It is the membership that makes the Institute

For over 40 years, The Institute of Clinical Research (The ICR) has provided high quality training, networking and support to the clinical research community. For many Members the Institute has been part of their life throughout their working careers, many have been with the Institute since its first incarnation as the ACRPI.

Defining and refining standards for our profession

Providing a forum for discussion of key issues impacting clinical research

Promoting good relations with other healthcare related groups

Raising standards, developing professionals, sharing knowledge

We achieve results through passion and dedication

A structured approach to maintaining, improving and broadening professional knowledge and personal qualities that enable clinical researchers

Become a part of the Clinical Research community

Over the years, the ICR has held many different Forums and Special Interest Groups.

Clinical Research Training

A broad range of training from industry experts

Clinical Research Information

Providing insight into the clinical research world

The Institute of Clinical Research The Institute of Clinical Research

Quick contact.

Support – Research – Community

Send your query or request a callback

Business Hours : Monday – Thursday : 10:00 to 16:00 BST Friday – Sunday: Closed

07955 680 944

Subscribe to our mailing list

+44 79 55 680 944.

© 2012 - 2024All Rights Reserved • The Institute of Clinical Research • Powered by Easy2Access

Registered Company Address 11 Lyons Walk Shaftesbury Dorset SP7 8JF

+44 7955 680 944

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

The nih almanac, clinical center (cc).

- Important Events

- Legislative Chronology

The NIH Clinical Center is the nation's largest hospital devoted entirely to clinical research. Clinician-investigators translate scientific observations and laboratory discoveries into new approaches to diagnosing, treating, and preventing disease. The Clinical Center was recognized with the 2011 Lasker~Bloomberg Public Service Award for serving as a model research hospital—providing innovative therapy and high-quality patient care, treating rare and severe diseases, and producing outstanding clinician-scientists whose collective work has set a standard of excellence in biomedical research.

About 1,600 clinical research studies are in progress at the Clinical Center. Half are studies of the natural pathogenesis of disease, especially rare diseases, which often are not studied anywhere else. What researchers learn by studying rare diseases adds to the basic understanding of common diseases. Most other studies are clinical trials, the first tests of new drugs and therapies in people. The clinical trials at the Clinical Center are predominantly Phase I and Phase II—first-in-human to test safety and efficacy. Clinical and laboratory research is conducted shoulder-to-shoulder, and this tandem approach drives all aspects of the Clinical Center’s operations.

More than 500,000 research volunteers have participated in clinical research studies at the Clinical Center since the hospital opened in 1953. Each year, the center sees about 10,000 new research participants , who are split into two types: patient volunteers and healthy volunteers . Patient volunteers are people with specific diseases or conditions who help medical investigators learn more about their condition or test new medications, procedures, or treatments. A healthy volunteer is a person with no known significant health problems who plays a vital role in research to test a new drug, device, or intervention.

At the Clinical Center, clinical research participants are active partners in medical discovery, a partnership that has resulted in a long list of medical milestones , including the first cure of a solid tumor with chemotherapy, gene therapy, use of AZT to treat AIDS, and successful replacement of a mitral valve.

Important Events in Clinical Center History

November 1948 — Construction of the Clinical Center is started.

June 22, 1951 — President Harry S. Truman is the honored guest for the Clinical Center's cornerstone ceremony.

July 2, 1953 — The Clinical Center is dedicated by Department of Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Oveta Culp Hobby.

July 6, 1953 — The first patient is admitted to the Clinical Center.

1954 — The NIH Clinical Center's diagnostic X-ray department acquires the only Schnonander angiocardiographic unit in the United States. It takes films in two planes at the rate of six films per second, permitting a graphic demonstration of contrast substances as they pass through the heart, making diagnosis faster and more accurate.

1957 — The Clinical Pathology Department develops the first automated machine for counting red and white blood cells (until then counted manually).

1957 — The Blood Bank publishes its first research paper, delineating the post-transfusion hepatitis problem, firing the first salvo in a long but largely successful campaign.

1959 — A new, circular surgical wing is built.

September 1963 — A new surgical wing for cardiac and neurosurgery was dedicated by Surgeon General Luther L. Terry.

1963 — The Blood Bank moves to a new area and blood collections begin on the NIH campus.

1964 — Drs. Harvey Alter (Clinical Center) and Baruch Blumberg (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) co-discover the Australian antigen, which Blumberg later shows to be the surface coating of the hepatitis B virus, leading to the isolation of this medically important virus. Blumberg later wins the Nobel Prize. Alter, who later receives the Lasker Award, does pioneering work in the causes and prevention of blood-transmitted infections, which helps lead to the discovery of the virus that causes hepatitis C and the development of screening methods that will reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis.

1964 — Dr. John L. Doppman and associates in diagnostic radiology report the first successful imaging of the arteries that supply the spinal cord. The technique of spinal angiography makes surgical intervention possible where spinal arterial malformations, lesions, or tumors cause paralysis.

1966 — A Nuclear Medicine Department is established in the NIH Clinical Center.

1966 — Wanda S. Chappell, chief nurse in the Blood Bank, comes up with a simple but ingenious method for separating blood platelets (the smallest blood cells) from blood plasma, so that the platelets can be used for transfusion to leukemia patients and the rest of the blood can be used by others, including patients undergoing open heart surgery.

1968 — Diagnostic radiologist Dr. John L. Doppman develops a method for locating the parathyroid, a group of glands (each about the size of a BB pellet) that regulates calcium metabolism.

1970 — The Blood Bank switches to an all-volunteer donor system, and adds a test for hepatitis B surface antigen. Those two measures alone reduce the hepatitis rate from 30 percent before 1970 to about 11 percent after. Later, when it adds more sensitive tests for hepatitis B, the virus virtually disappears as a problem in the Blood Bank .

1972 — Blood Bank scientists develop a test for the antigen associated with hepatitis. The test will eventually be used nationally.

1976 — An electronic medical information system — one of the nation's first — is introduced at the NIH Clinical Center.

April 1977 — Construction of the ambulatory care research facility is started.

November 1977 — The Critical Care Medicine Department is established.

1977 — The Blood Bank establishes therapeutic apheresis/exchange programs that for decades will improve the lifespan and welfare of patients with such illnesses as sickle cell disease, hyperlipidemia, and autoimmune disorders. It also establishes the first automated platelet-pheresis center, collecting platelets for transfusion from volunteer donors using automated instrumentation.

1980 — The research hospital is renamed the Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center, in honor of the former chairman of the Senate Committee on Appropriations, who has actively supported biomedical research at NIH since 1937. (P.L. 96-518.)

June 16, 1981 — The first patient with the new disease, later to be named AIDS/HIV, is seen at the NIH Clinical Center.

1981 — Clinical research dietitians develop standards of care for the clinical nutrition service and devise diets with controlled intake of certain nutrients to support clinical research.

1982 — A new surgical facility and a surgical intensive care unit opens.

March 22, 1984 — The first magnetic resonance imaging unit becomes operational for patient imaging.

1984 — The Clinical Center Blood Bank is renamed the Department of Transfusion Medicine because its activities extend well beyond traditional blood banking. DTM achieves the first transmission of HIV (HTLV III) to a primate through transfusion and describes the HIV seronegative window.

April 13, 1985 — Two cyclotrons are delivered to the underground facility operated by the Nuclear Medicine Department.

1986 — The Clinical Center signs an agreement to become one of the first donor centers participating in the National Marrow Donor Program.

September 14, 1990 — A 4-year-old patient with adenosine deaminate deficiency is the first to receive gene therapy treatment.

April 8, 1991 — The Department of Transfusion Medicine opens its state-of-the-art facility.

July 1993 — The hematology/bone marrow unit opens to improve transplant procedures and develop gene therapy techniques.

May 1994 — A multi-institute unit designed and staffed for children opens.

1995 — The course “ Introduction to the Principles and Practice of Clinical Research ” is first offered. It provides education in the basics of safe, ethical, and efficient clinical research.

February 1996 — Details on clinical research studies conducted at the Clinical Center are made available online at http://clinicalstudies.info.nih.gov/ , increasing opportunities for physicians and patient volunteers to participate in NIH clinical investigations.

November 1996 — A Board of Governors is appointed by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, marking a new governing system for the Clinical Center.

July 1997 — The Department of Transfusion Medicine launches a 3,000-square feet model core [cGMP] cell processing facility, created to meet increasing investigative needs for cell products used in new cellular therapies such as immunotherapy, gene therapy, stem cell transplantation, and pancreatic islet cell transplantation.

November 4, 1997 — Vice President Al Gore and Senator Mark O. Hatfield attend groundbreaking ceremonies for the Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center, designed to include a new hospital and research laboratories.

1999 — The Clinical Pathology Department is renamed the Department of Laboratory Medicine .

1999 — The Bench-to-Bedside Awards program is established to speed translation of promising laboratory discoveries into new medical treatments by encouraging collaborations among basic scientists and clinical investigators.

2000 — The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Clinical Center (in collaboration with Walter Reed Army Medical Center, the Naval Medical Research Center, and the Diabetes Research Institute of the University of Miami) launch a new kidney, pancreas, and islet transplant program. The idea is to test novel therapies that may eliminate the need for the immunosuppressive drugs patients take to keep their bodies from rejecting new transplanted organs.

2000 — The Clinical Center launches a new Pain and Palliative Care Consult Service .

2000 — The Imaging Sciences Program takes first steps toward filmless radiology, unveiling the pilot phase of its new Picture Archiving and Communication System and Radiology Information System.

2001 — A second bone marrow transplant unit opens to support the National Cancer Institute protocols.

2002 — The Department of Transfusion Medicine establishes a model program for collecting blood from subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis . This program supplies 10 percent of the hospital's red cell needs.

October 29, 2002 — A groundbreaking ceremony is held for the Edmond J. Safra Family Lodge . Located steps away from the Clinical Center, the lodge provides a comfortable home away from home for the families and caretakers of Clinical Center patients.

2003 — The Office of Clinical Research Training and Medical Education is established to help train the next generation of clinical researchers.

2004 — As recommended by the NIH Director's Blue Ribbon Panel on the Future of Intramural Clinical Research, the former Clinical Center Board of Governors assumes a new and larger identity, becoming the NIH Advisory Board for Clinical Research. The board oversees all intramural clinical research, while continuing its oversight of Clinical Center resources, planning, and operations.

2004 — The NIH Clinical Center formalizes an emergency preparedness partnership with Suburban Hospital and the National Naval Medical Center.

August 21, 2004 — The NIH Clinical Center's updated electronic Clinical Research Information System goes live.

September 22, 2004 — The dedication ceremony is held for the Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center.

2005 — Radiologist Dr. Ronald M. Summers finds that computer-aided software, in conjunction with a procedure commonly called virtual colonoscopy, can deliver results comparable to conventional colonoscopy for detecting the most worrisome types of polyps.

2005 — Bioethics chief Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel co-authors a study suggesting that minority involvement in clinical research is more a matter of access than attitude.

2005 — The Rehabilitation Medicine Department opens its clinical movement analysis lab, a joint venture with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child health and Human Development.

April 2, 2005 — Patients are moved into the Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center and the building becomes fully operational.

May 26, 2005 — An opening ceremony is held for the Edmond J. Safra Family Lodge . The lodge opens its doors to guests on June 1.

2006 — The Bench-to-Bedside Awards program extends to include intramural and extramural collaborations.

2006 — Nursing and Patient Care Services initiates a collaboration with the Indian Health Service to increase clinical nursing research capabilities.

2007 — The first of 1,000 volunteers are enrolled in a study led by the National Human Genome Research institute to test the use of human genome sequencing in a clinical research study.

January 25, 2007 — A ribbon-cutting ceremony is held for a new NIH metabolic clinical research unit that provides researchers from multiple institutes the opportunity to study obesity and related conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers.

2008 — The Undiagnosed Diseases Program is established, led by the National Human Genome Research Institute, the NIH Office of Rare Diseases, and the NIH Clinical Center to help and learn from patients who have eluded diagnosis.

2008 — Clinical Center nurses undertake a multi-year project to define the clinical research domain of practice and lead the way in establishing it as a recognized nursing specialty practice.

2008 — An adaptation of the Clinical Center course “ Introduction to the Principles and Practice of Clinical Research ” is presented in Beijing.

2008 — The Clinical Center begins a partnership with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and the Department of Defense to conduct clinical research studies in the fields of neuroscience and regenerative medicine. The research involves military and civilian populations.

2009 — Two new trans-NIH imaging resources are initiated, the Center for Interventional Oncology and the Center for Infectious Diseases Imaging .

July 2009 — The Biomedical Translational Research Information System , launches its NIH-wide intramural research data repository allowing investigators to view identified data from their active protocols. By December, intramural researchers are able to access de-identified data from clinical and research systems across the NIH intramural programs. BTRIS is designed to facilitate hypothesis generation, data gathering, and analysis.

2009 — The Department of Transfusion Medicine begins use of a prototype cell expansion system to automate bone marrow stromal cell expansion.

2009 — Computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography /CT equipment purchased by the Clinical Center is now required to routinely record radiation dose exposure in a patient's hospital-based electronic medical record.

January 2010 — The Pharmacy Department opens a state-of-the-art pharmaceutical development facility where staff formulate and analyze vaccines and medications not available from manufacturers. These products account for one-third of the drugs (including placebos and varying strengths) that the Clinical Center uses in its research protocols.

April 2010 — The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases seven-bed Special Clinical Studies Unit opens, with advanced isolation and extended-stay capabilities.

June 2011 — The Clinical Center graduates 12 interns from the pilot NIH- Project SEARCH internship program, providing employment opportunities and experience for young adults with developmental disabilities.

September 2011 — The Clinical Center is named the 2011 recipient of the Lasker~Bloomberg Public Service Award from the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation. The award honors the Clinical Center for serving as a model institution that has transformed scientific advances into innovative therapies and provided high-quality care to patients.

October 2011 — The Clinical Center acquires one of the first fully integrated whole-body simultaneous positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging devices.

February 2012 — The Clinical Center established a Memorandum of Understanding allowing NIH intramural clinical studies of children under the age of two in the Clinical and Translational Science Award clinical unit at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, DC.

March 2012 — A new Joint Taskforce between the Clinical Center and the Food and Drug Administration was created to consider exceptions to existing Investigational New Drug policies and procedures for extraordinary clinical circumstances.

August 2012 — Researchers from the NIH Clinical Center and National Human Genome Research Institute published a novel use of genome sequencing to help quell Klebsiella pneumonia bacteria outbreak at the Clinical Center in Science and Translational Medicine.

August 2012 — The NIH Clinical Center announces a new grant program, Opportunities for Collaborative Research at the hospital, which will support partnerships to expand engagement with extramural investigators interested in collaborating with intramural researchers, using the Clinical Center’s unique resources.

September 2012 — The first class of the new NIH Medical Research Scholars Program started the year-long research enrichment program, engaging in a mentored basic, clinical, or translational research project that matches their professional interests and career goals.

October 2013 — The Clinical Center’s Drs. Julie Segre, Evan Snitkin, Tara Palmore, and David Henderson earn the title "Federal Employees of the Year" for their breakthrough in tracking and controlling of a cluster of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections at the Clinical Center with the use of DNA sequencing.

March 2014 — The The NIH Clinical Center is opened to non-government researchers through three-year renewable research grants of up to $500,000 per year. The new program will allow scientists to collaborate with NIH investigators in a highly specialized hospital setting as they work toward translating promising laboratory discoveries into improved disease diagnosis, prevention, and treatment.

October 2014 — The NIH Clinical Center admits its first patient with the Ebola virus , which causes an acute, serious illness which is often fatal if untreated. The patient was treated in the Special Clinical Studies Unit which is specifically designed to provide high-level isolation capabilities and is staffed by infectious diseases and critical care specialists. She was discharged Oct. 24, declared free of the Ebola virus, after five negative PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests.

September 2015 — The NIH Clinical Center was announced as the first federal medical facility to be recognized by Health Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) Analytics. The Clinical Center was awarded the research hospital Stage 7 certification, the highest level attainable, for its electronic medical record adoption model, eliminating the use of paper charts and maintaining a superior electronic medical record system for inpatient care.

March 2016 — A photon-counting computed tomography (CT) scanner is used in patients for the first time at the NIH Clinical Center. The prototype technology is expected to replicate the image quality of conventional CT scanning, but may also provide health care specialists with an enhanced look inside the body through multi-energy imaging.

January 2017 — Dr. James K. Gilman serves as the first chief executive officer of the NIH Clinical Center.

August 2017 — " First in Human " a three-part documentary series about the NIH Clinical Center’s staff and patients airs. The program, produced by The Discovery Channel, highlights the innovation and hard work that takes place in the hospital, depicts how challenging illness are diagnosed and treated and provides an inside look at the successes and setbacks that are a part of experimental medicine.

August 2017 — Researchers from the NIH Clinical Center's Rehabilitation Medicine Department created the first robotic exoskeleton specifically designed to treat crouch (or flexed-knee) gait in children. Crouch gait, the excessive bending of the knees while walking, is a common and debilitating condition in children with cerebral palsy. The exoskeleton provides powered knee extension assistance to support patients at key points during the walking cycle.

July 2018 — The NIH Clinical Center opens a Hospice Unit as a part of its Medical Oncology section. The unit is comprised of two rooms that have been converted into a home-like environment where families can stay with adult patients who are nearing end of life. Each suite has a bedroom and a communal space, including a kitchen and family sitting area.

October 2020 — NIH Clinical Center researcher Dr. Harvey J. Alter wins the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contributions to the discovery of the hepatitis C virus. Alter, a Senior Scholar in the hospital’s Department of Transfusion Medicine, shares the award with Michael Houghton, PhD, from the University of Alberta in Canada and Charles M. Rice, PhD, from Rockefeller University in New York City. Dr. Alter’s career at NIH has spanned more than 50 years where he focused his research on the occurrence of hepatitis in patients who had received blood transfusions.

October 2021 — The NIH Clinical Center unveils Treasure Tour , a free game application aimed at children, teens and their families to better help them understand the layout of the hospital, the programs and services offered onsite and the procedures and tests patients might undergo. Treasure Tour provides a look at six different patient care areas of the Clinical Center. Players can explore the hospital's pediatric clinic, one of the day hospitals, an inpatient unit, the phlebotomy lab, radiology and imaging sciences and the Department of Perioperative Medicine. All are presented in a kid-friendly way and are easily recognizable to anyone who has visited, or will soon visit, the hospital. Treasure Tour can be played on web-based platforms and downloaded to iOS devices in the App Store or to Android devices in the Google Play Store.

2022 — The NIH Clinical Center expands pediatric services ; looking at early interventions that may cure diseases and prevent negative outcomes that can occur in some rare diseases. The hospital's Pediatric Consult Service became the Department of Pediatrics, and one of the first initiatives was to establish the Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) service with the goal of creating 24/7 pediatric, age appropriate care by in-house hospitalists.

CC Legislative Chronology

July 1, 1944 — Public Law 78-410, the Public Health Service Act, authorized establishment of the Clinical Center.

July 8, 1947 — Under P.L. 80-165, research construction provisions of the Appropriations Act for FY 1948 provided funds "For the acquisition of a site, and the preparation of plans, specifications, and drawings, for additional research buildings and a 600-bed clinical research hospital and necessary accessory buildings related thereto to be used in general medical research."

December 12, 1980 — Senate Joint Resolution 213 designates the Clinical Center as the "Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health."

September 12, 1996 — House Resolution 3755, Section 218, named the new clinical research center at the National Institutes of Health as the Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center.

Biographical Sketch of Clinical Center Chief Executive Officer Dr. James K. Gilman

Selected as the first chief executive officer (CEO) for the NIH Clinical Center in December 2016, Dr. Gilman oversees day-to-day operations and management of the research hospital on NIH's Bethesda campus – one of the largest such facilities in the world. Dr. Gilman guides the overall performance of the Clinical Center, focusing particularly on setting a high bar for patient safety and quality of care, including the development of new hospital operations policies.

Dr. Gilman earned a degree in biological engineering at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in 1974 and an MD at the Indiana University School of Medicine in 1978. He is board certified in both Internal Medicine and Cardiovascular Diseases and is a fellow of the American College of Cardiology and the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Gilman served 35 years in the U.S. Army, culminating as major general of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Fort Detrick, Maryland. He led several Army hospitals during his career — Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas; Walter Reed Health Care System, Washington, D.C.; and Bassett Army Community Hospital, Fort Wainwright, Alaska. He also served as director of Health Policy and Services responsible for all aspects of professional activities and healthcare policy in the Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Army Medical Command.

Following his retirement from the U.S. Army in 2013 as a major general, Dr. Gilman served as executive director of Johns Hopkins Military & Veterans Institute in Baltimore.

Clinical Center Directors

Clinical center chief executive officers, major programs.

As America's research hospital, the NIH Clinical Center leads the global effort in training today's investigators and discovering tomorrow's cures.

The Clinical Center's mission is to provide a versatile clinical research environment enabling the NIH mission to improve human health by:

- Investigating the pathogenesis of disease

- Conducting first-in-human clinical trials with an emphasis on rare diseases and diseases of high public health impact

- Developing state-of-the-art diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic interventions

- Training the current and next generation of clinical researchers

- Ensuring that clinical research is ethical, efficient, and of high scientific quality

Major components: Administrative Management; Bioethics; Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics; Clinical Research Informatics; Clinical Research Training and Medical Education; Communications and Media Relations; Credentials Services; Critical Care Medicine; Edmond J. Safra Family Lodge; Financial Resource Management; Hospital Epidemiology; Housekeeping and Fabric Care; Hospitality Services; Internal Medicine Consults; Laboratory Medicine; Laboratory for Informatics Development; Management Analysis and Reporting; Materials Management; Medical Records; Nursing; Nutrition; Pain and Palliative Care; Patient Recruitment; Perioperative Medicine; Pharmacy; Purchasing and Contracts; Rehabilitation Medicine; Transfusion Medicine; Pediatric Consults; Protocol Services; Radiology and Imaging Sciences; Social Work; Space and Facility Management; Spiritual Care Ministry; Veterinary Care; Workforce and Management Development.

This page last reviewed on March 5, 2024

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

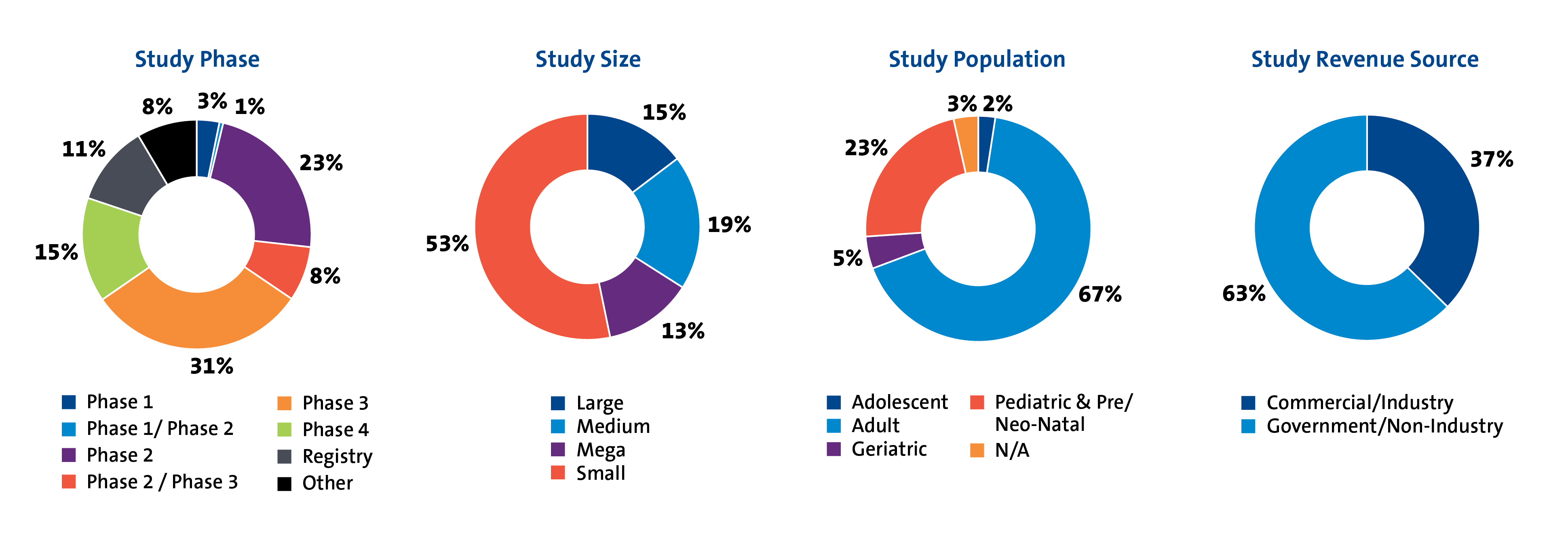

DCRI at a Glance

Our thought leadership influences the care of patients across the lifespan and extends to every phase of research—from early phase to post-market surveillance.

Our Studies

Clinical research must be designed in a way that gets to the answer clearly, accurately, and efficiently. Today, that means rethinking conventional approaches and introducing pragmatic methods to help speed study implementation.

LEARN ABOUT OUR OPERATIONAL CAPABILITIES

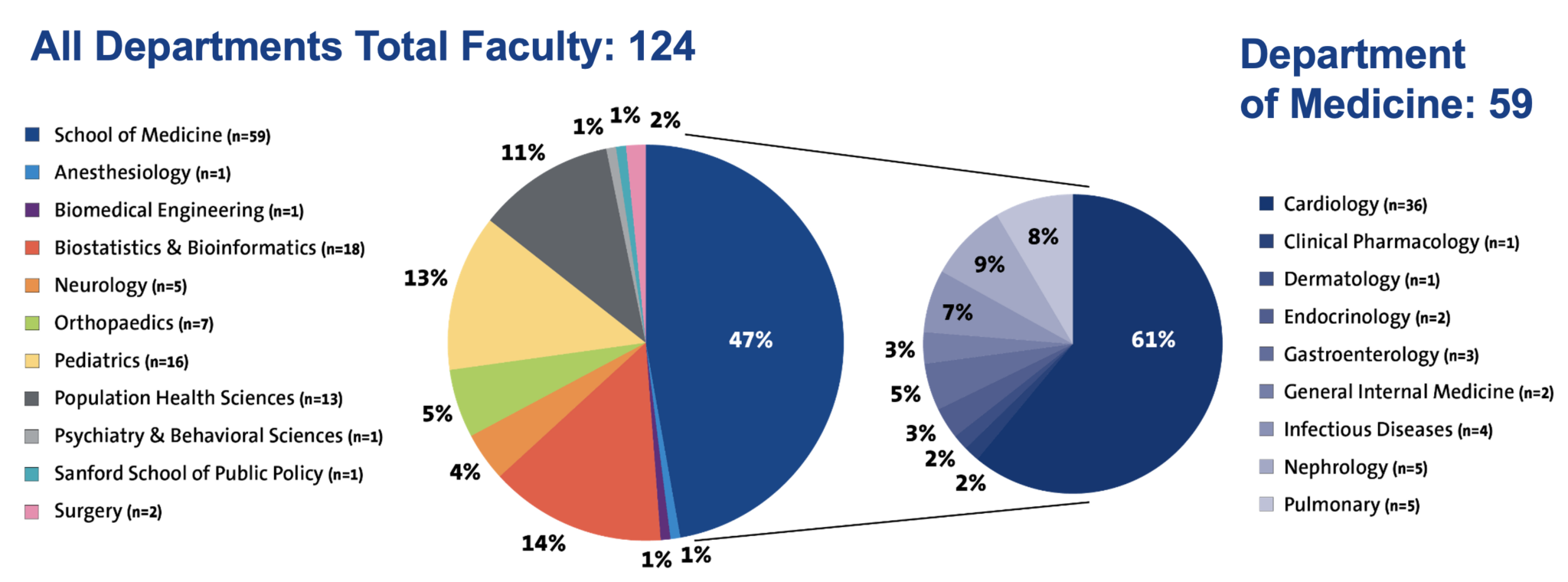

Our Faculty

Our faculty leaders are some of the world's foremost authorities on the science, study, and application of clinical research, making them uniquely positioned to understand the operational, financial, and regulatory implications of numerous project designs.

VIEW OUR FACULTY

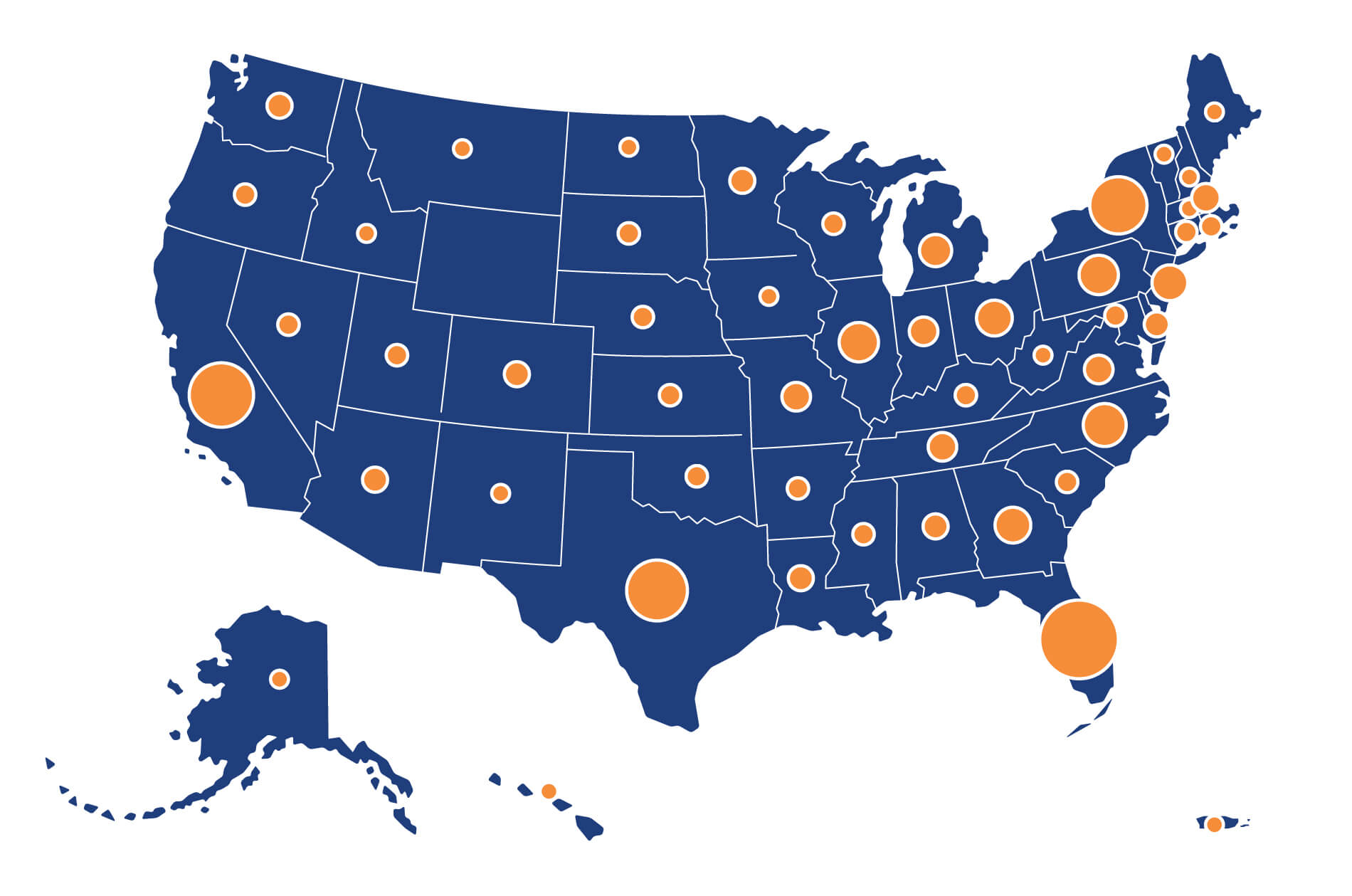

Our Site Network

The depth and breadth of DCRI’s collaborations reach around the globe to more than 40 countries. In the U.S. alone, the DCRI network touches every state plus Puerto Rico, with nearly 1,600 sites.

JOIN OUR SITE NETWORK

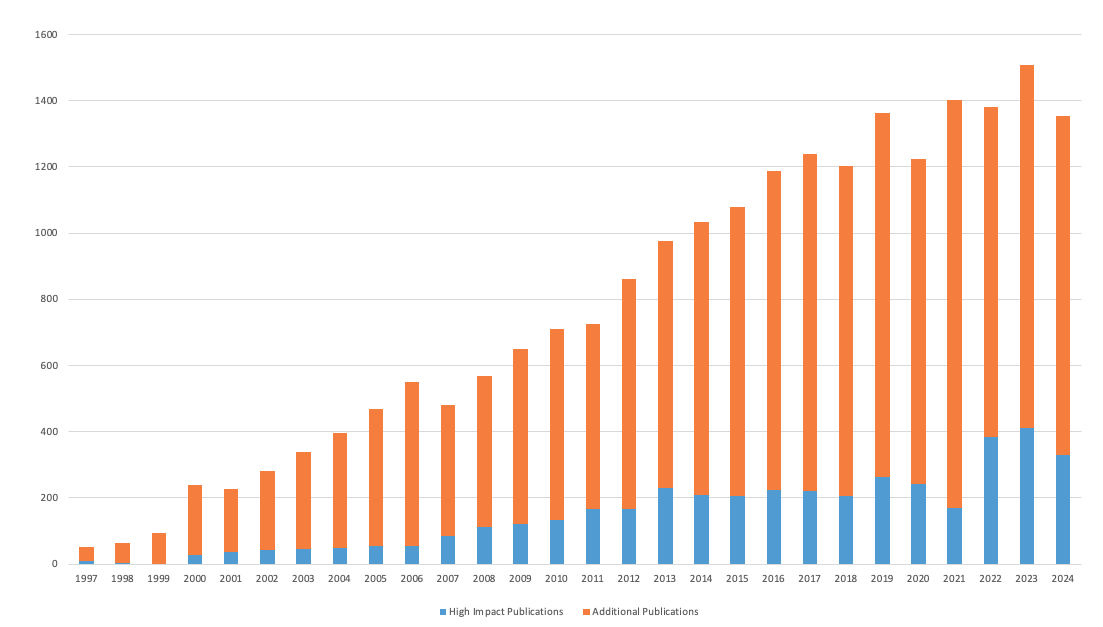

Our Publications

DCRI’s mission is to develop and share knowledge that improves health around the world through innovative clinical research. One of the primary ways in which we do this is through scientific publications. The DCRI has produced over 18,400 publications since 1996.

LEARN ABOUT DCRI PUBLICATIONS

Celebrating 25 Years of Improving Health Around the World

Formally founded in 1996, the DCRI followed in the footsteps of Duke pioneers who envisioned novel ways to learn about health and health care. An enduring spirit of innovation has enabled the institute to affect change in most every aspect of clinical research and realize our mission to improve health around the world.

LEARN MORE ABOUT DCRI'S LEGACY & VISION

DCRI's Annual Report Archive

Defining how research should be done and leading the way in doing it has been the bedrock of the DCRI for decades. Look back at how the DCRI has continually led the way forward by conducting research that is rapid, embedded, efficient, impactful, disruptive, and inclusive.

DCRI Annual Report 2019-2020 View PDF

DCRI Annual Report 2018-2019 View PDF

DCRI Annual Report 2017-2018 View PDF

DCRI Annual Report 2016-2017 View PDF

DCRI Annual Report 2015–2016 View PDF

DCRI Annual Report 2014–2015 View PDF

Duke Clinical Research Institute

The largest academic research organization in the world, the DCRI is known for its pioneering research in cardiology but performs clinical research across the spectrum of diseases, ranging from:

- Phase I to phase IV clinical trials

- Outcomes and quality research

- Registries of more than 100,000 patients

- Economic and quality-of-life studies in populations spanning more than 20 therapeutic areas

The DCRI grew out of the Duke Databank for Cardiovascular Diseases, which is one of the world's largest repositories of follow-up on patients who have documented coronary heart disease (more than 200,000 patients have been enrolled to date). The DCRI has evolved into an organization with major efforts in clinical trials, outcomes research, and health policy, and the DCRI expanded beyond the cardiovascular therapeutic area beginning in 1996.

The DCRI faculty includes clinician researchers, biostatisticians, health economists, and health services researchers. Currently, the DCRI comprises approximately 1,300 employees, including more than 200 faculty from all disciplines. Most DCRI researchers are also active practicing physicians, studying the application of research to patient care.

Research Accomplishments

- Conducted studies at more than 3,500 sites in 64 countries

- More than 1,050,000 patients enrolled in DCRI studies

- More than 8,000 publications in peer-reviewed journals

- More than 730 phase I-IV trials and outcomes research projects completed

- More than 5,000 investigators worldwide

Training Program

The DCRI offers a living laboratory for investigators of the future by combining faculty interests in specific research questions with the multifaceted environment needed to do outcome-based studies.

Trainees at the DCRI have the opportunity to experience firsthand the features of conducting domestic and international clinical trials and outcomes studies, including activities such as:

- Protocol development

- Study operations

- Continuing medical education curricula development

- Clinical events adjudication

- Operational functions such as project and data management, site management, and use of information technology specific to multi-center clinical research studies

Each cardiovascular trainee at the DCRI develops a relationship with a primary mentor who bears the responsibility of guiding the trainee’s career development. Within cardiovascular medicine, trainees are recommended to focus on either cardiovascular outcomes or clinical trials. However, trainees who focus on outcomes generally also work with at least one clinical trial, and clinical trial trainees generally conduct at least one database project. The mentor is expected to assist the fellow in developing a broad range of experiences with different types of faculty, not just to have the fellow work in his or her own research projects.

DCRI fellows attend a weekly DCRI Clinical Research Conference in which fellows, faculty, and visiting researchers present work in progress. The fellows also invite external leaders in cardiovascular medicine to conduct two-day visiting professor sessions including intensive small seminars with the fellows.

A critical component of the training program is the intense interaction between the clinician researchers and statisticians. The philosophy of the training program is that the most successful investigators in cardiovascular medicine will be able to combine superior knowledge of clinical cardiology with quantitative principles in an interactive, teamwork-oriented environment.

Cardiovascular fellows also have the opportunity to participate in coursework for the Clinical Research Training Program to obtain a Masters in Health Sciences in Clinical Research during their research fellowship at DCRI. This program offers in-depth training regarding biostatistics, clinical research design and methodology, cost-effectiveness research, and health economics.

The clinical research training offered to cardiovascular fellows at DCRI is unparalleled and represents a distinct advantage for trainees interested in a career in academic medicine and clinical investigation.

Lesley Curtis, PhD Interim Director

Contact Information

Office : DCRI, North Pavilion, 2400 Pratt Street, Durham, NC 27705 Campus mail : DUMC Box 3850, Durham, NC 27710 Phone : 919-668-8749 Fax : 919-668-7103

For more information: dcri.duke.edu

Duke Clinical Research Institute's 25 Years of Vision

From the moment that Adrian Hernandez, MD, MHS , professor of medicine in cardiology, stepped to the helm of the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI) in May 2020, he faced the prospect of steering the organization through uncharted and fast-changing waters.

The world was in the early throes of the COVID-19 pandemic. The DCRI, the world’s largest academic clinical research organization, houses eight primary therapeutic areas, from musculoskeletal to neuroscience, under one roof. Now it was all hands on deck to face COVID. Experts in infectious disease, critical care, pediatrics, and cardiology alike pivoted to focus on pandemic-related research in addition to their primary research programs. Faculty and staff worked day and night to organize and launch new research programs aimed at answering urgent questions, such as understanding how frontline health care workers were affected by the pandemic and investigating whether approved drugs could be repurposed to treat COVID-19 symptoms at home. The DCRI soon became Duke University’s largest recipient of federal research dollars for COVID-19.

Things were changing not only within the DCRI, but across the entire clinical research ecosystem. Telehealth or virtual visits became commonplace, and it soon became clear that more research could be conducted remotely outside the clinic by leveraging digital health technologies and meeting patients in their communities. Faced with the need to rapidly develop COVID-19 vaccines, scientific processes that would normally take years were accelerated and completed successfully in a fraction of that time.

In response to the changing research world, Hernandez, who is also a vice dean for the Duke University School of Medicine, began to identify top priorities for the DCRI, among them a robust digital strategy and decentralized trials, which essentially take clinical trials to the subjects rather than gathering subjects together at a central site.

But as Hernandez charted the path for DCRI’s future and responded to so much change, he was also struck by what had held fast: the institute’s mission to develop, share, and implement knowledge that improves health around the world through innovative clinical research.

“DCRI’s employees are profoundly mission-oriented,” said Hernandez. “Everyone quickly leaned in to developing creative and trustworthy methods for addressing the most pressing questions of the pandemic.”

An Enduring Vision

Upon becoming executive director, Hernandez gently finessed the mission statement, changing “improving patient care around the world” to “improving health around the world” to reflect DCRI’s expertise in preventive care and health for all.

Overall, however, the thrust of the DCRI’s mission remains unchanged from what it was 25 years ago when the institute was founded by Robert Califf, MD (currently nominated for a second stint as commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration).

During this 25 th anniversary year, the DCRI has reflected on its first quarter-century — and on where the next quarter-century will take it. When current and former faculty and staff — including Hernandez and the other four individuals who have had a turn as executive director — talk about the institute, the theme that arises again and again is the DCRI’s enduring vision, which underpins its mission and activities.

“The Duke Clinical Research Institute, which was formally created 25 years ago, began with a vision: to usher in a different approach to learn about health and illness, and to apply these learnings to improve health care,” said Califf, who led the institute from its inception in 1996 until 2006.

Over the past 25 years, that vision has coalesced into five broad categories of endeavor:

Generating World-Class Evidence to Improve Health

Central to DCRI’s vision and mission is the process of evidence generation through clinical trials and observational studies. Cardiologist Robert Harrington, MD, who was the DCRI’s executive director between 2006 and 2012 and is now Arthur L. Bloomfield professor of medicine and chairman of the department of medicine at Stanford University, said collaboration was key.

Harrington said the DCRI always fostered a strong collaborative spirit both internally and externally. Projects succeeded because a unique bond formed among clinicians, statisticians, and operational experts who were able to work together seamlessly to deliver on research efforts. The DCRI was also successful in collaborating with academic partners and pharma companies outside its walls to complete successful studies and help advance development of new treatments.

The culture of mutual support and collaboration is deeply embedded in the DCRI, and Harrington expects it to continue to yield benefits even as technology and science evolve rapidly.

“There are a lot of questions in clinical medicine that we don’t know the answer to,” Harrington said. “And I’m confident that the next version of DCRI will focus on how we collect data and turn it into evidence and informed clinical practice going forward.”

Sharing and Implementing Knowledge Widely

As an academic institution, the DCRI regards peer-reviewed publication as an essential part of the research process because it enables researchers to share scientific findings with their peers across academia and industry.

Since DCRI’s inception in 1996, the institute has disseminated over 17,500 publications , and findings from the DCRI have been cited in over 760,000 scientific articles. Several researchers with ties to the DCRI are named year after year to a global “highly cited researchers” list , including cardiologist Eric Peterson, MD, MPH, who directed the institute from 2012 to 2018 and is now vice provost and senior associate dean for clinical research as well as vice president for health system research at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

DCRI’s commitment to sharing knowledge extends far beyond just academic publications. In recent years, the institute has become a leader in developing research summaries for lay audiences and implementing other strategies to share study results with people who participated in the studies.

The DCRI is also heavily focused on implementation science: determining the most effective ways to implement evidence-based therapies and treatment strategies into clinical practice. This focus is narrowing the gap between research projects and treatment protocols — a much-needed change in an environment in which it takes an average of 17 years for clinical trials results to be adopted into patient care.

“Researchers do research for many reasons, and many are driven by knowing the answer,” Peterson said. “But at the DCRI, it’s not just about that; it’s about helping patients. While we certainly do research for the academic and intellectual reasons, the main reason is to impact the world and learn about how we treat patients, and ultimately, how we can care for them better. To get to that spot, we need to disseminate the findings of our work.”

Creating Novel Methods that Accelerate Clinical Research

The DCRI could not generate evidence successfully without continuously developing novel methods to answer increasingly difficult questions and make research more efficient. From the explosion of big data to the rapid emergence and spread of a never-before-seen disease, recent events have underscored the need for great minds to work on new ways to solve problems.

The DCRI has employed novel approaches in many of its research projects, such as successfully conducting the demonstration project showing how to leverage the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet), or leading the way in newer, more flexible trial designs. Duke population health scientist Lesley Curtis, PhD , who led the institute as its interim executive director from 2018 to 2020, said that DCRI’s ability to create novel methods has helped the institute address urgent needs.

“DCRI creates new ways of doing things not just for the sake of creating new methods and new ways of doing things, but to solve specific problems,” she said. “And those problems are often barriers that prevent us from — or maybe impede us from — generating the kind of evidence that patients and clinicians need. It’s really imperative for us to keep our creative thinking caps on.”

Improving Health Equity through Our Research

As Hernandez looks to the future of the DCRI, he sees improving health equity as one of its most important goals. While the DCRI has long endeavored to improve health for all, Hernandez and other institute leadership know that greater steps must be taken to reach this goal.

Study teams, for example, must work to enroll more diverse study populations so that results from clinical trials can be accurately applied to all populations. There are many root causes for the current lack of diversity in the clinical trial environment, one of which is a lack of diversity in clinical trials leadership.

Hernandez has committed to addressing these and other related issues through instating a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) office within the DCRI. Longtime Duke and DCRI employee Linda Davidson-Ray, MA, was selected to lead this office. She is tasked with strengthening DEI efforts within the DCRI, collaborating with the Duke School of Medicine’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion , and developing a platform for health equity research that can be shared and built upon with external partners.

“Especially the last five years, we’ve seen these health inequities worsen in different areas of the country,” Hernandez said. “We have this national footprint where we can close the gap. We have the resolve to bring the best minds together, not only at DCRI or Duke, but with other partners as well across academia, industry, and government agencies. We’re directly trying to address this by bringing those stakeholders together to design the solutions, test them out, and then show what works and also what doesn’t work.”

Developing the Next Generation of Clinical Researchers

Perhaps the most critical part of DCRI’s vision, which will serve to advance both the institute and the clinical research field for the next 25 years, is its commitment to developing the next generation of clinical researchers.

Harrington began his research career as a fellow at the Duke Databank for Cardiovascular Disease, which laid the groundwork for the founding of the DCRI. Since then, under the leadership of Harrington and others, the DCRI Fellowship Program has been formalized and expanded, equipping over 300 trainees with the skills needed to lead the clinical trials of tomorrow. It includes trainees with a diverse range of expertise, from musculoskeletal research to nephrology to cardiology, and attracts trainees from across the globe, from Canada to Australia: thus far the program has trained 64 fellows from 22 non-U.S. countries.

But even before there was a formal fellowship program, training and mentoring were important values of the institute, ingrained into its mission from its earliest days.

“From the beginning, the forte of the DCRI was putting trainees into the mix of getting trials and outcomes studies done — working with the study coordinators and the data experts and the statisticians to learn how it's done,” Califf said.

And the consensus among directors past and present? That early mission still rings true today, and is delivered through DCRI’s vision.

“T he mission is as relevant today — even with some tweaks to the wording — as it was when we first put it into play 25 years ago,” Harrington said. “My advice to future DCRI directors: Stay focused on the mission.”

Kaitl in Jansen is a former senior communications specialist at the Duke Clinical Research Institute.

COVID-19 Research Studies

More information, about clinical center, clinical trials and you, participate in a study, referring a patient, about clinical research.

Research participants are partners in discovery at the NIH Clinical Center, the largest research hospital in America. Clinical research is medical research involving people The Clinical Center provides hope through pioneering clinical research to improve human health. We rapidly translate scientific observations and laboratory discoveries into new ways to diagnose, treat and prevent disease. More than 500,000 people from around the world have participated in clinical research since the hospital opened in 1953. We do not charge patients for participation and treatment in clinical studies at NIH. In certain emergency circumstances, you may qualify for help with travel and other expenses Read more , to see if clinical studies are for you.

Medical Information Disclaimer

Emailed inquires/requests.

Email sent to the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center may be forwarded to appropriate NIH or outside experts for response. We do not collect your name and e-mail address for any purpose other than to respond to your query. Nevertheless, email is not necessarily secure against interception. This statement applies to NIH Clinical Center Studies website. For additional inquiries regarding studies at the National Institutes of Health, please call the Office of Patient Recruitment at 1-800-411-1222

Find NIH Clinical Center Trials

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center Search the Studies site is a registry of publicly supported clinical studies conducted mostly in Bethesda, MD.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

For over 40 years, The Institute of Clinical Research (The ICR) has provided high quality training, networking and support to the clinical research community. For many Members the Institute has been part of their life throughout their working careers, many have been with the Institute since its first incarnation as the ACRPI.

The Duke Clinical Research Institute, part of the Duke University School of Medicine, is the world's largest academic clinical research organization. We conduct innovative research to deliver on our mission to share knowledge that improves health around the world. DCRI projects are led by renowned experts and physician scientists whose ...

Clinical Research Institute Mission Statement. The mission of the CRI is to promote and facilitate the conduct of clinical research for faculty and trainees while upholding the highest standards of excellence by assuring human subject investigation be performed ethically, responsibly, and professionally to contribute to the health sciences' body of knowledge.

Our insights and know-how are drawn both from the arena of clinical trials and from the real world of patient care and community health. Duke's commitment to cross-cutting research also offers unique opportunities for the DCRI to support innovative partnerships and projects— from geospatial mapping to biomedical engineering, to health economics.

The NIH Clinical Center, America's research hospital, provides a versatile clinical research environment enabling the NIH mission to improve human health by investigating the pathogenesis of disease; conducting first-in-human clinical trials with an emphasis on rare diseases and diseases of high public health impact; developing state-of-the-art diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic ...

Our thought leadership influences the care of patients across the lifespan and extends to every phase of research—from early phase to post-market surveillance. Our Studies Clinical research must be designed in a way that gets to the answer clearly, accurately, and efficiently. Today, that means rethinking conventional approaches and introducing pragmatic methods to help speed study ...

Duke Clinical Research Institute. The Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI) is devoted to conducting innovative, multi-center clinical research with a mission to develop and share knowledge that improves the care of patients. Overview.

Twenty-five years ago, Robert Califf, MD, founded the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI) with a mission to usher in a new approach to generating knowledge about health and illness, and to use that knowledge to improve health care. In marking the institute's 25th anniversary, the five people who have directed the DCRI —from Califf to current executive director Adrian Hernandez, MD, MHS ...

M.F. Vladimirsky Moscow Regional Clinical Research Institute (clinical studies of endoscopic methods of hemostasis) N.V. Sklifosovsky Research Institute of Emergency Medicine (development of methods of emergency gastroenterological care) A.N. Rychikh Scientific Research Center for Coloproctology (colorectal surgery, endoscopy)

Clinical research is medical research involving people The Clinical Center provides hope through pioneering clinical research to improve human health. We rapidly translate scientific observations and laboratory discoveries into new ways to diagnose, treat and prevent disease. More than 500,000 people from around the world have participated in ...