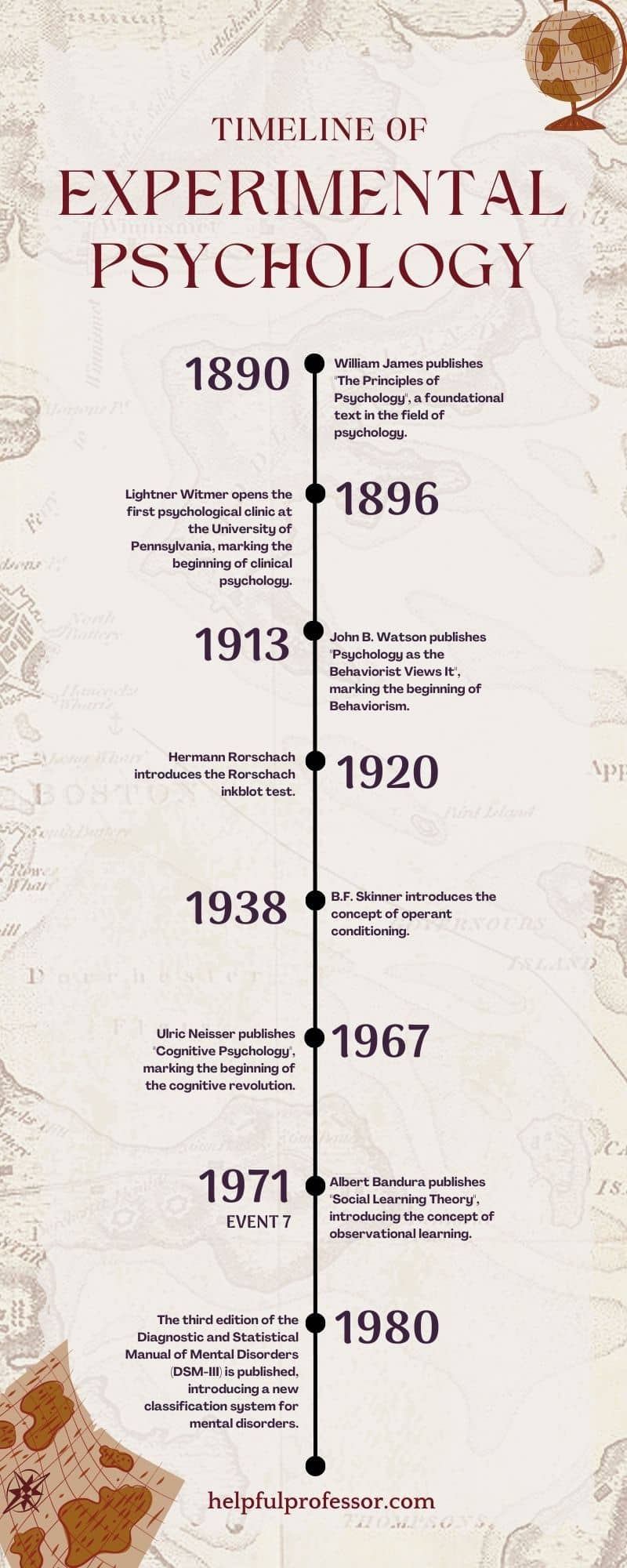

Experimental Psychology Milestones:

1890: William James publishes “The Principles of Psychology”, a foundational text in the field of psychology.

1896: Lightner Witmer opens the first psychological clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, marking the beginning of clinical psychology.

1913: John B. Watson publishes “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It”, marking the beginning of Behaviorism.

1920: Hermann Rorschach introduces the Rorschach inkblot test.

1938: B.F. Skinner introduces the concept of operant conditioning .

1967: Ulric Neisser publishes “Cognitive Psychology” , marking the beginning of the cognitive revolution.

1980: The third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) is published, introducing a new classification system for mental disorders.

The Scientific Process

- Observe an interesting phenomenon

- Formulate testable hypothesis

- Select methodology and design study

- Submit research proposal to IRB

- Collect and analyzed data; write paper

- Submit paper for critical reviews

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Experimental Method in Psychology: Principles, Applications, and Limitations

As the cornerstone of psychological research, the experimental method has revolutionized our understanding of the human mind, behavior, and the intricate workings of the brain. This powerful approach has paved the way for countless breakthroughs in our quest to unravel the mysteries of human cognition and behavior. From the early days of Wilhelm Wundt’s pioneering work to the cutting-edge neuroscience experiments of today, the experimental method has been the driving force behind our ever-expanding knowledge of psychology.

But what exactly is the experimental method, and why is it so crucial to psychological research? Let’s dive into the fascinating world of experimental psychology and explore its principles, applications, and limitations.

The Birth of Experimental Psychology: A Journey Through Time

Picture this: It’s the late 19th century, and psychology is still in its infancy. Enter Wilhelm Wundt, a German physiologist with a burning curiosity about the human mind. In 1879, Wundt established the first psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig, marking the birth of experimental psychology as we know it today.

Wundt’s groundbreaking work laid the foundation for a more scientific approach to studying the mind. He believed that mental processes could be measured and analyzed systematically, just like physical phenomena. This radical idea sparked a revolution in psychological research, inspiring generations of scientists to explore the depths of human cognition and behavior through carefully controlled experiments.

As the field of psychology evolved, so did the experimental method. Researchers refined their techniques, developed new tools, and tackled increasingly complex questions about the human mind. Today, laboratory experiments in psychology are sophisticated endeavors that employ cutting-edge technology and rigorous methodologies to unveil the science of human behavior.

The Building Blocks of Experimental Design: A Recipe for Scientific Discovery

At its core, the experimental method in psychology is all about uncovering cause-and-effect relationships. But how do researchers go about designing experiments that can reliably answer their questions? Let’s break down the key components of an experiment in psychology :

1. Variables: The stars of the show in any experiment are the variables. These are the factors that researchers manipulate or measure to test their hypotheses. There are three main types of variables:

– Independent variables: These are the factors that researchers deliberately manipulate to observe their effects on behavior or cognition. – Dependent variables: These are the outcomes or behaviors that researchers measure in response to changes in the independent variables. – Control variables: These are factors that researchers keep constant to ensure that they don’t interfere with the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

2. Hypothesis: Every good experiment starts with a clear, testable prediction about the relationship between variables. This hypothesis serves as the guiding light for the entire research process.

3. Experimental design: Researchers must carefully plan how they’ll manipulate variables, assign participants to groups, and collect data. This step is crucial for ensuring that the experiment can reliably answer the research question.

4. Participants: The people (or animals) who take part in the experiment are the lifeblood of psychological research. Careful selection and assignment of participants help ensure that the results are generalizable to the broader population.

5. Procedure: This is the step-by-step plan for conducting the experiment, including instructions for participants, data collection methods, and any necessary equipment or materials.

6. Data analysis: Once the experiment is complete, researchers use statistical techniques to make sense of their findings and determine whether their hypothesis was supported.

By carefully considering each of these components, researchers can design experiments that shed light on the complexities of human behavior and cognition.

The Art and Science of Experimental Design: Crafting the Perfect Study

Designing a psychological experiment is both an art and a science. It requires creativity, critical thinking, and a deep understanding of scientific principles. Let’s explore some of the key considerations that researchers must keep in mind when designing their studies:

1. Establishing cause-and-effect relationships: The holy grail of experimental psychology is uncovering causal relationships between variables. To do this, researchers must carefully manipulate independent variables while controlling for potential confounds.

2. Controlling for confounding variables: In the messy world of human behavior, countless factors can influence our thoughts and actions. Researchers must be vigilant in identifying and controlling for these potential confounds to ensure that their results are valid.

3. Randomization: This powerful technique helps reduce bias by ensuring that participants have an equal chance of being assigned to different experimental conditions. It’s like shuffling a deck of cards before dealing – it helps level the playing field.

4. Types of experimental designs: Researchers can choose from various experimental designs, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The two main categories are:

– Between-subjects designs: Different groups of participants are exposed to different conditions. – Within-subjects designs: The same participants are exposed to multiple conditions.

The choice of design depends on the research question, practical considerations, and the nature of the variables being studied.

From Hypothesis to Discovery: The Journey of a Psychological Experiment

Now that we’ve explored the building blocks of experimental design, let’s walk through the steps of conducting a psychological experiment. It’s a journey filled with excitement, challenges, and the potential for groundbreaking discoveries.

1. Formulating a research question and hypothesis: Every great experiment starts with curiosity. Researchers identify a gap in our understanding of human behavior or cognition and develop a specific, testable hypothesis to address it.

2. Designing the experimental procedure: This is where the rubber meets the road. Researchers must carefully plan every aspect of their study, from the precise wording of instructions to the timing of each task.

3. Selecting and assigning participants: Finding the right participants is crucial for ensuring that the results are meaningful and generalizable. Researchers must consider factors like sample size, demographic characteristics, and recruitment methods.

4. Collecting and analyzing data: With everything in place, it’s time to run the experiment and gather data. This process can range from simple pencil-and-paper surveys to complex neuroimaging studies.

5. Drawing conclusions and reporting results: Once the data is collected, researchers use statistical analyses to determine whether their hypothesis was supported. They then interpret their findings in the context of existing theories and previous research.

This journey from hypothesis to discovery is at the heart of scientific progress in psychology. Each experiment, no matter how small, contributes to our growing understanding of the human mind and behavior.

Experiments in Action: Exploring the Diverse Landscape of Psychological Research

The experimental method is a versatile tool that can be applied to a wide range of psychological phenomena. Let’s take a whirlwind tour of some fascinating experiments across different areas of psychology:

1. Cognitive psychology: Researchers in this field use experiments to explore mental processes like memory, attention, and decision-making. For example, the famous “cocktail party effect” experiments revealed our remarkable ability to focus on a single conversation in a noisy room.

2. Social psychology: Experiments in this area shed light on how our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by others. The classic Milgram obedience experiments, while ethically controversial, revealed startling insights into human compliance with authority.

3. Developmental psychology: Researchers use clever experimental designs to study how children’s minds grow and change over time. Jean Piaget’s conservation tasks, for instance, revealed fascinating insights into children’s understanding of quantity and volume.

4. Clinical psychology: Experiments in this field help us understand mental health disorders and develop effective treatments. For example, studies on exposure therapy have shown its effectiveness in treating phobias and anxiety disorders.

5. Neuroscience and behavioral experiments: By combining behavioral tasks with brain imaging techniques, researchers can explore the neural basis of psychological phenomena. The famous “split-brain” experiments, for instance, revealed fascinating insights into how the two hemispheres of the brain work together.

These examples barely scratch the surface of the diverse and exciting world of psychological experiments. Each study contributes to our growing understanding of the human mind and behavior, piece by piece.

The Power and Promise of Experimental Psychology

The experimental method has numerous advantages that make it a cornerstone of psychological research:

1. High internal validity: By carefully controlling variables, experiments allow researchers to draw strong conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships.

2. Ability to establish causality: This is perhaps the most significant advantage of experiments. They allow us to move beyond mere correlation and identify true causal relationships.

3. Replicability and generalizability: Well-designed experiments can be replicated by other researchers, helping to confirm and extend findings. This is crucial for building a solid foundation of scientific knowledge.

4. Precision in measuring variables: Experiments allow for precise manipulation and measurement of variables, leading to more accurate and reliable results.

5. Contribution to theory development and testing: Experiments play a crucial role in testing and refining psychological theories, driving the field forward.

The experimental effects in psychology have had a profound impact on our understanding of human behavior and cognition. From uncovering the basic principles of learning and memory to revealing the complexities of social influence, experiments have been at the forefront of psychological discovery.

Navigating the Challenges: Limitations and Ethical Considerations

While the experimental method is incredibly powerful, it’s not without its limitations and ethical challenges. As researchers, we must be aware of these issues and work to address them:

1. Potential for artificial settings: Laboratory experiments may create environments that don’t accurately reflect real-world situations, potentially limiting the experimental realism in psychology .

2. Ethical concerns: Experiments involving human participants must adhere to strict ethical guidelines to protect participants’ well-being and rights. The infamous Stanford Prison Experiment serves as a cautionary tale about the potential for ethical breaches in psychological research.

3. Challenges in studying complex phenomena: Some aspects of human behavior and cognition are difficult to study in controlled laboratory settings, requiring researchers to be creative in their experimental designs.

4. Potential researcher bias and demand characteristics: Experimenters must be careful not to inadvertently influence participants’ behavior through subtle cues or expectations.

5. Time and resource constraints: Well-designed experiments can be time-consuming and expensive, potentially limiting the scope of research questions that can be addressed.

These disadvantages of experiments in psychology highlight the need for researchers to be thoughtful and creative in their approach to studying human behavior and cognition.

The Future of Experimental Psychology: Pushing the Boundaries of Discovery

As we look to the future, the experimental method in psychology continues to evolve and adapt to new challenges and opportunities. Emerging technologies, such as virtual reality and advanced brain imaging techniques, are opening up exciting new avenues for research.

Researchers are also working to address some of the limitations of traditional experiments by developing innovative methodologies. For example, ecological momentary assessment allows researchers to study behavior in real-world settings, bridging the gap between laboratory experiments and naturalistic observation.

The future of experimental psychology lies in striking a balance between rigorous scientific methodology and real-world applicability. By combining the strengths of experimental designs with other research approaches, psychologists can continue to push the boundaries of our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

In conclusion, the experimental method remains a powerful and indispensable tool in psychological research. From its humble beginnings in Wilhelm Wundt’s laboratory to the cutting-edge neuroscience experiments of today, this approach has revolutionized our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

As we continue to unravel the mysteries of human cognition and behavior, the experimental method will undoubtedly play a crucial role. By embracing new technologies, addressing ethical concerns, and pushing the boundaries of experimental design, researchers can ensure that this cornerstone of psychological research remains as relevant and impactful as ever.

So, the next time you hear about a fascinating psychological study, take a moment to appreciate the careful planning, creativity, and scientific rigor that went into its design. Who knows? Maybe you’ll be inspired to design your own experiment and contribute to our ever-growing understanding of the human mind.

References:

1. Coolican, H. (2018). Research methods and statistics in psychology. Routledge.

2. Goodwin, C. J., & Goodwin, K. A. (2016). Research in psychology: Methods and design. John Wiley & Sons.

3. Kantowitz, B. H., Roediger III, H. L., & Elmes, D. G. (2014). Experimental psychology. Cengage Learning.

4. Leary, M. R. (2011). Introduction to behavioral research methods. Pearson.

5. Martin, D. W. (2007). Doing psychology experiments. Cengage Learning.

6. Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

7. Shaughnessy, J. J., Zechmeister, E. B., & Zechmeister, J. S. (2015). Research methods in psychology. McGraw-Hill Education.

8. Smith, R. A., & Davis, S. F. (2012). The psychologist as detective: An introduction to conducting research in psychology. Pearson.

9. Stanovich, K. E. (2013). How to think straight about psychology. Pearson.

10. Weiten, W. (2016). Psychology: Themes and variations. Cengage Learning.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Brain Samples: Unlocking the Secrets of Neuroscience

Discover Psychology Impact Factor: Exploring the Journal’s Influence and Significance

Confidence Intervals in Psychology: Enhancing Statistical Interpretation and Research Validity

Control Condition in Psychology: Definition, Purpose, and Applications

Dependent Variables in Psychology: Definition, Examples, and Importance

Debriefing in Psychology: Definition, Purpose, and Techniques

Correlation in Psychology: Definition, Types, and Applications

Data Collection Methods in Psychology: Essential Techniques for Researchers

Histogram in Psychology: Definition, Applications, and Significance

Dimensional vs Categorical Approach in Psychology: Comparing Methods of Classification

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How the Experimental Method Works in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amanda Tust is an editor, fact-checker, and writer with a Master of Science in Journalism from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Amanda-Tust-1000-ffe096be0137462fbfba1f0759e07eb9.jpg)

sturti/Getty Images

The Experimental Process

Types of experiments, potential pitfalls of the experimental method.

The experimental method is a type of research procedure that involves manipulating variables to determine if there is a cause-and-effect relationship. The results obtained through the experimental method are useful but do not prove with 100% certainty that a singular cause always creates a specific effect. Instead, they show the probability that a cause will or will not lead to a particular effect.

At a Glance

While there are many different research techniques available, the experimental method allows researchers to look at cause-and-effect relationships. Using the experimental method, researchers randomly assign participants to a control or experimental group and manipulate levels of an independent variable. If changes in the independent variable lead to changes in the dependent variable, it indicates there is likely a causal relationship between them.

What Is the Experimental Method in Psychology?

The experimental method involves manipulating one variable to determine if this causes changes in another variable. This method relies on controlled research methods and random assignment of study subjects to test a hypothesis.

For example, researchers may want to learn how different visual patterns may impact our perception. Or they might wonder whether certain actions can improve memory . Experiments are conducted on many behavioral topics, including:

The scientific method forms the basis of the experimental method. This is a process used to determine the relationship between two variables—in this case, to explain human behavior .

Positivism is also important in the experimental method. It refers to factual knowledge that is obtained through observation, which is considered to be trustworthy.

When using the experimental method, researchers first identify and define key variables. Then they formulate a hypothesis, manipulate the variables, and collect data on the results. Unrelated or irrelevant variables are carefully controlled to minimize the potential impact on the experiment outcome.

History of the Experimental Method

The idea of using experiments to better understand human psychology began toward the end of the nineteenth century. Wilhelm Wundt established the first formal laboratory in 1879.

Wundt is often called the father of experimental psychology. He believed that experiments could help explain how psychology works, and used this approach to study consciousness .

Wundt coined the term "physiological psychology." This is a hybrid of physiology and psychology, or how the body affects the brain.

Other early contributors to the development and evolution of experimental psychology as we know it today include:

- Gustav Fechner (1801-1887), who helped develop procedures for measuring sensations according to the size of the stimulus

- Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894), who analyzed philosophical assumptions through research in an attempt to arrive at scientific conclusions

- Franz Brentano (1838-1917), who called for a combination of first-person and third-person research methods when studying psychology

- Georg Elias Müller (1850-1934), who performed an early experiment on attitude which involved the sensory discrimination of weights and revealed how anticipation can affect this discrimination

Key Terms to Know

To understand how the experimental method works, it is important to know some key terms.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the effect that the experimenter is measuring. If a researcher was investigating how sleep influences test scores, for example, the test scores would be the dependent variable.

Independent Variable

The independent variable is the variable that the experimenter manipulates. In the previous example, the amount of sleep an individual gets would be the independent variable.

A hypothesis is a tentative statement or a guess about the possible relationship between two or more variables. In looking at how sleep influences test scores, the researcher might hypothesize that people who get more sleep will perform better on a math test the following day. The purpose of the experiment, then, is to either support or reject this hypothesis.

Operational definitions are necessary when performing an experiment. When we say that something is an independent or dependent variable, we must have a very clear and specific definition of the meaning and scope of that variable.

Extraneous Variables

Extraneous variables are other variables that may also affect the outcome of an experiment. Types of extraneous variables include participant variables, situational variables, demand characteristics, and experimenter effects. In some cases, researchers can take steps to control for extraneous variables.

Demand Characteristics

Demand characteristics are subtle hints that indicate what an experimenter is hoping to find in a psychology experiment. This can sometimes cause participants to alter their behavior, which can affect the results of the experiment.

Intervening Variables

Intervening variables are factors that can affect the relationship between two other variables.

Confounding Variables

Confounding variables are variables that can affect the dependent variable, but that experimenters cannot control for. Confounding variables can make it difficult to determine if the effect was due to changes in the independent variable or if the confounding variable may have played a role.

Psychologists, like other scientists, use the scientific method when conducting an experiment. The scientific method is a set of procedures and principles that guide how scientists develop research questions, collect data, and come to conclusions.

The five basic steps of the experimental process are:

- Identifying a problem to study

- Devising the research protocol

- Conducting the experiment

- Analyzing the data collected

- Sharing the findings (usually in writing or via presentation)

Most psychology students are expected to use the experimental method at some point in their academic careers. Learning how to conduct an experiment is important to understanding how psychologists prove and disprove theories in this field.

There are a few different types of experiments that researchers might use when studying psychology. Each has pros and cons depending on the participants being studied, the hypothesis, and the resources available to conduct the research.

Lab Experiments

Lab experiments are common in psychology because they allow experimenters more control over the variables. These experiments can also be easier for other researchers to replicate. The drawback of this research type is that what takes place in a lab is not always what takes place in the real world.

Field Experiments

Sometimes researchers opt to conduct their experiments in the field. For example, a social psychologist interested in researching prosocial behavior might have a person pretend to faint and observe how long it takes onlookers to respond.

This type of experiment can be a great way to see behavioral responses in realistic settings. But it is more difficult for researchers to control the many variables existing in these settings that could potentially influence the experiment's results.

Quasi-Experiments

While lab experiments are known as true experiments, researchers can also utilize a quasi-experiment. Quasi-experiments are often referred to as natural experiments because the researchers do not have true control over the independent variable.

A researcher looking at personality differences and birth order, for example, is not able to manipulate the independent variable in the situation (personality traits). Participants also cannot be randomly assigned because they naturally fall into pre-existing groups based on their birth order.

So why would a researcher use a quasi-experiment? This is a good choice in situations where scientists are interested in studying phenomena in natural, real-world settings. It's also beneficial if there are limits on research funds or time.

Field experiments can be either quasi-experiments or true experiments.

Examples of the Experimental Method in Use

The experimental method can provide insight into human thoughts and behaviors, Researchers use experiments to study many aspects of psychology.

A 2019 study investigated whether splitting attention between electronic devices and classroom lectures had an effect on college students' learning abilities. It found that dividing attention between these two mediums did not affect lecture comprehension. However, it did impact long-term retention of the lecture information, which affected students' exam performance.

An experiment used participants' eye movements and electroencephalogram (EEG) data to better understand cognitive processing differences between experts and novices. It found that experts had higher power in their theta brain waves than novices, suggesting that they also had a higher cognitive load.

A study looked at whether chatting online with a computer via a chatbot changed the positive effects of emotional disclosure often received when talking with an actual human. It found that the effects were the same in both cases.

One experimental study evaluated whether exercise timing impacts information recall. It found that engaging in exercise prior to performing a memory task helped improve participants' short-term memory abilities.

Sometimes researchers use the experimental method to get a bigger-picture view of psychological behaviors and impacts. For example, one 2018 study examined several lab experiments to learn more about the impact of various environmental factors on building occupant perceptions.

A 2020 study set out to determine the role that sensation-seeking plays in political violence. This research found that sensation-seeking individuals have a higher propensity for engaging in political violence. It also found that providing access to a more peaceful, yet still exciting political group helps reduce this effect.

While the experimental method can be a valuable tool for learning more about psychology and its impacts, it also comes with a few pitfalls.

Experiments may produce artificial results, which are difficult to apply to real-world situations. Similarly, researcher bias can impact the data collected. Results may not be able to be reproduced, meaning the results have low reliability .

Since humans are unpredictable and their behavior can be subjective, it can be hard to measure responses in an experiment. In addition, political pressure may alter the results. The subjects may not be a good representation of the population, or groups used may not be comparable.

And finally, since researchers are human too, results may be degraded due to human error.

What This Means For You

Every psychological research method has its pros and cons. The experimental method can help establish cause and effect, and it's also beneficial when research funds are limited or time is of the essence.

At the same time, it's essential to be aware of this method's pitfalls, such as how biases can affect the results or the potential for low reliability. Keeping these in mind can help you review and assess research studies more accurately, giving you a better idea of whether the results can be trusted or have limitations.

Colorado State University. Experimental and quasi-experimental research .

American Psychological Association. Experimental psychology studies human and animals .

Mayrhofer R, Kuhbandner C, Lindner C. The practice of experimental psychology: An inevitably postmodern endeavor . Front Psychol . 2021;11:612805. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.612805

Mandler G. A History of Modern Experimental Psychology .

Stanford University. Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt . Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Britannica. Gustav Fechner .

Britannica. Hermann von Helmholtz .

Meyer A, Hackert B, Weger U. Franz Brentano and the beginning of experimental psychology: implications for the study of psychological phenomena today . Psychol Res . 2018;82:245-254. doi:10.1007/s00426-016-0825-7

Britannica. Georg Elias Müller .

McCambridge J, de Bruin M, Witton J. The effects of demand characteristics on research participant behaviours in non-laboratory settings: A systematic review . PLoS ONE . 2012;7(6):e39116. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039116

Laboratory experiments . In: The Sage Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Allen M, ed. SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781483381411.n287

Schweizer M, Braun B, Milstone A. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship — quasi-experimental designs . Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 2016;37(10):1135-1140. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.117

Glass A, Kang M. Dividing attention in the classroom reduces exam performance . Educ Psychol . 2019;39(3):395-408. doi:10.1080/01443410.2018.1489046

Keskin M, Ooms K, Dogru AO, De Maeyer P. Exploring the cognitive load of expert and novice map users using EEG and eye tracking . ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf . 2020;9(7):429. doi:10.3390.ijgi9070429

Ho A, Hancock J, Miner A. Psychological, relational, and emotional effects of self-disclosure after conversations with a chatbot . J Commun . 2018;68(4):712-733. doi:10.1093/joc/jqy026

Haynes IV J, Frith E, Sng E, Loprinzi P. Experimental effects of acute exercise on episodic memory function: Considerations for the timing of exercise . Psychol Rep . 2018;122(5):1744-1754. doi:10.1177/0033294118786688

Torresin S, Pernigotto G, Cappelletti F, Gasparella A. Combined effects of environmental factors on human perception and objective performance: A review of experimental laboratory works . Indoor Air . 2018;28(4):525-538. doi:10.1111/ina.12457

Schumpe BM, Belanger JJ, Moyano M, Nisa CF. The role of sensation seeking in political violence: An extension of the significance quest theory . J Personal Social Psychol . 2020;118(4):743-761. doi:10.1037/pspp0000223

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Best-Selling Books

- Zimbardo Research Fields

The Stanford Prison Experiment

- Heroic Imagination Project (HIP)

- The Shyness Clinic

The Lucifer Effect

Time perspective theory, books by psychologists.

- Famous Psychologists

- Psychology Definitions

Psychology Experiment: Psychology Definition, History & Examples

Psychology experiments are foundational to the empirical study of human behavior and mental processes. Rooted in rigorous scientific methodology, these experiments aim to test hypotheses and expand our understanding of psychological phenomena.

The history of psychological experimentation dates back to the late 19th century, with the establishment of the first psychological laboratory by Wilhelm Wundt in 1879, marking the formal genesis of psychology as a distinct scientific field. Over the years, seminal experiments such as the Pavlov’s conditioning , Milgram’s obedience study, and the Stanford Prison Experiment have significantly influenced the discipline .

This overview will elucidate the definition of psychology experiments, trace their historical development, and present examples that highlight their role in advancing psychological research, while also delineating key terms and referencing pivotal academic contributions.

Table of Contents

A psychology experiment is a research method where researchers manipulate variables to see how they affect people’s behavior or thoughts.

It helps scientists understand cause and effect relationships and uses statistical analysis to determine the significance of findings.

Psychology as a scientific discipline has its roots in the late 19th century when it emerged as a distinct field of study. The term ‘psychology’ originated from the Greek words ‘psyche’ meaning ‘soul’ or ‘mind’ and ‘logos’ meaning ‘study’ or ‘knowledge.’ It can be traced back to ancient civilizations such as ancient Egypt, Greece, China, and India, where philosophers and scholars contemplated the nature of the mind and human behavior.

However, the development of psychology as an empirical science began in the late 19th century. One of the key figures associated with its establishment was Wilhelm Wundt, a German psychologist who is often referred to as the ‘father of experimental psychology.’ In 1879, Wundt founded the first psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig in Germany. This marked a significant turning point in the field, as it shifted from philosophical speculation to experimental inquiry.

Wundt’s laboratory focused on studying consciousness and the structure of the mind. He developed methodologies such as introspection, where participants were asked to reflect on their own conscious experiences and describe their thoughts and sensations. Wundt also conducted reaction time experiments to understand the time it takes for individuals to respond to certain stimuli. These experimental protocols laid the foundation for future psychological research and shaped the direction of the field.

The early 20th century witnessed the diversification of psychology into different schools of thought, each with its own set of theories and methodologies. One notable school was behaviorism , led by figures such as John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner. Behaviorists believed that behavior could be understood and predicted by studying observable stimuli and responses. They conducted experiments using animals and humans to examine the effects of rewards and punishments on behavior.

Another influential school was cognitivism, which gained prominence in the mid-20th century. Key figures in this movement included Ulric Neisser and Jean Piaget. Cognitivists focused on studying mental processes such as perception , memory , and problem-solving. They used experimental methods to investigate how individuals acquire, process, and store information.

Psychoanalysis, developed by Sigmund Freud, also made significant contributions to the field of psychology. Freud’s theories focused on the unconscious mind and the influence of early childhood experiences on behavior. Although psychoanalysis relied less on traditional experimental methods, it emphasized the importance of clinical observation and case studies.

Throughout its history, psychology has been shaped by significant events and studies that have contributed to its evolution. For example, the Stanford Prison Experiment conducted by Philip Zimbardo in 1971 shed light on the powerful influence of situational factors on human behavior. This study demonstrated the potential for individuals to adopt abusive roles and highlighted ethical concerns in psychological research.

Practical Examples of Psychology Terms in Real-Life Contexts:

- Confirmation Bias: Imagine you have a friend who strongly believes in conspiracy theories. Whenever they come across new information, they tend to selectively focus on evidence that supports their preexisting beliefs, while dismissing anything that contradicts them. This is an example of confirmation bias, where our tendency to seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs can influence our decision-making and perception of reality.

- Cognitive Dissonance: Picture a person who is trying to quit smoking. They know that smoking is harmful to their health , but they still find it difficult to give up the habit. This creates a state of cognitive dissonance, where there is a conflict between their knowledge of the negative effects of smoking and their desire to continue the behavior. They may try to resolve this dissonance by rationalizing their smoking or finding reasons to justify their actions.

- Halo Effect: Consider a job interview scenario. The interviewer meets a candidate who is well-dressed, confident, and articulate. Based on these initial positive impressions, the interviewer may unconsciously assume that the candidate possesses other desirable qualities, such as intelligence or competence. This is an example of the halo effect, where our overall positive impression of someone influences our perception of their specific traits or abilities.

- Learned Helplessness: Imagine a student who consistently receives negative feedback and criticism from their teacher, regardless of their effort or performance . Over time, the student may start to believe that their efforts are futile and that they have no control over their academic success. This learned helplessness can lead to a decrease in motivation and a belief that they are incapable of improving, even when opportunities for success arise.

- Self-fulfilling Prophecy: Think of a situation where a person believes they are bad at public speaking. Due to this belief, they may feel anxious and lack confidence when presenting in front of others. As a result, their performance may suffer, confirming their initial belief that they are indeed bad at public speaking. This is an example of a self-fulfilling prophecy, where our beliefs about ourselves or others can influence our behavior in a way that aligns with those beliefs, ultimately shaping the outcome.

Related Terms

Psychology’s rich lexicon includes terms that illuminate various aspects of human behavior and mental processes, each interwoven with the field’s history and practice. To fully grasp psychological experimentation, one must understand related terminology.

For example, in addition to the concept of a ‘variable’ denoting anything that can vary and potentially impact experimental outcomes, there are other closely linked terms such as ‘independent variable’ and ‘dependent variable .’

The independent variable is the factor that the researcher manipulates or controls in an experiment to observe its effect on the dependent variable. In contrast, the dependent variable is the outcome or behavior that is measured and is expected to change as a result of the manipulation of the independent variable. These two terms work together to establish cause-and-effect relationships in experimental research.

Furthermore, the ‘control group’ is another related term that complements the concept of a variable. While a variable can be any factor that can vary, a control group refers to participants who are not exposed to the experimental treatment. By comparing the outcomes of the control group to those of the experimental group, researchers can determine the effectiveness or impact of the independent variable.

Another important term closely associated with variables and control groups is ‘random assignment.’ This term refers to the process of randomly assigning participants to different experimental conditions. Random assignment ensures that each subject has an equal chance of being placed in any group, thus mitigating selection biases. It helps create groups that are comparable and reduces the likelihood that any pre-existing differences among participants will confound the results.

Lastly, ‘double-blind’ procedures are crucial in preserving the integrity of results by preventing expectancy effects. In a double-blind study, neither the participants nor the experimenters know who is receiving a particular treatment. This helps eliminate biases and unconscious influences that could affect the results. By keeping both parties unaware, the researchers can obtain more objective and reliable data.

Mastery of these terms, including variables, independent and dependent variables, control groups, random assignment, and double-blind procedures, is essential for methodical analysis within psychological research. Understanding their relationships and how they differ or complement each other is crucial for designing and interpreting experiments accurately.

Building upon the foundational terms outlined above, this section will provide a selection of key references that have contributed to the understanding and methodology of psychological experimentation. Notably, B.F. Skinner’s work on operant conditioning revolutionized behavioral psychology through empirical research, as documented in his seminal book, ‘The Behavior of Organisms’ (Skinner, 1938). Skinner’s research demonstrated the principles of reinforcement and punishment, which have had a profound impact on the field of psychology.

Another influential study in the field of psychology is the ‘Stanford prison experiment’ conducted by Zimbardo (1971). This study explored the effects of perceived power and social roles on behavior within a simulated prison environment . The ethical considerations raised by this experiment have since helped shape the guidelines for conducting psychological research involving human participants.

In the realm of cognitive psychology, Miller’s publication ‘The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two’ (Miller, 1956) provided valuable insights into the limitations of human memory. The study demonstrated that the average person’s short-term memory has a limited capacity, with an optimal range of around seven items. This research has influenced subsequent studies on memory and cognition .

These references, along with many others, have played significant roles in advancing the field of psychology. They are academically credible sources that provide a foundation for further reading and understanding of the term being discussed.

References:

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behavior of Organisms. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1971). The Stanford prison experiment. Stanford University.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97.

Related posts:

No related posts.

RECOMMENDED POSTS

A comprehensive guide to books by carol ryff, a comprehensive guide to books by clark l. hull, a comprehensive guide to books by karen horney, a comprehensive guide to books by viktor frankl, a comprehensive guide to books by stanley milgram, notable psychologists, life and legacy of psychologist albert bandura, life and legacy of psychologist howard gardner, life and legacy of psychologist carol ryff, life and legacy of psychologist j.p. guilford, life and legacy of psychologist douglas mcgregor, featured psychology definitions, behavior feedback effect: psychology definition, history & examples, effortful processing: psychology definition, history & examples, feature detectors: psychology definition, history & examples, interposition: psychology definition, history & examples, irreversibility: psychology definition, history & examples, mirror image perceptions: psychology definition, history & examples, place theory: psychology definition, history & examples, relative clarity: psychology definition, history & examples, sequential processing: psychology definition, history & examples, splanchnophilia: psychology definition, history & examples.

- Stay Connected

- Terms Of Use

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Natural Experiment. A natural experiment in psychology is a research method in which the experimenter observes the effects of a naturally occurring event or situation on the dependent variable without manipulating any variables. Natural experiments are conducted in the day (i.e., real life) environment of the participants, but here, the ...

Definition: Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on conducting systematic and controlled experiments to study human behavior and cognition. Overview: Experimental psychology aims to gather empirical evidence and explore cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

The Building Blocks: Key Elements of Psychological Experiments. Let's dive deeper into the nuts and bolts of psychological experiments. At the heart of every experiment are two star players: the independent and dependent variables. The independent variable is the factor that researchers manipulate or change.

An experiment involves the manipulation of an independent variable, the measurement of a dependent variable, and the exposure of various participants to one or more of the conditions being studied. Random selection of participants and their random assignment to conditions also are necessary in experiments. —experimental adj.

Psychological experiments often walk a fine line between scientific inquiry and ethical considerations. After all, we're dealing with human participants, not lab rats. First and foremost, there's informed consent. This is the golden rule of psychological research. ... Histogram in Psychology: Definition, Applications, and Significance

The famous "split-brain" experiments, for instance, revealed fascinating insights into how the two hemispheres of the brain work together. These examples barely scratch the surface of the diverse and exciting world of psychological experiments. Each study contributes to our growing understanding of the human mind and behavior, piece by piece.

Experimental psychology refers to work done by those who apply experimental methods to psychological study and the underlying processes. Experimental psychologists employ human participants and animal subjects to study a great many topics, including (among others) sensation, perception, memory, cognition, learning, motivation, emotion; developmental processes, social psychology, and the neural ...

Learn more about methods for experiments in psychology. ... Results may not be able to be reproduced, meaning the results have low reliability. Since humans are unpredictable and their behavior can be subjective, it can be hard to measure responses in an experiment. In addition, political pressure may alter the results. The subjects may not be ...

Psychology experiments are foundational to the empirical study of human behavior and mental processes. Rooted in rigorous scientific methodology, these experiments aim to test hypotheses and expand our understanding of psychological phenomena. The history of psychological experimentation dates back to the late 19th century, with the establishment of the first psychological laboratory by ...

experimental psychology, a method of studying psychological phenomena and processes.The experimental method in psychology attempts to account for the activities of animals (including humans) and the functional organization of mental processes by manipulating variables that may give rise to behaviour; it is primarily concerned with discovering laws that describe manipulable relationships.