Advertisement

Impact of online learning on student's performance and engagement: a systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 01 November 2024

- Volume 3 , article number 205 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Catherine Nabiem Akpen ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-2218-2254 1 ,

- Stephen Asaolu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7116-6468 1 ,

- Sunday Atobatele ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1947-2561 2 ,

- Hilary Okagbue ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3779-9763 1 &

- Sidney Sampson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5303-5475 2

9222 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The rapid shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly influenced educational practices worldwide and increased the use of online learning platforms. This systematic review examines the impact of online learning on student engagement and performance, providing a comprehensive analysis of existing studies. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline, a thorough literature search was conducted across different databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR for articles published between 2019 and 2024. The review included peer-reviewed studies that assess student engagement and performance in online learning environments. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 18 studies were selected for detailed analysis. The analysis revealed varied impacts of online learning on student performance and engagement. Some studies reported improved academic performance due to the flexibility and accessibility of online learning, enabling students to learn at their own pace. However, other studies highlighted challenges such as decreased engagement and isolation, and reduced interaction with instructors and peers. The effectiveness of online learning was found to be influenced by factors such as the quality of digital tools, good internet, and student motivation. Maintaining student engagement remains a challenge, effective strategies to improve student engagement such as interactive elements, like discussion forums and multimedia resources, alongside adequate instructor-student interactions, were critical in improving both engagement and performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the Factors Affecting Student Academic Performance in Online Programs: A Literature Review

A meta-analysis addressing the relationship between self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance in online higher education

Online engagement and performance on formative assessments mediate the relationship between attendance and course performance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Online learning also referred to as E-learning or remote learning is essentially a web-based program that gives learners access to knowledge or information whenever needed, regardless of their proximity to a location or time constraints [ 1 ]. This form of learning has been around for a while, it started in the late 1990s and it has advanced quickly. It has been considered a good choice, particularly for adult learners [ 2 ].

Online education promotes a student-centred approach, whereby students are expected to actively participate in the learning process. The digital tools used in online learning include interactive elements, computers, mobile devices, the internet, and other devices that allow students to receive and share knowledge [ 3 ]. Different types of online learning exist, such as microlearning, individualized learning, synchronous, asynchronous, blended, and massive open online courses [ 2 ]. Online learning offers several advantages to students, such as its adaptability to individual needs, ease, and flexibility in terms of involvement. With user-friendly online learning applications on their personal computers (PCs) or laptops, students can take part in their online courses from any convenient place, they can take specific courses with less time and location restrictions [ 4 ].

Learning experiences and academic success of students are some of the difficulties of online education [ 5 ]. Furthermore, while technology facilitates accessibility and ease of use of online learning platforms, it can also have restrictive effects, where many students struggle to gain internet access [ 6 ], in turn causes problems with participation and attendance in virtual classes, which makes it difficult to adopt online learning platforms [ 7 ]. Other issues with e-learning include educational policy, learning pedagogy, accessibility, affordability, and flexibility [ 8 ]. Many developing countries have substantial issues with reliable internet connection and access to digital devices, especially among economically backward children [ 9 ]. Maintaining student engagement in an online classroom can be more difficult than in a traditional face-to-face setting [ 10 ]. Even with all the advantages of online learning, there is reduced interaction between students and course facilitators. Another barrier to online learning is the lack of opportunities for human connection, which was thought to be essential for creating peer support and creating in-depth group discussions on the subject [ 11 ].

Over the past four years, COVID-19 has spread over the world, forcing schools to close, hence the pandemic compelled educators and learners at every level to swiftly adapt to online learning to curb the spread of the disease while ensuring continuous education [ 12 ]. The emergence of the pandemic rendered traditional face-to-face teaching and training methods unfeasible [ 13 ]. Some studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 ] acknowledged that the move to online learning was significant and sudden, but that it was also necessary to continue the learning process. This abrupt change sparked an argument regarding the standard of learning and satisfaction with learning among students [ 17 ].

While there are similarities between face-to-face (F2F) and online learning, they still differ in several ways [ 18 ], some of the similarities are: prerequisites for students include attendance, comprehension of the subject matter, turning in homework, and completion of group projects. The teachers still need to create curricula, enhance the quality of their instruction, respond to inquiries from students, inspire them to learn, and grade assignments [ 19 ]. One difference between online learning and F2F learning is the fact that online learning is student-centred and necessitates active learning while F2F learning is teacher-centred and demands passive learning from the student [ 19 ]. Another difference is teaching and learning has to happen at the same time and location in face-to-face learning, while online learning is not restricted by time or location [ 20 ]. Online learning allows teaching and learning to be done separately using internet-based information delivery systems [ 21 ].

Finding more efficient strategies to increase student engagement in online learning settings is necessary, as the absence of F2F interactions between students and instructors or among students continues to be a significant issue with online learning [ 20 ]. Student engagement has been defined as how involved or interested students appear to be in their learning and how connected they are to their classes, their institutions, and each other [ 22 ]. Engagement has been pointed out as a major dimension of students’ level and quality of learning, and is associated with improvement in their academic achievement, their persistence versus dropout, as well as their personal and cognitive development [ 23 ]. In an online setting, student engagement is equally crucial to their success and performance [ 24 ].

Change in learning delivery method is accompanied by inquiries when assessing whether online education is a practical replacement for traditional classroom instruction, cost–benefit evaluation, student experience, and student achievement are now being carefully considered [ 19 ]. This decision-making process will most likely continue if students seek greater learning opportunities and technological advances [ 19 ].

An individual's academic performance is significant to their success during their time in an educational institution [ 25 ], students' academic achievement is one indicator of their educational accomplishment. However, it is frequently seen that while student learning capacities are average, the demands placed on them for academic achievement are rising. This is the reason why the student's academic performance success rate is below par [ 25 ].

Numerous authors [ 11 , 13 , 18 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ] have examined how students and teachers view online learning, but it is still important to understand how much students are learning from these platforms. After all, student performance determines whether a subject or course is successful or unsuccessful.

The increase in the use of online learning calls for a careful analysis of its impact on student performance and engagement. Investigating the online learning experiences of students will guide education policymakers such as ministries, departments, and agencies in both the public and private sectors in the evaluation of the potential pros and cons of adopting online education against F2F education [ 30 ]

Given the foregoing, this study was carried out to; (1) investigate the online learning experiences of students, (2) review the academic performance of students using online learning platforms, and (3) explore the levels of students’ engagement when learning using online platforms.

2 Methodology

The study was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [ 31 ].

2.1 Search strategy and databases used

PubMed, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR were databases used to search for articles using identified search terms. The three data bases were selected for their extensive coverage of health sciences, social sciences and educational articles. The articles searched were between the years 2019–2024, this is because online learning became popular during the COVID-19 pandemic which started in 2019. Only English, open-access, and free full-text articles were selected for review, this is to ensure that the data analysed are publicly available to ascertain transparency and reproducibility of the review. The search was carried out in February 2024. The search strategy terms used are shown in Table 1 .

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles included for review were studies conducted on students enrolled in any field in a higher institution. Only articles in English language that were published between 2019 and 2024 which assessed student performance and engagement were included.

Articles excluded are studies involving pupils (students in primary school), articles not written in English language, and those published before 2019. Also, studies that did not follow the declaration of Helsinki on research ethics and without clear evidence of ethical consideration and approval were excluded.

2.3 Search outcomes

A total of 1078 articles were obtained from the databases searched. Four articles were duplicated and eliminated from the review. After the elimination of duplicates, titles, and abstracts were used to evaluate the remaining 1074 articles. These articles were screened based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 1052 studies were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts. Complete texts of 22 articles were read and four were found to be irrelevant to the review, a total of 18 articles were used for the systematic review.

The PRISMA flowchart shown in Fig. 1 illustrates the procedure used to screen and assess the articles.

A PRISMA flow chart of studies included in the systematic review

2.4 Data analysis

A data synthesis table was developed to collect relevant information on the author, year study was conducted, study design, study location, sample methodology, sample size, population, assessment tool, findings on student performance and student engagement, other findings, and limitations. Data was collected about whether students’ performance and engagement improved or declined following the introduction of online learning in their education. Data about the extent of the improvement or decline was also collected.

2.5 Quality appraisal

A quality assessment was carried out using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) developed to appraise systematic reviews. The checklist was used to analyse the included articles.

The characteristics of the 18 articles included in the study are presented in Table 2 . Ten (55.6%) were cross-sectional studies [ 2 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ], three (16.7%) were mixed methods studies [ 18 , 26 , 37 ], two (11.1%) were quasi-experimental and longitudinal studies [ 3 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], and one (5.5%) was a qualitative study [ 41 ].

The population involved in the study was a mix of students from various fields and departments, including medical, nursing, pharmacy, psychology, students taking management courses, and engineering students [ 3 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 38 , 39 , 41 ]. Other students were undergraduates from different fields that were not mentioned [ 2 , 10 , 26 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 ].

Study outcomes were categorized using three categories; student performance, student engagement, and studies that measured both student performance and engagement.

The summary of findings from the included studies are presented in Table 3 . Questionnaire surveys were mostly used across all the studies, however, one study used focus group discussions [ 41 ] and another study used a checklist to collect administrative data from student registers [ 40 ]. Study designs used in the included studies are cross-sectional, mixed methods, quasi-experimental, qualitative, and longitudinal. Studies were included from various countries across all six continents, countries in Asia constituted most of the studies (n = 7), Europe (n = 5), North America (n = 2), South America, Africa, and Australia all had one country represented in the study location.

3.1 Students’ performance

The impact of online learning on student performance was documented in thirteen studies [ 3 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. In the study conducted by Elnour et al. [ 12 ], about half of the respondents strongly agreed that online learning had a negative impact on their grades in comparison to when they were attending face-to-face classes, two other studies had similar findings where students reported a decline in their grades during online learning [ 34 , 40 ].

Two studies experimented to compare grades achieved by students taking online classes (experimental group) with students taking face-to-face classes (control group) and found that those in the experimental group scored higher during examinations than those in the control group [ 38 , 39 ]. Nine studies included in this review showed a positive impact of online learning on student performance [ 3 , 10 , 13 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 ] students reported getting higher scores during examinations when they switched to online learning.

Two studies measured the performance of students before online learning and during online learning [ 3 , 40 ]. Both studies had varying findings, one of the studies found that when students started learning online, their grades improved on average from 4.7/10 to 5.15/10 and dropped to 4.6/10 when they went back to face-to-face learning [ 3 ], while another study used students' registers to capture their grades before online learning and when they started studying online and found that the switch to online learning led to a lesser number of credits obtained by the students [ 40 ].

3.2 Students’ engagement

Student engagement during online learning was reported in ten of the reviewed articles [ 2 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 41 ]. Students reported the negative effect of online learning on engagement with their peers and teachers. Nonetheless, in one of the studies [ 18 ], the respondents reported that online learning did not affect engagement with their lecturers, even though they felt least engaged with their peers. Students reported the effect of isolation when they were studying and taking classes online in comparison to when they had face-to-face learning [ 2 , 41 ], they revealed that the abrupt switch did not allow them to understand and adapt to the new form of learning and it led to feelings of isolation and separation from their classmates and teachers [ 2 ]

For science-based courses, students reported concern about carrying out practical classes, as studying online did not grant them the opportunity to effectively carry out practical [ 18 ]. Also, medical students reported dissatisfaction in interacting with their patients, which led to less engagement and connection [ 13 ]. One of the studies reviewed stated the role of engagement in increasing student performance over time, students stated that when they interact and engage with their teams and lecturers, they tend to perform better in their examinations [ 18 ].

4 Discussion

This study aimed to examine the impact of online learning on students' academic performance and engagement. The results underscore the varied impacts of online learning on student performance and engagement. While some students benefited from the flexibility and new opportunities presented by online learning, others struggled with the lack of direct interaction and practical engagement. This suggests that while online learning has potential, it requires careful implementation and support to address the challenges of engagement and practical application, particularly in fields requiring hands-on experience.

Majority of the articles in this review showed that online learning did not negatively affect the academic performance of students, though the studies did not have a standardized method of measuring their performance before online learning and during studying online, most of the survey was based on the students' perceptions. These findings support the findings of other studies that reported an increase in students' grades when they studied online [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Possible reasons highlighted for the increase in performance include the availability of recorded videos; students were able to study and listen to past teachings at their own pace and review course content when necessary. This enabled them to manage their time better and strengthen their understanding of complex materials and courses. Also, the use of computers and the availability of good internet connectivity were major reasons emphasized by students in helping them achieve good grades. The incorporation of digital tools like interactive quizzes, recorded videos, and learning management systems (LMS) provided students an interesting avenue to learn, which enhanced their academic performance [ 45 ]. Many students found that independent learning was suitable and matched their unique learning style better than F2F learning, this could be another reason for the improvement in their grades.

Despite reporting good grades with online learning, students still felt unsatisfied with this mode of learning, they reported bad internet connectivity, especially in studies conducted in Africa and Asia [ 1 , 13 ]. Furthermore, there were no academic performance variations between rural and urban learners [ 46 ], this finding varied with the finding of Bacher et al. [ 47 ] who stated that students in rural communities will require more support to bridge the academic gap experienced with their peers who live in urban settings. Another author compared the impact of environmental conditions at home and student academic performance, and it was found that students who had poor lighting conditions or those who were exposed to noisy environments performed poorly, this suggests that online learners need proper indoor lighting, ventilation, and a quiet environment for proper learning [ 42 ]

However, one of the studies found that online learning reduced the academic grades of the students, this could be because of the use of smartphones in carrying out examinations instead of using computers, and inexperience with the use of the Learning Management System (LMS) [ 34 ].

A lot of implications can arise as a result of improved performance among students due to a shift from F2F to online learning platforms. For students, it can increase confidence and contentment [ 48 ], but because of the dependence on technology, students also need to learn time management skills and self-discipline [ 49 ] which are essential for success in an online environment. Families may feel less stressed about their children’s academic success, but this might also result in more pressure to sustain these outcomes [ 50 ], particularly if the progress is linked directly to online learning. More educated citizens will benefit from increased academic performance through an increase in rates of employment and economic growth [ 51 ], but unequal access to technology could make the divide between various socioeconomic classes more pronounced. Furthermore, improved student performance has the potential to elevate the overall quality of the workforce, accelerating economic growth and competitiveness in the global market [ 52 ]. However, disparities in online learning must be addressed to guarantee that every student has an equal chance of success.

In terms of student engagement, similar findings were seen across the reviewed articles, most students reported that online learning was less engaging, and they could not associate with their peers or lecturers which made them feel self-isolated. This finding has been supported by Hollister et al. [ 43 ] where students complained of less engagement in online classes despite attaining good grades, they missed the spontaneous conversations and collaborations that are typical in a classroom setting. Motivation is an important element in both online and offline learning, students need self-motivation for overall learning outcomes [ 44 ]. Findings from this review indicate that students who reported being able to engage with their teams and lecturers actively attribute their success to self-motivation. Also, Cents-Boonstra et al. [ 53 ] investigated the role of motivating teaching behaviour and found that teachers who offered support and guidance during learning had more student engagement in comparison to teachers who did not offer any support or show enthusiasm for teaching. Courses that previously required hands-on experiences, like clinical practice or laboratory work, was challenging to conduct online, medical students expressed dissatisfaction with not being able to conduct practical sessions in the laboratory or interact effectively with their patients, this made learning online an isolating experience. Their participation dropped as a result of the separation between the theoretical and practical components of their education. This supports the finding of Khalil et al. [ 54 ] where medical students stated that they missed having live clinical sessions and couldn’t wait to go back to having a F2F class. Major barriers to participation included a lack of personal devices, and, inconsistent internet access, especially in rural or low-income areas. These barriers made it difficult for students to participate fully in online classes and also made them feel more frustrated and disengaged. This is similar to a study by Al-Amin et al. [ 11 ] where tertiary students studying online complained of less engagement in classroom activities.

Generally, students reported a negative effect of online learning on their engagement. This could be a result of poor technology skills, unavailability of personal computers or smartphones, or lack of internet services [ 55 ].

In a study conducted by Heilporn et al. [ 56 ], the author examined strategies that can be used by teachers to improve student engagement in a blended learning environment. Presenting a clear course structure and working at a particular pace, engaging learners with interactive activities, and providing additional support and constant feedback will help in improving overall student engagement. In a study by Gopal et al. [ 57 ], it was found that quality of instructor and the ability to use technological tools is an important element in influencing students engagement. The instructor needs to understand the psychology of the students in order to effectively present the course material.

A decrease in student engagement can have a detrimental effect on their entire educational experience, this can affect motivation and satisfaction. In the long-term, this could lead to decreased academic achievement and increased dropout rates [ 58 ]. To maintain students' motivation and engagement, families might need to put in extra effort especially if they simultaneously manage the online learning needs of numerous children [ 59 ]. This can result in additional stress or financial constraints in purchasing technological tools. In addition, for students studying online, it results in a less unified learning environment, which may diminish community bonds, and instructors will find it difficult to assist disengaged and potentially falling behind students [ 60 ].

The contrast between positive student performance and negative student engagement suggests that while online learning is a useful approach, it is less successful at fostering the interactive and social aspects of education. Online learning must include interactive components like discussion boards, and group projects that will enable in-person communication [ 61 ]. Furthermore, it is essential to guarantee that students have access to sufficient technology tools and training to enable them participate fully.

Some learners found it difficult to give the benefits of learning online, but none failed to give the benefits of face-to-face learning. In a study by Aguilera-Hermida [ 6 ], college students preferred studying in a physical classroom against studying online, they also found it hard to adapt to online classes, this decreased their level of participation and engagement. Also, an increase in good grades might be a result of cheating behaviours [ 3 ], given that unlike face-to-face learning where teachers are present to invigilate and validate that examinations were individual-based, for online learning it is difficult to determine if examinations were truly carried out by the students, giving students the option to share their answers with classmates or obtain them from internet resources. The studies did not state if measures were put in place to ensure exams taken online were devoid of cheating by the students.

Furthermore, online learning is here to stay, but there is a need for planning and execution of the process to mitigate the issue of students engaging effectively. Ignorance of this could put the possible advantages of this process in danger [ 62 ].

4.1 Limitations

A major limitation of this systematic review is the paucity of studies that objectively measured performance and engagement in students before and after the introduction of online learning. Findings in fourteen (78%) of the included articles were self-reported by the students which could lead to recall and/or desirability bias. In addition, the lack of uniform measurement or scale for assessing students’ performance and engagement is also a limitation. Subsequently, we suggest that standardized study tools should be developed and validated across various populations to more accurately and objectively evaluate the impact of the introduction of online learning on students’ performance and engagement. More studies should be conducted with clear pre- and post-intervention measurements using different pedagogical approaches to access their effects on students’ performance and engagement. These studies should also design ways of measuring indicators objectively without recall or desirability biases. Furthermore, the exclusion of studies that are not open access as well as publication bias for articles not published in English language are also limitations of this study.

5 Conclusion

The switch to online learning had both its advantages and disadvantages. The flexibility and accessibility of online platforms have played a major role in the enhancement of student performance, yet the decline in engagement underscores the need for more efficacious strategies to promote engagement. Online learning had a positive impact on student performance, most of the students reported either an increase or no change in grades when they changed to learning online. Only three studies stated a decline in student performance. Overall, students felt with online learning, they could not engage with their peers, teams, and teachers. They had a feeling of social isolation and felt more engagement would have improved their performance better. Schools and policymakers must develop strategies to mitigate the challenge of student engagement in online learning. This is necessary to prepare institutions for potential future pandemics which will compel reliance on online learning, this is critical for maintaining student satisfaction and overall learning outcomes.

In summary, online learning has the capacity to enhance academic achievement, but its effectiveness depends on effectively resolving the barriers associated with student involvement. Future studies should examine the long-term effects of online learning on student's performance and engagement with emphasis on creating strategies to improve the social and interactive components of the learning process. This is essential to guarantee that, in the future, online learning will be a viable and productive educational medium not just a band-aid fix during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The articles used for this systematic review are all cited and publicly available.

Bossman A, Agyei SK. Technology and instructor dimensions, e-learning satisfaction, and academic performance of distance students in Ghana. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):09200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E09200 .

Article Google Scholar

Rahman A, Islam MS, Ahmed NAMF, Islam MM. Students’ perceptions of online learning in higher secondary education in Bangladesh during COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Human Open. 2023;8(1):100646. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2023.100646 .

Pérez MA, Tiemann P, Urrejola-Contreras GP. The impact of the learning environment sudden shifts on students’ performance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ Méd. 2023;24(3):100801. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EDUMED.2023.100801 .

Basar ZM, Mansor AN, Jamaludin KA, Alias BS. The effectiveness and challenges of online learning for secondary school students—a case study. Asian J Univ Educ. 2021;17(3):119–29.

Rajabalee YB, Santally MI. Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2021;26(3):2623–56.

Aguilera-Hermida AP. College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. Int J Educ Res Open. 2020;1:100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011 .

Nambiar D. The impact of online learning during COVID-19: students’ and teachers’ perspective. Int J Indian Psychol. 2020;8(2):783–93.

Google Scholar

Maheshwari M, Gupta AK, Goyal S. Transformation in higher education through e-learning: a shifting paradigm. Pac Bus Rev Int. 2021;13(8):49–63.

Pokhrel S, Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High Educ Future. 2021;8(1):133–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631120983481 .

Kedia P, Mishra L. Exploring the factors influencing the effectiveness of online learning: a study on college students. Soc Sci Human Open. 2023;8(1):100559. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2023.100559 .

Al-Amin M, Al Zubayer A, Deb B, Hasan M. Status of tertiary level online class in Bangladesh: students’ response on preparedness, participation and classroom activities. Heliyon. 2021;7(1):e05943. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2021.E05943 .

Elnour AA, Abou Hajal A, Goaddar R, Elsharkawy N, Mousa S, Dabbagh N, Mohamad Al Qahtani M, Al Balooshi S, Othman Al Damook N, Sadeq A. Exploring the pharmacy students’ perspectives on off-campus online learning experiences amid COVID-19 crises: a cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(7):1339–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.05.024 .

Fahim A, Rana S, Haider I, Jalil V, Atif S, Shakeel S, Sethi A. From text to e-text: perceptions of medical, dental and allied students about e-learning. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12157. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E12157 .

Henriksen D, Creely E, Henderson M. Folk pedagogies for teacher transitions: approaches to synchronous online learning in the wake of COVID-19. J Technol Teach Educ. 2020;28(2):201–9.

Zhu X, Chen B, Avadhanam RM, Shui H, Zhang RZ. Reading and connecting: using social annotation in online classes. Inf Learn Sci. 2020;121(5/6):261–71.

Bao W. COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: a case study of Peking University. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2020;2(2):113–5.

Baber H. Determinants of students’ perceived learning outcome and satisfaction in online learning during the pandemic of COVID-19. J Educ Elearn Res. 2020;7(3):285–92.

Afzal F, Crawford L. Student’s perception of engagement in online project management education and its impact on performance: the mediating role of self-motivation. Proj Leadersh Soc. 2022;3:100057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2022.100057 .

Paul J, Jefferson F. A comparative analysis of student performance in an online vs. face-to-face environmental science course from 2009 to 2016. Front Comput Sci. 2019;1:7.

Francescucci A, Rohani L. Exclusively synchronous online (VIRI) learning: the impact on student performance and engagement outcomes. J Mark Educ. 2019;41(1):60–9.

Pei L, Wu H. Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1666538.

Thang SM, Mahmud N, Mohd Jaafar N, Ng LLS, Abdul Aziz NB. Online learning engagement among Malaysian primary school students during the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Innov Creat Change. 2022;16(2):302–26.

Ribeiro L, Rosário P, Núñez JC, Gaeta M, Fuentes S. “First-year students background and academic achievement: the mediating role of student engagement. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2669.

Muzammil M, Sutawijaya A, Harsasi M. Investigating student satisfaction in online learning: the role of student interaction and engagement in distance learning university. Turk Online J Distance Educ. 2020;21(Special Issue-IODL):88–96.

Mandasari B. The impact of online learning toward students’ academic performance on business correspondence course. EDUTEC. 2020;4(1):98–110.

Chen LH. Moving forward: international students’ perspectives of online learning experience during the pandemic. Int J Educ Res Open. 2023;5:100276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2023.100276 .

Wu YH, Chiang CP. Online or physical class for histology course: Which one is better? J Dent Sci. 2023;18(3):1295–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2023.03.004 .

Salahshouri A, Eslami K, Boostani H, Zahiri M, Jahani S, Arjmand R, Heydarabadi AB, Dehaghi BF. The university students’ viewpoints on e-learning system during COVID-19 pandemic: the case of Iran. Heliyon. 2022;8(2):e08984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08984 .

Maqbool S, Farhan M, Abu Safian H, Zulqarnain I, Asif H, Noor Z, Yavari M, Saeed S, Abbas K, Basit J, Ur Rehman ME. Student’s perception of E-learning during COVID-19 pandemic and its positive and negative learning outcomes among medical students: a country-wise study conducted in Pakistan and Iran. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;82:104713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104713 .

Anderson T. Theories for learning with emerging technologies. In: Veletsianos G, editor. Emerging technologies in distance education. Athabasca: Athabasca University Press; 2010.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 .

Weerarathna RS, Rathnayake NM, Pathirana UPGY, Weerasinghe DSH, Biyanwila DSP, Bogahage SD. Effect of E-learning on management undergraduates’ academic success during COVID-19: a study at non-state Universities in Sri Lanka. Heliyon. 2023;9(9):e19293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19293 .

Bossman A, Agyei SK. Technology and instructor dimensions, e-learning satisfaction, and academic performance of distance students in Ghana. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):e09200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E09200 .

Mushtaha E, Abu Dabous S, Alsyouf I, Ahmed A, Raafat AN. The challenges and opportunities of online learning and teaching at engineering and theoretical colleges during the pandemic. Ain Shams Eng J. 2022;13(6):101770. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ASEJ.2022.101770 .

Wester ER, Walsh LL, Arango-Caro S, Callis-Duehl KL. Student engagement declines in STEM undergraduates during COVID-19–driven remote learning. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2021;22(1):22.1.50. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v22i1.2385 .

Lemay DJ, Bazelais P, Doleck T. Transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2021;4:100130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100130 .

Briggs MA, Thornton C, McIver VJ, Rumbold PLS, Peart DJ. Investigation into the transition to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, between new and continuing undergraduate students. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ. 2023;32:100430. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHLSTE.2023.100430 .

Nácher MJ, Badenes-Ribera L, Torrijos C, Ballesteros MA, Cebadera E. The effectiveness of the GoKoan e-learning platform in improving university students’ academic performance. Stud Educ Eval. 2021;70:101026. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.STUEDUC.2021.101026 .

Grønlien HK, Christoffersen TE, Ringstad Ø, Andreassen M, Lugo RG. A blended learning teaching strategy strengthens the nursing students’ performance and self-reported learning outcome achievement in an anatomy, physiology and biochemistry course—a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;52:103046. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEPR.2021.103046 .

De Paola M, Gioia F, Scoppa V. Online teaching, procrastination and student achievement. Econ Educ Rev. 2023;94:102378. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONEDUREV.2023.102378 .

Goodwin J, Kilty C, Kelly P, O’Donovan A, White S, O’Malley M. Undergraduate student nurses’ views of online learning. Teach Learn Nurs. 2022;17(4):398–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TELN.2022.02.005 .

Realyvásquez-Vargas A, Maldonado-Macías AA, Arredondo-Soto KC, Baez-Lopez Y, Carrillo-Gutiérrez T, Hernández-Escobedo G. The impact of environmental factors on academic performance of university students taking online classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):9194.

Hollister B, Nair P, Hill-Lindsay S, Chukoskie L. Engagement in online learning: student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Front Educ. 2022;7:851019. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.851019 .

Hsu HC, Wang CV, Levesque-Bristol C. Reexamining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Educ Inf Technol. 2019;24(3):2159–74.

Bradley VM. Learning Management System (LMS) use with online instruction. Int J Technol Educ. 2021;4(1):68–92.

Clark AE, Nong H, Zhu H, Zhu R. Compensating for academic loss: online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Econ Rev. 2021;68:101629.

Bacher-Hicks A, Goodman J, Mulhern C. Inequality in household adaptation to schooling shocks: Covid-induced online learning engagement in real time. J Public Econ. 2021;193:1043451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104345 .

Liu YM, Hou YC. Effect of multi-disciplinary teaching on learning satisfaction, self-confidence level and learning performance in the nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;55:103128.

Gelles LA, Lord SM, Hoople GD, Chen DA, Mejia JA. Compassionate flexibility and self-discipline: Student adaptation to emergency remote teaching in an integrated engineering energy course during COVID-19. Educ Sci (Basel). 2020;10(11):304.

Deng Y, et al. Family and academic stress and their impact on students’ depression level and academic performance. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:869337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869337 .

Gunderson M, Oreopolous P. Returns to education in developed countries. In: The economics of education; 2020. p. 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00003-3 .

Prasetyo PE, Kistanti NR. Human capital, institutional economics and entrepreneurship as a driver for quality & sustainable economic growth. Entrep Sustain Issues. 2020;7(4):2575. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.7.4(1) .

Cents-Boonstra M, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, Denessen E, Aelterman N, Haerens L. Fostering student engagement with motivating teaching: an observation study of teacher and student behaviours. Res Pap Educ. 2021;36(6):754–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1767184 .

Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, et al. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z .

Werang BR, Leba SMR. Factors affecting student engagement in online teaching and learning: a qualitative case study. Qualitative Report. 2022;27(2):555–77. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5165 .

Heilporn G, Lakhal S, Bélisle M. An examination of teachers’ strategies to foster student engagement in blended learning in higher education. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2021;18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00260-3 .

Gopal R, Singh V, Aggarwal A. Impact of online classes on the satisfaction and performance of students during the pandemic period of COVID 19. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2021;26:6923–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10523-1 .

Schnitzler K, Holzberger D, Seidel T. All better than being disengaged: student engagement patterns and their relations to academic self-concept and achievement. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36(3):627–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00500-6 .

Roksa J, Kinsley P. The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Res High Educ. 2019;60:415–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9517-z .

Antoni J. Disengaged and nearing departure: Students at risk for dropping out in the age of COVID-19. TUScholarShare Faculty/Researcher Works; 2020. https://doi.org/10.34944/dspace/396 .

Cavinato AG, Hunter RA, Ott LS, Robinson JK. Promoting student interaction, engagement, and success in an online environment. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021;413:1513–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-021-03178-x .

Kumar S, Todd G. Effectiveness of online learning interventions on student engagement and academic performance amongst first-year students in allied health disciplines: a systematic review of the literature. Focus Health Prof Educ Multi-Prof J. 2022;23(3):36–55. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.668657139008083 .

Download references

The authors did not receive funding from any agency/institution for this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sydani Institute for Research and Innovation, Sydani Group, Abuja, Nigeria

Catherine Nabiem Akpen, Stephen Asaolu & Hilary Okagbue

Sydani Group, Abuja, Nigeria

Sunday Atobatele & Sidney Sampson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CNA, SOA, SA, and SS initiated the topic, CNA, HO and SOA searched and screened the articles, CNA, SOA, and HO conducted the data synthesis for the manuscript, CNA wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, CNA and SOA wrote the second draft of the manuscript, and SOA, HO and SA provided supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stephen Asaolu .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests regarding this research work.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Akpen, C.N., Asaolu, S., Atobatele, S. et al. Impact of online learning on student's performance and engagement: a systematic review. Discov Educ 3 , 205 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00253-0

Download citation

Received : 18 July 2024

Accepted : 05 September 2024

Published : 01 November 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00253-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Online learning

- Student engagement

- Student performance

- Systematic review

- Literature review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Shifting online during COVID-19: A systematic review of teaching and learning strategies and their outcomes

Joyce hwee ling koh, ben kei daniel.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2022 Apr 4; Accepted 2022 Aug 12; Issue date 2022.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

This systematic literature review of 36 peer-reviewed empirical articles outlines eight strategies used by higher education lecturers and students to maintain educational continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic since January 2020. The findings show that students’ online access and positive coping strategies could not eradicate their infrastructure and home environment challenges. Lecturers’ learning access equity strategies made learning resources available asynchronously, but having access did not imply that students could effectively self-direct learning. Lecturers designed classroom replication, online practical skills training, online assessment integrity, and student engagement strategies to boost online learning quality, but students who used ineffective online participation strategies had poor engagement. These findings indicate that lecturers and students need to develop more dexterity for adapting and manoeuvring their online strategies across different online teaching and learning modalities. How these online competencies could be developed in higher education are discussed.

Keywords: Online learning, E-learning, Emergency response teaching, COVID-19, Online dexterity, Online pedagogy

Introduction

Higher education institutions have launched new programmes online for three decades, but their integration of online teaching and learning into on-campus programmes remained less cohesive (Kirkwood & Price, 2014 ). Since early 2020, educational institutions have been shifting online in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some consider this kind of emergency remote teaching a temporary online shift during a crisis, whereas online learning involves purposive design for online delivery (Hodges et al., 2020 ). Two years into the pandemic, fully online, blended or hybridised modalities are still being used in response to evolving COVID-19 health advisories (Jaschik, 2021 ). Even though standards for the pedagogical, social, administrative, and technical requirements of online learning have already been published before the pandemic (e.g. Bigatel et al., 2012 ; Goodyear et al., 2001 ), the online competencies of lecturers and students remain critical challenges for higher education institutions during the pandemic (Turnbull et al., 2021 ). Emerging systematic literature reviews about higher education online teaching and learning during the pandemic focus on the clinical aspects of health science programmes (see Dedeilia et al., 2020 ; Hao et al., 2022 ; Papa et al., 2022 ). Understanding the strategies used in other programmes and disciplines is critical for outlining higher education lecturers’ and students’ future online competency needs.

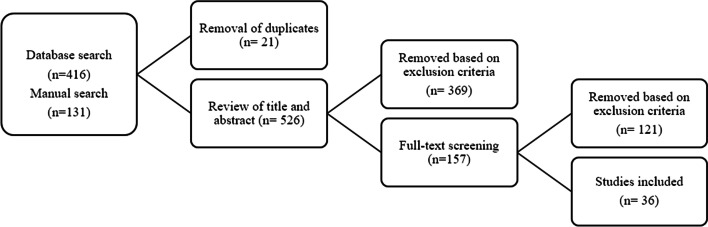

This study, therefore, presents a systematic literature review of the teaching and learning strategies that lecturers and students used to shift online in response to the pandemic and their consequent outcomes. The review was conducted through content analysis and thematic analysis of 36 peer-reviewed articles published from January 2020 to December 2021. It discusses how relevant online competencies for lecturers and students can be further developed in higher education.

Methodology

A Systematic and Tripartite Approach (STA) (Daniel & Harland, 2017 ) guided the review process. STA draws from systematic review approaches such as the Cochrane Review Methods, widely used in application-based disciplines such as the health sciences (Chandler & Hopewell, 2013 ). It develops systematic reviews through description (providing a summary of the review), synthesis (logically categorising research reviewed based on related ideas, connections and rationales), and critique (providing evidence to support, discard or offer new ideas about the literature).

Framing the review

The following research questions guided the review:

What strategies did higher education lecturers and students use when they shifted teaching and learning online in response to the pandemic?

What were the outcomes arising from these strategies?

Search strategy

Peer-reviewed articles were identified from databases indexing leading educational journals—Educational Database (ProQuest), Education Research Complete (EBSCOhost), ERIC (ProQuest), Scopus, Web of Science (Core Collection), and ProQuest Central. The following search terms were used to locate articles with empirical evidence of lecturers’ and/or students’ shifting online strategies:

(remote OR virtual OR emergency remote OR online OR digital OR eLearning) AND (teaching strateg* OR learning strateg* OR shifting online) AND (higher education OR tertiary OR university OR college) AND (covid*) AND (success OR challenge OR outcome OR effect OR case OR lesson or evidence OR reflection)

The following were the inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Review period—From January 2020 to December 2021, following the first reported case of COVID-19 (WHO, 2020 ).

Language—Only articles published in the English language were included.

Type of article—In order maintain rigour in the findings, only peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings were included, and non-refereed articles and conference proceedings were excluded. Peer-reviewed articles reporting empirical data from the lecturer and/or student perspectives were included. Editorials and literature reviews were examined to deepen conceptual understanding but excluded from the review.

The article’s focus—Articles with adequate descriptions and evaluation of lecturers’ and students’ online teaching and learning strategies undertaken because of health advisories during the COVID-19 pandemic were included. K-12 studies, higher education studies with data gathered prior to January 2020, studies describing general online learning experiences that did not arise from COVID-19, studies describing the functionalities of online learning technologies, studies about tips and tricks for using online tools during COVID-19, studies about the public health impact of COVID-19, or studies purely describing online learning attitudes or successes and challenges during COVID-19 without corresponding descriptions of teaching and learning strategies and their outcomes were excluded.

A list of 547 articles published between January 2020 and December 2021 were extracted using keyword and manual search with a final list of 36 articles selected for review (see Fig. 1 ). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the PRISMA process (Moher et al., 2009 ). The articles and a summary of coding are found in Appendix .

Article screening with the PRISMA process

Data analysis

Content analysis (Weber, 1990 ) and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ) were used to answer the research questions. Pertinent sections of each article outlining lecturers’ and/or students’ shifting online strategies were identified, read and re-read for data familiarisation. The first author used content analysis to generate eight teaching and learning strategies. These were verified through an inter-rater analysis where a random selection of eight articles was recoded by a second-rater (22.22% of total articles) and confirmed with adequate Cohen’s kappas (Teaching strategies: 0.88, Learning strategies: 0.78). Frequency counts were analysed to answer research question 1.

For the second research question, we first categorised the various shifting online outcomes described in each article and coded each outcome as “success”, “challenge”, or “mixed”. Successful outcomes include favourable descriptions of teaching, learning, or assessment experiences, minimal issues with technology/infrastructure, favourable test scores, or reasonable attendance/course completion rates, whereas challenging outcomes suggest otherwise. Mixed outcomes were not a success or challenge, for example, positive and negative experiences during learning, assessment or with learning infrastructure, or mixed learning outcomes such as positive test scores but lower ratings of professional confidence. Frequency distributions were used to compare the overall successes and challenges of shifting online (see Tables 1 and 2 of “ Findings ” section). Following this, the pertinent outcomes associated with each of the eight shifting online strategies were pinpointed through thematic analysis and critical relationships were visualised as theme maps. These were continually reviewed for internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity (Patton, 1990 ). To ensure trustworthiness and reliability (Creswell, 1998 ), there was frequent debriefing between the authors to refine themes and theme maps, followed by critical peer review with another lecturer specialising in higher education educational technology practices. Throughout this process, an audit trail was maintained to document the evolution of themes. These processes completed the description and synthesis aspects of the systematic literature review prior to critique and discussion (Daniel & Harland, 2017 ).

Descriptive characteristics

Success and challenges of shifting online

Descriptive characteristics of the articles are summarised in Table 1 .

Table 1 shows that articles about shifting online during the pandemic were published steadily between August 2020 and December 2021. About two-thirds of the articles were based on data from the United States of America, Asia, or Australasia, with close to 45% of the articles analysing shifting online strategies used in the disciplines of Natural Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences and around 60% focusing on degree programmes. While there was an exact representation of studies with sample sizes from below 50 to above 150, the majority were descriptive studies, with close to half based on quantitative data gathered through surveys. About half of the articles focused on teaching strategies, while around 40% also examined students' learning strategies. However, only about 20% of the articles had theoretical framing for their teaching strategies. Besides using self-developed theories, the authors also used established theories such as the Community of Inquiry Theory by Garrison et. al. ( 2010 ), the Interaction Framework for Distance Education by Moore ( 1989 ), self-regulated learning by Zimmerman ( 2002 ) and the 5E model of Bybee et. al. ( 2006 ). Different types of shifting online outcomes were reported in the articles. The majority documented the positive and negative experiences associated with synchronous or asynchronous online learning activities, online learning technology and infrastructure, or online assessment. A quarter of the articles reported data on student learning outcomes and attendance/completion rates, while a minority also described teaching workload effects. Table 2 shows other successes and challenges associated with shifting online. Of the articles that examined online learning experiences, over a quarter reported clear successes in terms of positive experiences while about half reported mixed experiences. Majority of the articles examining technology and infrastructure experiences or assessment experiences either reported challenging or mixed experiences. All the articles examining learning outcomes reported apparent successes but only half of those investigating attendance/completion rates found these to be acceptable. Only challenges were reported for teaching workload.

Teaching strategies and outcomes

Lecturers used five teaching strategies to shift online during the pandemic (see Table 3 ).

Teaching strategies

Online practical skills training

Lecturers had to create online practical skills training . With limited access to clinical, field-based, or laboratory settings, lecturers taught only the conceptual aspects of practical skills through online guest lectures, live skill demonstration sessions, video recordings of field trips, conceptual application exercises, or by substituting skills practice with new theoretical topics (Chan et al., 2020 ; de Luca et al., 2021 ; Dietrich et al., 2020 ; Dodson & Blinn, 2021 ; Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Gomez et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ). Only in three studies about forest operations, ecology, and nursing was it possible to practice hand skills in alternative locations such as public parks and students’ homes (Dodson & Blinn, 2021 ; Gerhart et al., 2021 ; Palmer et al., 2021 ).

Outcomes : Online practical skills training had different effects on learning experiences, test scores, and attendance/completion rates. Students can attain expected test scores through conceptual learning of practical skills (Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Gomez et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ). However, not all students had positive learning experiences as some appreciated deeper conceptual learning, but others felt disconnected from peers, anxious about losing hand skills proficiency, and could not maintain class attendance (de Luca et al., 2021 ; Dietrich et al., 2020 ; Gomez et al., 2020 ). Positive learning experiences, reasonable course attendance/completion rates, and higher confidence in content mastery were more achievable when students had opportunities to practice hand skills in alternative locations (Gerhart et al., 2021 ).

Online assessment integrity

Lecturers had to devise strategies to maintain online assessment integrity , primarily through different ways of preventing cheating (see Reedy et al., 2021 ). Pass/Fail grading, reducing examination weightage through a higher emphasis on daily work and class participation, and asking students to make academic integrity declarations were some changes to examination policies (e.g. Ali et al., 2020 ; Dicks et al., 2020 ). Randomising and scrambling questions, administering different versions of examination papers, using proctoring software, open-book examinations, and replacing multiple choice with written questions were other ways of preventing cheating during online examinations (Hall et al., 2021 ; Jaap et al., 2021 ; Reedy et al., 2021 ).

Outcomes : There was concern that shifting to online assessment had detrimental effects on learning outcomes, but several studies reported otherwise (Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Gomez et al., 2020 ; Hall et al., 2021 ; Jaap et al., 2021 ; Lapitan et al., 2021 ). Nevertheless, there were mixed assessment experiences. When lecturers changed multiple-choice to written critical thinking questions, it made students perceive that examinations have become harder (Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Khan et al., 2022 ). Some students were anxious about encountering technical problems during online examinations, while others felt less nervous taking examinations at home (Jaap et al., 2021 ). Students also became less confident about the integrity of assessment processes when lecturers failed to set clear rules for open-book examinations (Reedy et al., 2021 ). While Pass/Fail grading alleviated students’ test performance anxiety, some lecturers felt that this lowered academic standards (Dicks et al., 2020 ; Khan et al., 2022 ). More emphasis on daily work alleviated student anxiety as examination weightage was reduced, but students also perceived a corresponding increase in course workload as they had more assignments to complete (e.g. Dietrich et al., 2020 ; Swanson et al., 2021 ).

Classroom replication

Lecturers used classroom replication strategies to foster regularity, primarily through substituting classroom sessions with video conferencing under pre-pandemic timetables (Palmer et al., 2021 ; Simon et al., 2020 ; Zhu et al., 2021 ). Lecturers also annotated their presentation materials and decorated their teaching locations with content-related backdrops to emulate the ‘chalk and talk’ of physical classrooms (e.g. Chan et al., 2020 ; Dietrich et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ).

Outcomes : Regular video conferencing classes helped students to maintain course attendance/completion rates (e.g. Ahmed & Opoku, 2021 ; Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Gerhart et al., 2021 ). Student engagement improved when lecturers annotated on Powerpoint™ or digital whiteboards during video conferencing (Hew et al., 2020 ). However, screen fatigue commonly affected concentration, and lecturers had challenges assessing social cues effectively, especially when students turned off their cameras (Khan et al., 2022 ; Lapitan et al., 2021 ; Marshalsey & Sclater, 2020 ). Lecturers tried to shorten class duration with asynchronous activities, only to find students failing to complete their assigned tasks (Grimmer et al., 2020 ).

Learning access equity

Lecturers implemented learning access equity strategies so that those without stable network connections or conducive home environments could continue studying (Abou-Khalil et al., 2021 ; Ahmed & Opoku, 2021 ; Dodson & Blinn, 2021 ; Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Grimmer et al., 2020 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ; Khan et al., 2022 ; Marshalsey & Sclater, 2020 ; Pagoto et al., 2021 ; Swanson et al., 2021 ; Yeung & Yau, 2021 ). They equalised learning access by making lecture recordings available, using chat to communicate during live classes, and providing supplementary asynchronous activities (e.g. Gerhart et al., 2021 ; Grimmer et al., 2020 ). Some lecturers only delivered lessons asynchronously through pre-recorded lectures and online resources (e.g. de Luca et al., 2021 ; Dietrich et al., 2020 ). In developing countries, lecturers created access opportunities by sending learning materials through both learning management systems and WhatsApp™ (Kapasia et al., 2020 ).

Outcomes : Learning access strategies maintained some level of student equity through asynchronous learning but created challenging student learning experiences. There is evidence that students could achieve expected test scores through asynchronous learning (Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ) but maintaining learning consistency was a challenge, especially for freshmen (e.g. Grimmer et al., 2020 ; Khan et al., 2022 ). Some students found it hard to understand difficult concepts without in-person lectures but they also did not actively attend the live question-and-answer sessions organised by lecturers (Ali et al., 2020 ; Dietrich et al., 2020 ; Gomez et al., 2020 ). Poorly designed lecture recordings and unclear online learning instructions from lecturers compounded these problems (Gomez et al., 2020 ; Yeung & Yau, 2021 ).

Student engagement

Lecturers used two kinds of student engagement strategies, one of which was through active learning. Hew et. al. ( 2020 ) fostered active learning through 5E activities (Bybee et al., 2006 ) that encouraged students to Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, and Evaluate. Lapitan et. al. ( 2021 ) implemented active learning through their DLPCA process, where students Discover, Learn and Practice outside of class with content resources and Collaborate in class before Assessment. Chan et. al. ( 2020 ) used their Theory of Change to support active learning through shared meaning-making. Other studies emphasised active learning but did not reference theoretical frameworks (e.g. Martinelli & Zaina, 2021 ). Many described how lecturers used interactive tools such as Nearpod™, and Padlet™, online polling, and breakout room discussions to encourage active learning (e.g. Ali et al., 2020 ; Gomez et al., 2020 ).

Another student engagement strategy was through regular communication and support, where lecturers sent emails, announcements, and reminders to keep students in pace with assignments (e.g. Abou-Khalil et al., 2021 ). Support was also provided through virtual office hours, social media contact after class hours and uploading feedback over shared drives (e.g. Khan et al., 2022 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ).

Outcomes : Among the student engagement strategies, success in test scores tends to be associated with the use of active learning (Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Gomez et al., 2020 ; Hew et al., 2020 ; Lapitan et al., 2021 ; Lau et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, positive learning experiences were more often reported when lecturers emphasised care and empathy through their communication (e.g. Chan et al., 2020 ; Conklin & Dikkers, 2021 ). Students felt this more strongly when lecturers used humour, conversational and friendly tone, provided assurance, set clear expectations, exercised flexibility, engaged their feedback to improve online lessons, and responded swiftly to their questions (e.g. Chan et al., 2020 ; Swanson et al., 2021 ). These interactions fostered the social presence of Garrison et. al.’s ( 2010 ) Community of Inquiry Theory (Conklin & Dikkers, 2021 ). However, keeping up with multiple communication channels increased teaching workload, especially when support requests arrived through social media after work hours (Garcia-Alberti et al., 2021 ; Khan et al. 2022 ; Marshalsey & Sclater, 2020 ).

Learning strategies and outcomes

Students used three learning strategies during the pandemic (see Table 4 ).

Learning strategies

Online access

Students had to maintain online access , as institutional support for data and technology was rarely reported (Ahmed & Opoku, 2021 ; Laher et al., 2021 ). Students did so by switching to more reliable internet service providers, purchasing more data, borrowing computing equipment, or switching off webcams during class (Kapasia et al., 2020 ; Mahmud & German, 2021 ).

Outcomes : Unstable internet connections, noisy home environments, tight study spaces, and disruptions from family duties were challenges often reported in students’ learning environments (e.g. Castelli & Sarvary, 2021 ; Yeung & Yau, 2021 ). The power supply was unstable in developing countries and students also had limited financial resources to purchase data. To keep studying, these students relied on materials shared through WhatsApp™ groups or Google Drive™ and learnt using mobile phones even though their small screen sizes affected students’ learning quality (Kapasia et al., 2020 ).

Online participation

Students had to maintain online participation by redesigning study routines according to when lecturers posted lecture recordings, identifying personal productive hours, changing work locations at home to improve focus and concentration, and devising study strategies to use online resources effectively, such as through note-taking (e.g. Abou-Khalil et al., 2021 ; Mahmud & German, 2021 ; Marshalsey & Sclater, 2020 ). Students also adjusted their online communication style by taking the initiative to contact lecturers through email, discussion forums, or chat for support, and learning new etiquette for video conferencing (Abou-Khalil et al., 2021 ; Dietrich et al., 2020 ; Mahmud & German, 2021 ; Simon et al., 2020 ; Yeung & Yau, 2021 ). Students recognised the need for active online participation (Yeung & Yau, 2021 ) but most tended to switch off webcams and avoided speaking up during class (Ahmed & Opoku, 2021 ; Castelli & Sarvary, 2021 ; Dietrich et al., 2020 ; Khan et al., 2022 ; Lapitan et al., 2021 ; Marshalsey & Sclater, 2020 ; Munoz et al., 2021 ; Rajab & Soheib, 2021 ).

Outcomes : Mahmud and German ( 2021 ) found that students lack the confidence to plan their study strategies, seek help, and manage time. Students also lacked confidence and switched off webcams out of privacy concerns or because they felt self-conscious about their appearances and home environments (Marshalsey & Sclater, 2020 ; Rajab & Soheib, 2021 ). Too many turned off webcams and this became a group norm (Castelli & Sarvary, 2021 ). Classes eventually became dominated by more vocal students, making the quieter ones feel left out (Dietrich et al., 2020 ).

Positive coping

Students’ positive coping strategies included family support, rationalising their situation, focusing on their future, self-motivation, and making virtual social connections with classmates (Ando, 2021 ; Laher et al., 2021 ; Mahmud & German, 2021 ; Reedy et al., 2021 ; Simon et al., 2020 ).

Outcomes : Positive coping strategies helped students to improve learning experiences, maintain attendance/completion rates, and avoid academic integrity violations during online examinations (Ando, 2021 ; Reedy et al., 2021 ; Simon et al., 2020 ). However, these strategies cannot circumvent technology and infrastructure challenges (Mahmud & German, 2021 ), while the realities of economic, family, and health pressures during the pandemic threatened their educational continuity and caused some to manifest negative coping behaviours such as despondency and overeating (Laher et al., 2021 ).

Higher education online competencies

This systematic review outlined eight teaching and learning strategies for shifting online during the pandemic. Online teaching competency frameworks published before the pandemic advocate active learning, social interaction, and prompt feedback as critical indicators of online teaching quality (e.g. Bigatel et al., 2012 ; Crews et al., 2015 ). The findings suggest that lecturers’ student engagement strategies aligned with these standards, but they also needed to adjust practical skills training, assessment, learning access channels, and classroom teaching strategies. Students’ online participation and positive coping strategies reflected how online learners could effectively manage routines, schedules and their sense of isolation (Roper, 2007 ). Since most students had no choice over online learning during the pandemic (Dodson & Blinn, 2021 ), those lacking personal motivation or adequate infrastructure had to develop online participation and online access strategies to cope with the situation.

The eight teaching and learning strategies effectively maintained test scores and attendance/completion rates, but many challenges surfaced during teaching, learning, and assessment. Turnbull et. al. ( 2021 ) attribute lecturers’ and students’ pandemic challenges to online competency gaps, particularly in digital literacy or competencies for accessing information, analysing data, and communicating with technology (Blayone et al., 2018 ). However, the study findings show that digital literacy may not be enough for students to overcome infrastructure and home environment challenges in their learning environment. Lecturers can try helping students mitigate these challenges by providing asynchronous resource access through access equity strategies. Yet, students may not successfully learn asynchronously unless they can effectively self-direct learning. Lecturers may have pedagogical knowledge to create engaging active online learning experiences. How these strategies effectively counteract students’ inhibitions to turn on webcams and speak up during class remains challenging. Lectures may also have the skills to set up different online communication channels, but students may not actively engage if care and empathy are perceived to be lacking. Furthermore, lecturers’ online assessment strategies may not always balance academic integrity with test validity.

These findings show that online competencies are not just standardised technical or pedagogical skills (e.g. Goodyear et al., 2001 ) but “socially situated” (Alvarez et al., 2009 , p. 322) abilities for manoeuvring strategies according to situation and context (Hatano & Inagaki, 1986 ). It encompasses “dexterity” or finesse with skill performance (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). The pandemic demands one to be “flexible and adaptable” (Ally, 2019 , p. 312) amidst shifting national, institutional and learning contexts. Online dexterity is needed in several areas. Online learning during the pandemic is rarely unimodal. Establishing the appropriate synchronous-asynchronous blend is a critical pedagogical decision for lecturers. They need dexterity across learning modalities to create the “right” blend in different student, content, and technological contexts (Baran et al., 2013 ; Martin et al., 2019 ). Lecturers also need domain-related dexterity to preserve authentic learning experiences while converting subject content online (Fayer, 2014 ). Especially when teaching skill-based content under different social distancing requirements, competencies to maintain learning authenticity through simulations, alternative locations, or equipment may be critical (e.g. Schirmel, 2021 ). Dexterity with online assessment is also essential. Besides preventing cheating, lecturers need to ensure that online assessments retain test validity, improve learning processes and are effective for performance evaluation (AERA, 2014 ; Sadler & Reimann, 2018 ). Another area is the dexterity to engage in online communication that appropriately manifests care and empathy (Baran et al., 2013 ). Since online teaching increases lecturers’ workload (Watermeyer et al., 2021 ), dexterity to balance student care and self-care without compromising learning quality is also crucial.

Access to conducive learning environments critically affects students’ online learning success (Kapasia et al., 2020 ). While some infrastructure challenges cannot be prevented, students should have the dexterity to mitigate their effects. For example, when disconnected from class because of bandwidth fluctuations, students should be able to find alternative ways of catching up with the lecturer rather than remaining passive and frustrated (Ezra et al., 2021 ). Self-direction is critical during online learning because it is the ability to set learning goals, self-manage learning processes, self-monitor, self-motivate, and adjust learning strategies (Garrison, 1997 ). Students need the dexterity to manage self-direction processes across different courses, learning modalities, and learning schedules. Dexterity to create an active learning presence through using appropriate learning etiquette and optimising the affordances of text, audio, video, and shared documents during class is also essential. This can support students' cognitive, social, and emotional engagement across synchronous and asynchronous modalities, individually or in groups (Zilvinskis et al., 2017 ).

Future directions

Online learning is highly diverse and increasingly dynamic, making it challenging to cover all published work for review. In this study, we have analysed pandemic-related teaching and learning strategies and their outcomes but recognise that a third of the studies were from the United States and close to half from natural or health science programmes. The findings cannot fully elucidate the strategies implemented in unrepresented countries or disciplines. Recognising these limitations, we propose the following as future directions for higher education:

Validate post-pandemic relevance of online teaching and learning strategies