25 Thesis Statement Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

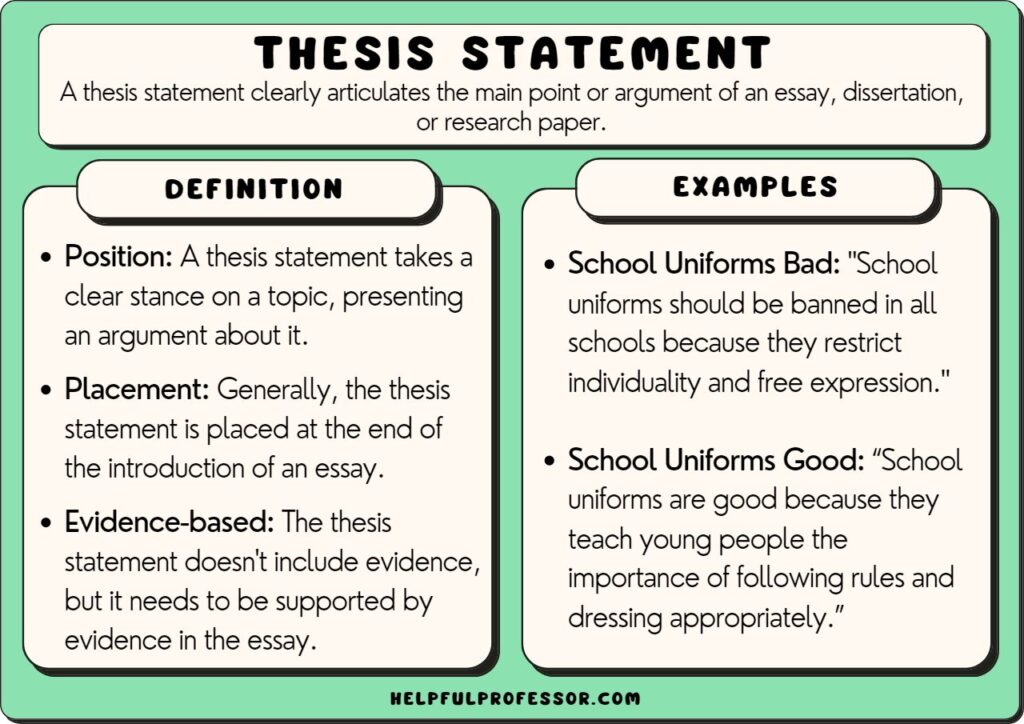

A thesis statement is needed in an essay or dissertation . There are multiple types of thesis statements – but generally we can divide them into expository and argumentative. An expository statement is a statement of fact (common in expository essays and process essays) while an argumentative statement is a statement of opinion (common in argumentative essays and dissertations). Below are examples of each.

Strong Thesis Statement Examples

1. School Uniforms

“Mandatory school uniforms should be implemented in educational institutions as they promote a sense of equality, reduce distractions, and foster a focused and professional learning environment.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay or Debate

Read More: School Uniforms Pros and Cons

2. Nature vs Nurture

“This essay will explore how both genetic inheritance and environmental factors equally contribute to shaping human behavior and personality.”

Best For: Compare and Contrast Essay

Read More: Nature vs Nurture Debate

3. American Dream

“The American Dream, a symbol of opportunity and success, is increasingly elusive in today’s socio-economic landscape, revealing deeper inequalities in society.”

Best For: Persuasive Essay

Read More: What is the American Dream?

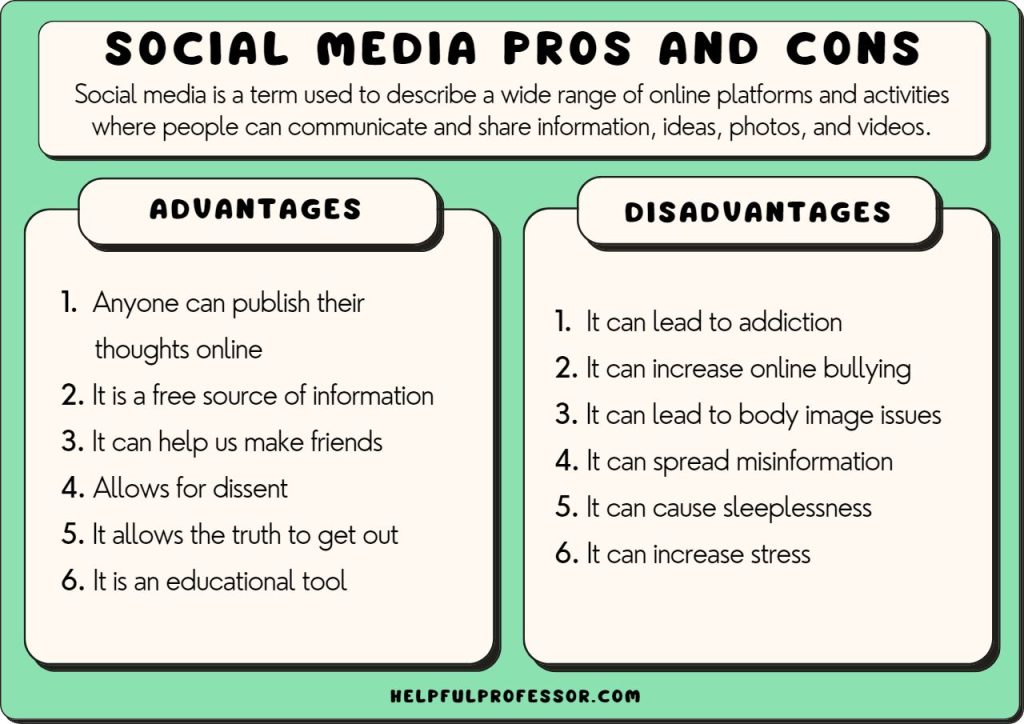

4. Social Media

“Social media has revolutionized communication and societal interactions, but it also presents significant challenges related to privacy, mental health, and misinformation.”

Best For: Expository Essay

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Social Media

5. Globalization

“Globalization has created a world more interconnected than ever before, yet it also amplifies economic disparities and cultural homogenization.”

Read More: Globalization Pros and Cons

6. Urbanization

“Urbanization drives economic growth and social development, but it also poses unique challenges in sustainability and quality of life.”

Read More: Learn about Urbanization

7. Immigration

“Immigration enriches receiving countries culturally and economically, outweighing any perceived social or economic burdens.”

Read More: Immigration Pros and Cons

8. Cultural Identity

“In a globalized world, maintaining distinct cultural identities is crucial for preserving cultural diversity and fostering global understanding, despite the challenges of assimilation and homogenization.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay

Read More: Learn about Cultural Identity

9. Technology

“Medical technologies in care institutions in Toronto has increased subjcetive outcomes for patients with chronic pain.”

Best For: Research Paper

10. Capitalism vs Socialism

“The debate between capitalism and socialism centers on balancing economic freedom and inequality, each presenting distinct approaches to resource distribution and social welfare.”

11. Cultural Heritage

“The preservation of cultural heritage is essential, not only for cultural identity but also for educating future generations, outweighing the arguments for modernization and commercialization.”

12. Pseudoscience

“Pseudoscience, characterized by a lack of empirical support, continues to influence public perception and decision-making, often at the expense of scientific credibility.”

Read More: Examples of Pseudoscience

13. Free Will

“The concept of free will is largely an illusion, with human behavior and decisions predominantly determined by biological and environmental factors.”

Read More: Do we have Free Will?

14. Gender Roles

“Traditional gender roles are outdated and harmful, restricting individual freedoms and perpetuating gender inequalities in modern society.”

Read More: What are Traditional Gender Roles?

15. Work-Life Ballance

“The trend to online and distance work in the 2020s led to improved subjective feelings of work-life balance but simultaneously increased self-reported loneliness.”

Read More: Work-Life Balance Examples

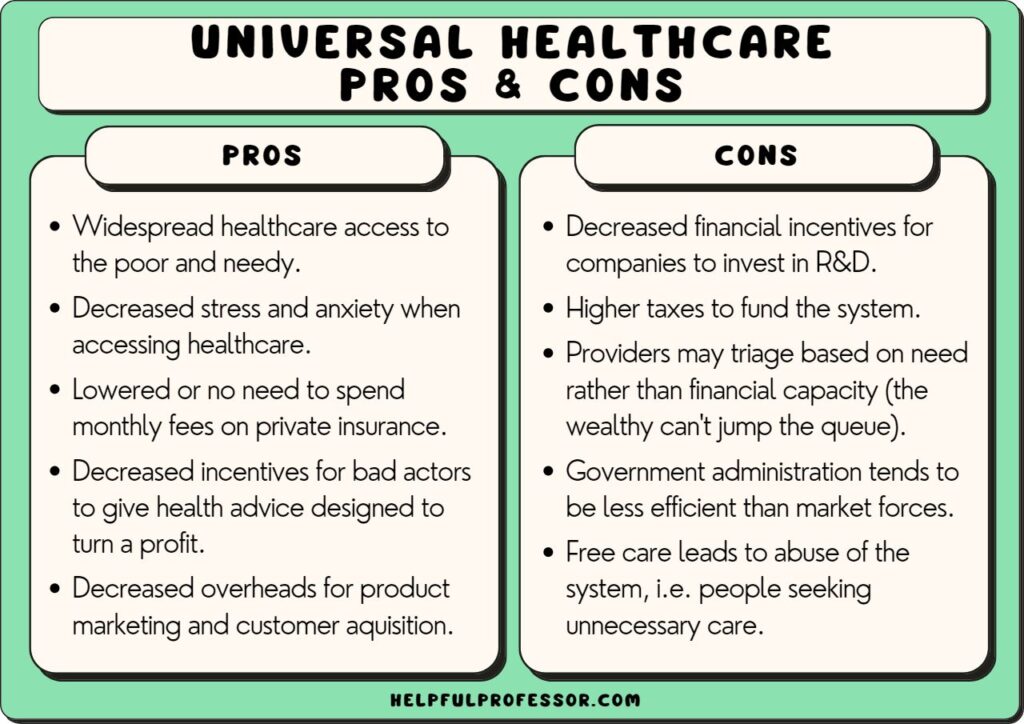

16. Universal Healthcare

“Universal healthcare is a fundamental human right and the most effective system for ensuring health equity and societal well-being, outweighing concerns about government involvement and costs.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Universal Healthcare

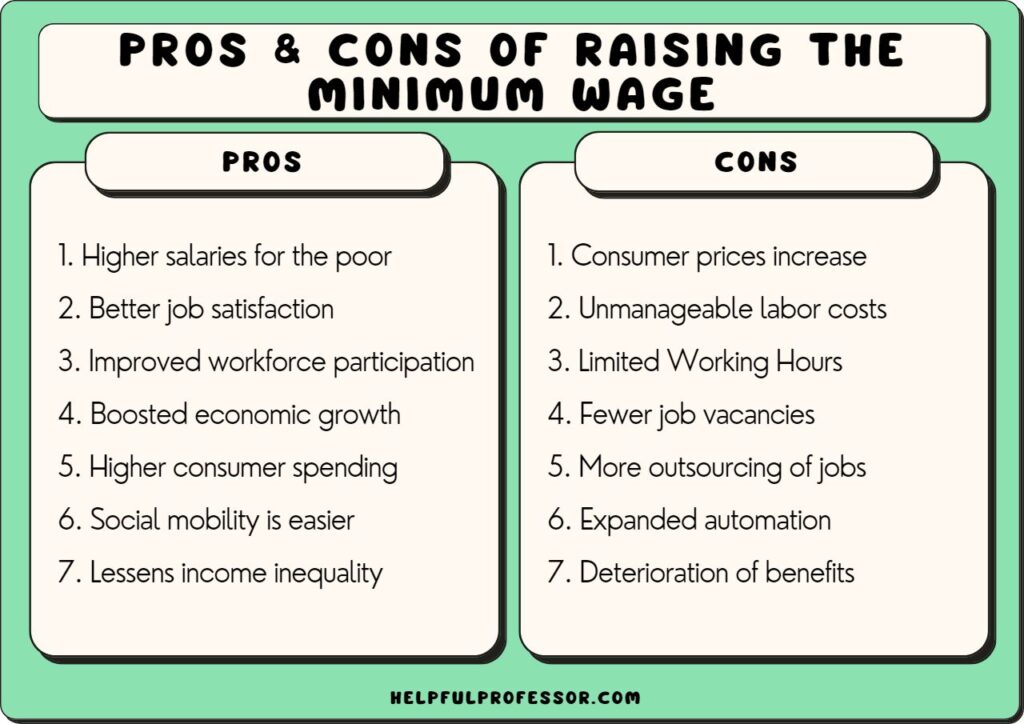

17. Minimum Wage

“The implementation of a fair minimum wage is vital for reducing economic inequality, yet it is often contentious due to its potential impact on businesses and employment rates.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Raising the Minimum Wage

18. Homework

“The homework provided throughout this semester has enabled me to achieve greater self-reflection, identify gaps in my knowledge, and reinforce those gaps through spaced repetition.”

Best For: Reflective Essay

Read More: Reasons Homework Should be Banned

19. Charter Schools

“Charter schools offer alternatives to traditional public education, promising innovation and choice but also raising questions about accountability and educational equity.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Charter Schools

20. Effects of the Internet

“The Internet has drastically reshaped human communication, access to information, and societal dynamics, generally with a net positive effect on society.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of the Internet

21. Affirmative Action

“Affirmative action is essential for rectifying historical injustices and achieving true meritocracy in education and employment, contrary to claims of reverse discrimination.”

Best For: Essay

Read More: Affirmative Action Pros and Cons

22. Soft Skills

“Soft skills, such as communication and empathy, are increasingly recognized as essential for success in the modern workforce, and therefore should be a strong focus at school and university level.”

Read More: Soft Skills Examples

23. Moral Panic

“Moral panic, often fueled by media and cultural anxieties, can lead to exaggerated societal responses that sometimes overlook rational analysis and evidence.”

Read More: Moral Panic Examples

24. Freedom of the Press

“Freedom of the press is critical for democracy and informed citizenship, yet it faces challenges from censorship, media bias, and the proliferation of misinformation.”

Read More: Freedom of the Press Examples

25. Mass Media

“Mass media shapes public opinion and cultural norms, but its concentration of ownership and commercial interests raise concerns about bias and the quality of information.”

Best For: Critical Analysis

Read More: Mass Media Examples

Checklist: How to use your Thesis Statement

✅ Position: If your statement is for an argumentative or persuasive essay, or a dissertation, ensure it takes a clear stance on the topic. ✅ Specificity: It addresses a specific aspect of the topic, providing focus for the essay. ✅ Conciseness: Typically, a thesis statement is one to two sentences long. It should be concise, clear, and easily identifiable. ✅ Direction: The thesis statement guides the direction of the essay, providing a roadmap for the argument, narrative, or explanation. ✅ Evidence-based: While the thesis statement itself doesn’t include evidence, it sets up an argument that can be supported with evidence in the body of the essay. ✅ Placement: Generally, the thesis statement is placed at the end of the introduction of an essay.

Try These AI Prompts – Thesis Statement Generator!

One way to brainstorm thesis statements is to get AI to brainstorm some for you! Try this AI prompt:

💡 AI PROMPT FOR EXPOSITORY THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTUCTIONS]. I want you to create an expository thesis statement that doesn’t argue a position, but demonstrates depth of knowledge about the topic.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR ARGUMENTATIVE THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTRUCTIONS]. I want you to create an argumentative thesis statement that clearly takes a position on this issue.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR COMPARE AND CONTRAST THESIS STATEMENT I am writing a compare and contrast essay that compares [Concept 1] and [Concept2]. Give me 5 potential single-sentence thesis statements that remain objective.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Free Social Skills Worksheets

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Much of the debate about identity in recent decades has been about personal identity, and specifically about personal identity over time, but identity generally, and the identity of things of other kinds, have also attracted attention. Various interrelated problems have been at the centre of discussion, but it is fair to say that recent work has focussed particularly on the following areas: the notion of a criterion of identity; the correct analysis of identity over time, and, in particular, the disagreement between advocates of perdurance and advocates of endurance as analyses of identity over time; the notion of identity across possible worlds and the question of its relevance to the correct analysis of de re modal discourse; the notion of contingent identity; the question of whether the identity relation is, or is similar to, the composition relation; and the notion of vague identity. A radical position, advocated by Peter Geach, is that these debates, as usually conducted, are void for lack of a subject matter: the notion of absolute identity they presuppose has no application; there is only relative identity. Another increasingly popular view is the one advocated by David Lewis: although the debates make sense they cannot genuinely be debates about identity, since there are no philosophical problems about identity. Identity is an utterly unproblematic notion. What there are, are genuine problems which can be stated using the language of identity. But since these can be restated without the language of identity they are not problems about identity. (For example, it is a puzzle, an aspect of the so-called “problem of personal identity”, whether the same person can have different bodies at different times. But this is just the puzzle whether a person can have different bodies at different times. So since it can be stated without the language of personal “identity”, it is not a problem about personal identity , but about personhood.) This article provides an overview of the topics indicated above, some assessment of the debates and suggestions for further reading.

1. Introduction

2. the logic of identity, 3. relative identity, 4. criteria of identity, 5. identity over time, 6. identity across possible worlds, 7. contingent identity, 8. composition as identity, 9. vague identity, 10. are there philosophical problems about identity, other internet resources, related entries.

To say that things are identical is to say that they are the same. “Identity” and “sameness” mean the same; their meanings are identical. However, they have more than one meaning. A distinction is customarily drawn between qualitative and numerical identity or sameness. Things with qualitative identity share properties, so things can be more or less qualitatively identical. Poodles and Great Danes are qualitatively identical because they share the property of being a dog, and such properties as go along with that, but two poodles will (very likely) have greater qualitative identity. Numerical identity requires absolute, or total, qualitative identity, and can only hold between a thing and itself. Its name implies the controversial view that it is the only identity relation in accordance with which we can properly count (or number) things: x and y are to be properly counted as one just in case they are numerically identical (Geach 1973).

Numerical identity is our topic. As noted, it is at the centre of several philosophical debates, but to many seems in itself wholly unproblematic, for it is just that relation everything has to itself and nothing else – and what could be less problematic than that? Moreover, if the notion is problematic it is difficult to see how the problems could be resolved, since it is difficult to see how a thinker could have the conceptual resources with which to explain the concept of identity whilst lacking that concept itself. The basicness of the notion of identity in our conceptual scheme, and, in particular, the link between identity and quantification has been particularly noted by Quine (1964).

Numerical identity can be characterised, as just done, as the relation everything has to itself and to nothing else. But this is circular, since “nothing else” just means “no numerically non-identical thing”. It can be defined, equally circularly (because quantifying over all equivalence relations including itself), as the smallest equivalence relation (an equivalence relation being one which is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, for example, having the same shape). Other circular definitions are available. Usually it is defined as the equivalence relation (or: the reflexive relation) satisfying Leibniz’s Law, the principle of the indiscernibility of identicals, that if x is identical with y then everything true of x is true of y . Intuitively this is right, but only picks out identity uniquely if “what is true of x ” is understood to include “being identical with x ”; otherwise it is too weak. Circularity is thus not avoided. Nevertheless, Leibniz’s Law appears to be crucial to our understanding of identity, and, more particularly, to our understanding of distinctness: we exhibit our commitment to it whenever we infer from “ Fa ” and “ Not-Fb ” that a is not identical with b . Strictly, what is being employed in such inferences is the contrapositive of Leibniz’s Law (if something true of a is false of b , a is not identical with b ), which some (in the context of the discussion of vague identity) have questioned, but it appears as indispensable to our grip on the concept of identity as Leibniz’s Law itself.

The converse of Leibniz’s Law, the principle of the identity of indiscernibles, that if everything true of x is true of y , x is identical with y , is correspondingly trivial if “what is true of x ” is understood to include “being identical with x ” (as required if Leibniz’s Law is to characterise identity uniquely among equivalence relations). But often it is read with “what is true of x ” restricted, e.g., to qualitative, non-relational, properties of x . It then becomes philosophically controversial. Thus it is debated whether a symmetrical universe is possible, e.g., a universe containing two qualitatively indistinguishable spheres and nothing else (Black 1952).

Leibniz’s Law has itself been subject to controversy in the sense that the correct explanation of apparent counter-examples has been debated. Leibniz’s Law must be clearly distinguished from the substitutivity principle, that if “ a ” and “ b ” are codesignators (if “ a = b ” is a true sentence of English) they are everywhere substitutable salva veritate . This principle is trivially false. “Hesperus” contains eight letters, “Phosphorus” contains ten, but Hesperus (the Evening Star) is Phosphorus (the Morning Star). Again, despite the identity, it is informative to be told that Hesperus is Phosphorus, but not to be told that Hesperus is Hesperus (“On Sense and Reference” in Frege 1969). Giorgione was so-called because of his size, Barbarelli was not, but Giorgione was Barbarelli (Quine, “Reference and Modality”, in 1963) . It is a necessary truth that 9 is greater than 7, it is not a necessary truth that the number of planets is greater than 7, although 9 is the number of planets. The explanation of the failure of the substitutivity principle can differ from case to case. In the first example, it is plausible to say that “‘Hesperus’ contains eight letters” is not about Hesperus, but about the name, and the same is true, mutatis mutandis , of “‘Phosphorus’ contains ten letters”. Thus the names do not have the same referents in the identity statement and the predications. In the Giorgione/Barbarelli example this seems less plausible. Here the correct explanation is plausibly that “is so-called because of his size” expresses different properties depending on the name it is attached to, and so expresses the property of being called “Barbarelli” because of his size when attached to “Barbarelli” and being called “Giorgione” because of his size when attached to “Giorgione”. It is more controversial how to explain the Hesperus/Phosphorus and 9/the number of planets examples. Frege’s own explanation of the former was to assimilate it to the “Hesperus”/“Phosphorus” case: in “It is informative to be told that Hesperus is Phosphorus” the names do not stand for their customary referent but for their senses. A Fregean explanation of the 9/number of planets example may also be offered: “it is necessary that” creates a context in which numerical designators stand for senses rather than numbers.

For present purposes the important point to recognise is that, however these counter-examples to the substitutivity principle are explained, they are not counter-examples to Leibniz’s Law, which says nothing about substitutivity of codesignators in any language.

The view of identity just put forward (henceforth “the classical view”) characterises it as the equivalence relation which everything has to itself and to nothing else and which satisfies Leibniz’s Law. These formal properties ensure that, within any theory expressible by means of a fixed stock of one- or many-place predicates, quantifiers and truth-functional connectives, any two predicates which can be regarded as expressing identity (i.e., any predicates satisfying the two schemata “for all x , Rxx ” and “for all x , for all y , Rxy → ( Fx → Fy )” for any one-place predicate in place of “ F ”) will be extensionally equivalent. They do not, however, ensure that any two-place predicate does express identity within a particular theory, for it may simply be that the descriptive resources of the theory are insufficiently rich to distinguish items between which the equivalence relation expressed by the predicate holds (“Identity” in Geach 1972).

Following Geach, call a two-place predicate with these properties in a theory an “I-predicate” in that theory. Relative to another, richer, theory the same predicate, interpreted in the same way, may not be an I-predicate. If so it will not, and did not even in the poorer theory, express identity. For example, “having the same income as” will be an I-predicate in a theory in which persons with the same income are indistinguishable, but not in a richer theory.

Quine (1950) has suggested that when a predicate is an I-predicate in a theory only because the language in which the theory is expressed does not allow one to distinguish items between which it holds, one can reinterpret the sentences of the theory so that the I-predicate in the newly interpreted theory does express identity. Every sentence will have just the same truth-conditions under the new interpretation and the old, but the references of its subsentential parts will be different. Thus, Quine suggests, if one has a language in which one speaks of persons and in which persons of the same income are indistinguishable the predicates of the language may be reinterpreted so that the predicate which previously expressed having the same income comes now to express identity. The universe of discourse now consists of income groups, not people. The extensions of the monadic predicates are classes of income groups, and, in general, the extension of an n -place predicate is a class of n -member sequences of income groups (Quine 1963: 65–79). Any two-place predicate expressing an equivalence relation could be an I-predicate relative to some sufficiently impoverished theory, and Quine’s suggestion will be applicable to any such predicate if it is applicable at all.

But it remains that it is not guaranteed that a two-place predicate that is an I-predicate in the theory to which it belongs expresses identity. In fact, no condition can be stated in a first-order language for a predicate to express identity, rather than mere indiscernibility by the resources of the language. However, in a second-order language, in which quantification over all properties (not just those for which the language contains predicates) is possible and Leibniz’s Law is therefore statable, identity can be uniquely characterised. Identity is thus not first-order, but only second-order definable.

This situation provides the basis for Geach’s radical contention that the notion of absolute identity has no application and that there is only relative identity. This section contains a brief discussion of Geach’s complex view. (For more details see the entry on relative identity , Deutsch 1997, Dummett 1981 and 1991, Hawthorne 2003 and Noonan 2017.) Geach maintains that since no criterion can be given by which a predicate expressing an I-predicate may be determined to express, not merely indiscernibility relative to the language to which it belongs, but also absolute indiscernibility, we should jettison the classical notion of identity (1991). He dismisses the possibility of defining identity in a second-order language on the ground of the paradoxical nature of unrestricted quantification over properties and aims his fire particularly at Quine’s proposal that an I-predicate in a first-order theory may always be interpreted as expressing absolute identity (even if such an interpretation is not required ). Geach objects that Quine’s suggestion leads to a “Baroque Meinongian ontology” and is inconsistent with Quine’s own expressed preference for “desert landscapes” (“Identity” in Geach 1972: 245).

We may usefully state Geach’s thesis using the terminology of absolute and relative equivalence relations. Let us say that an equivalence relation R is absolute if and only if, if x stands in it to y , there cannot be some other equivalence relation S , holding between anything and either x or y , but not holding between x and y . If an equivalence relation is not absolute it is relative. Classical identity is an absolute equivalence relation. Geach’s main contention is that any expression for an absolute equivalence relation in any possible language will have the null class as its extension, and so there can be no expression for classical identity in any possible language. This is the thesis he argues against Quine.

Geach also maintains the sortal relativity of identity statements, that “ x is the same A as y ” does not “split up” into “ x is an A and y is an A and x = y ”. More precisely stated, what Geach denies is that whenever a term “ A ” is interpretable as a sortal term in a language L (a term which makes (independent) sense following “the same”) the expression (interpretable as) “ x is the same A as y ” in language L will be satisfied by a pair < x , y > only if the I-predicate of L is satisfied by < x , y >. Geach’s thesis of the sortal relativity of identity thus neither entails nor is entailed by his thesis of the inexpressibility of identity. It is the sortal relativity thesis that is the central issue between Geach and Wiggins (1967 and 1980). It entails that a relation expressible in the form “ x is the same A as y ” in a language L , where “ A ” is a sortal term in L , need not entail indiscernibility even by the resources of L .

Geach’s argument against Quine exists in two versions, an earlier and a later.

In its earlier version the argument is merely that following Quine’s suggestion to interpret a language in which some expression is an I-predicate so that the I-predicate expresses classical identity sins against a highly intuitive methodological programme enunciated by Quine himself, namely that as our knowledge expands we should unhesitatingly expand our ideology, our stock of predicables, but should be much more wary about altering our ontology, the interpretation of our bound name variables (1972: 243).

Geach’s argument is that in view of the mere possibility of carving out of a language L , in which the relational expressions, E 1 , E 2 , E 3 … are not I-predicates, sub-languages L 1 , L 2 , L 3 … in which these expressions are I-predicates, if Quine’s suggested proposal of reinterpretation is possible for each L n , the user of L will be committed to any number of entities not quantified over in L , namely, for each L n , those entities for which the I-predicate of L n ( E n ) gives a criterion of absolute identity. This will be so because any sentence of L will retain its truth conditions in any L n to which it belongs, reinterpreted as Quine proposes, but “of course, it is flatly inconsistent to say that as a member of a large theory a sentence retains its truth-conditions but not its ontological commitment” (1973:299).

The crucial premiss of this argument is thus that sameness of truth-conditions entails sameness of ontological commitment. But this is not true. The ontological commitments of a theory (according to Quine, whose notion this is) are those entities that must lie within the domain of quantification of the theory if the theory is to be true; or, the entities the predicates of the theory have to be true of if the theory is to be true. A theory is not ontologically committed, we may say, to whatever has to be in the universe for it to be true, but only to whatever has to be in its universe for it to be true. Thus there is no argument from sameness of truth-conditions to sameness of ontological commitments.

The later version of Geach’s argument needs a different response. The difference between the earlier version and the later one is that in the later (to be found in Geach 1973) Geach’s claim is not merely that Quine’s thesis about possible reinterpretation has a consequence which is unpalatable, but that it leads to an out-and-out logical absurdity, the existence of what he calls “absolute surmen” (entities for which having the same surname constitutes a criterion of absolute identity, i.e., entails indiscernibility in all respects). Because Geach is now making this stronger claim, the objection that his argument depends upon the incorrect assumption that sameness of truth-conditions entails sameness of ontological commitment is no longer relevant. In order to make out his case Geach has to establish just two points. First, that there are sentences of English supplemented by the predicate “is the same surman as” (explained to mean “is a man and has the same surname as”), which are evidently true and which, considered as sentences of that fragment of English in which “is the same surman as” is an I-predicate, when this is interpreted in the way Quine suggests, can be true only if absolute surmen exist. And secondly, that the existence of absolute surmen is absurd.

But in the end Geach fails to establish these two points. Quine would say that, for the fragment of English in question, the domain of the variables can be considered to consist of classes of men with the same surname and the predicates interpreted as holding of such classes. Thus, the predicate “is the same surman as” will no longer be true of pairs of men if we adopt Quine’s suggestion (I am writing, remember in English, not in the fragment of English under discussion), but rather of pairs of classes of men with the same surname – these then will be Geach’s “absolute surmen”. Now, Geach attempts to rule this out by the argument that “whatever is a surman is by definition a man.” But this argument fails. The predicate “is a man” will also be in the language-fragment in which “is the same surman as” is the I-predicate; and so it, too, will, be reinterpreted, if we follow Quine’s suggestion, as holding of classes of men with the same surname. Thus the sentence “Whatever is a surman is a man” will be true in the language fragment interpreted in Quine’s way, just as it is in English as a whole. What will not be true, however, is that whatever the predicate “is a surman” is true of, as it occurs in the language-fragment reinterpreted in Quine’s way , is a thing of which “is a man”, as it occurs in English as a whole , is true of. But Geach has no right to demand that this should be the case. Even so, this demand can be met. For the domain of the interpretation of the language fragment in which “is the same surman as” is the I-predicate can, in fact, be taken to consist of men, namely, to be a class containing exactly one representative man for each class of men with the same surname. Thus, as Geach says, absolute surmen will be just some among men (1973, 100). Geach goes on, “there will, for example, be just one surman with the surname ‘Jones’, but if this is an absolute surman, and he is a certain man, then which of the Jones boys is he?” But this question, which is, of course, only answerable using predicates which belong to the part of English not included in the language fragment in which “is the same surman as” is the I-predicate, is not an impossible one to answer. It is merely that the answer will depend upon the particular interpretation that the language fragment has, in fact, been given. Geach is, therefore not entitled to go on, “Surely we have run into an absurdity.” It thus seems that his argument for the non-existence of absolute identity fails.

Geach’s argument for his second thesis, that of the sortal relativity of identity, is that it provides the best solution to a variety of well known puzzles about identity and counting at a time and over time. The most well known puzzle is that of the cat on the mat, which comes in two versions.

The first version goes like this. (Wiggins 1968 contains the first appearance of this version in present-day philosophical literature; an equivalent puzzle is that of Dion and Theon, see Burke 1995.) Suppose a cat, Tibbles, is sitting on a mat. Now consider that portion of Tibbles that includes everything except its tail – its “tail complement” – and call it “Tib”. Tib is smaller than Tibbles so they are not identical. But what if we now amputate the cat’s tail? (A time-reversed, or “growing”, version can be considered in which a tail is grafted on to a tailless cat; the same responses considered below will be available, but may differ in relative plausibility.) Tibbles and Tib will now coincide. If Tibbles is still a cat, it is hard to see by what criterion one could deny that Tib is a cat. Yet they are distinct individuals, since they have different histories. But there is just one cat on the mat. So they cannot be distinct cats. They must be the same cat, even though they are distinct individuals; and so identity under the sortal concept cat must be a relative identity relation.

The second version (presented in Geach 1980, compare Unger 1980) goes as follows. Tibbles is sitting on the mat and is the only cat sitting on the mat. But Tibbles has at least 1,000 hairs. Geach continues:

Now let c be the largest continuous mass of feline tissue on the mat. Then for any of our 1,000 cat-hairs, say h n , there is a proper part c n of c which contains precisely all of c except the hair h n ; and every such part c n differs in a describable way both from any other such part say c m , and from c as a whole. Moreover, fuzzy as the concept cat may be, it is clear that not only is c a cat, but also any part c n is a cat: c n would clearly be a cat were the hair h n to be plucked out, and we cannot reasonably suppose that plucking out a hair generates a cat, so c n must already have been a cat. (Geach 1980, 215)

The conclusion, of course, is the same as in the previous version of the argument: there is only one cat on the mat so all the distinct entities that qualify as cats must be the same cat.

This version of the argument can be resisted by insisting that the concept of a cat is maximal, i.e. no proper part of a cat is a cat. The first version may be resisted in a variety of ways. Some deny the existence of the tail-complement at all (van Inwagen 1981, Olson 1995); others deny that the tail-complement survives the amputation (Burke 1995). Another possibility is to say that certain of the historical and/or modal predicates possessed by Tibbles and not Tib are essential to being a cat, so that Tib is not (predicatively) a cat (Wiggins 1980). Again, it can be accepted that both Tib and Tibbles are cats, but deny that in counting them as one we are counting by identity, rather, we are counting by “almost identity” (Lewis 1993). Another possibility is to accept that both Tib and Tibbles are cats, but deny that they are distinct: rather “Tib” and “Tibbles” are two names of the same cat-stage (Hawley 2001, Sider 2001).

There is, then, no very compelling argument for Geach’s sortal relativity thesis to be based on such examples, given the variety of responses available, some of which will be returned to below. On the other hand, no alternative solution to the puzzle of the cat on the mat stands out as clearly superior to the rest, or clearly superior to the sortal relativity thesis as a solution. We should conclude that this component of Geach’s position, though not proven, is not refuted either, and, possibly, that the linguistic data provide no basis for a decision for or against.

A notion that Geach deploys extensively, and which is also in common use by his opponents, is that of a criterion of identity, a standard by which identity is to be judged. This section will attempt to untangle some of the complexities this notion involves.

The notion of a criterion of identity was introduced into philosophical terminology by Frege (1884) and strongly emphasised by Wittgenstein (1958). Exactly how it is to be interpreted and the extent of its applicability are still matters of debate.

A considerable obstacle to understanding contemporary philosophical usage of the term, however, is that the notion does not seem to be a unitary one. In the case of abstract objects (the case discussed by Frege) the criterion of identity for F s is thought of as an equivalence relation holding between objects distinct from F s. Thus the criterion of identity for directions is parallelism of lines , that is, the direction of line a is identical with the direction of line b if and only if line a is parallel to line b . The criterion of identity for numbers is equinumerosity of concepts , that is, the number of A s is identical with the number of B s if and only if there are exactly as many A s as B s. The relation between the criterion of identity for F s and the criterion of application for the concept F (the standard for the application of the concept to an individual) is then said by some (Wright and Hale 2001) to be that to be an F is just to be something for which questions of identity and distinctness are to settled by appeal to the criterion of identity for F s. (Thus, when Frege went on to give an explicit definition of numbers as extensions of concepts he appealed to it only to deduce what has come to be called Hume’s Principle – his statement of his criterion of identity for numbers in terms of equinumerosity of concepts, and emphasised that he regarded the appeal to extensions as inessential.) In the case of concrete objects, however, things seem to stand differently. Often the criterion of identity for a concrete object of type F is said to be a relation R such that for any F s, x and y , x = y if and only if Rxy . In this case the criterion of identity for F s is not stated as a relation between entities distinct from F s and the criterion of identity cannot plausibly be thought of as determining the criterion of application. Another example of the lack of uniformity in the notion of a criterion of identity in contemporary philosophy is, in the case of concrete objects, a distinction customarily made between a criterion of diachronic identity and a criterion of synchronic identity; the former taking the form “ x is at t the same F as y is at t ′ if and only if…”, where what fills the gap is some statement of a relation holding between objects x and y and times t and t ′. (In the case of persons, for example, a candidate criterion of diachronic identity is: x is at t the same person as y is at t ′ if and only if x at t is psychologically continuous with y at t ′.) A criterion of synchronic identity, by contrast, will typically specify how the parts of an F -thing existing at a time must be related, or how one F at a time is marked off from another.

One way of bringing system into the discussion of criteria of identity is to make use of the distinction between one-level and two-level criteria of identity (Williamson 1990, Lowe 2012). The Fregean criteria of identity for directions and numbers are two-level. The objects for which the criterion is given are distinct from, and can be pictured as at a higher level than, the entities between which the relation specified holds. A two-level criterion for the F s takes the form (restricting ourselves to examples in which the criterial relation holds between objects):

If x is a G and y is a G then d ( x ) = d ( y ) iff Rxy

e.g., If x and y are lines then the direction of x is identical with the direction of y iff x and y are parallel.

A two-level criterion of identity is thus in the first place an implicit definition of a function “ d ( )” (e.g., “the direction of”) in terms of which the sortal predicate “is an F ” can be defined (“is a direction” can be defined as “is the direction of some line”). Consistently with the two-level criterion of identity stated several distinct functions may be the reference of the functor “ d ”. Hence, as emphasised by Lowe (1997: section 6), two-level criteria of identity are neither definitions of identity, nor of identity restricted to a certain sort (for identity is universal), nor even of the sortal terms denoting the sorts for which they provide criteria. They merely constrain, but not to uniqueness, the possible referents of the functor “d” they implicitly define and they thus give a merely necessary condition for falling under the sortal predicate “is an F ” (where “ x is an F ” is explained to mean “for some y , x is identical with d ( y )”).

On the other hand, the criterion of identity for sets given by the Axiom of Extensionality (sets are the same iff they have the same members), unlike the criterion of identity for numbers given by Hume’s Principle, and Davidson’s criterion of event identity (events are the same iff they have the same causes and effects (“The Individuation of Events” in his 1980)) are one-level: the objects for which the criterion of identity is stated are the same as those between which the criterial relation obtains. In general, a one-level criterion for objects of sort F takes the form:

If x is an F and y is an F then x = y iff Rxy

Not all criteria of identity can be two-level (on pain of infinite regress), and it is tempting to think that the distinction between objects for which a two-level criterion is possible and those for which only a one-level criterion is possible coincides with that between abstract and concrete objects (and so, that a two-level criterion for sets must be possible).

However, a more general application of the two-level notion is possible. In fact, it can be applied to any type of object K , such that the criterion of identity for K s can be thought of as an equivalence relation between a distinct type of object, K *s, but some such objects may intuitively be regarded as concrete.

How general this makes its application is a matter of controversy. In particular, if persisting things are thought of as composed of (instantaneous) temporal parts (see discussion below), the problem of supplying a diachronic criterion of identity for persisting concrete objects can be regarded as the problem of providing a two-level criterion. But if persisting things are not thought of in this way then not all persisting things can be provided with two-level criteria. (Though some can. For example, it is quite plausible that the criterion of identity over time for persons should be thought of as given by a relation between bodies.)

As noted by Lowe (1997) and Wright and Hale (2001) any two-level criterion can be restated in a one-level form (though, of course, not conversely). For example, to say that the direction of line a is identical with the direction of line b if and only if line a is parallel to line b is to say that directions are the same if and only if the lines they are of are parallel, which is the form of a one-level criterion. A way of unifying the various different ways of talking of criteria of identity is thus to take as the paradigmatic form of a statement of a criterion of identity a statement of the form: for any x , for any y , if x is an F and y is an F then x = y if and only if Rxy (Lowe 1989, 1997).

If the notion is interpreted in this way then the relation between the criterion of identity and the criterion of application will be that of one-way determination. The criterion of identity will be determined by, but not determine, the criterion of application.

For, in general, a one-level criterion of identity for F s as explained above is equivalent to the conjunction of:

If x is an F then Rxx

If x is an F then if y is an F and Rxy then x = y

Each of these gives a merely necessary condition for being an F . And the second says something about F s which is not true of everything only if “ Rxy ” does not entail “ x = y ”

Together these are equivalent to the proposition that every F is the F “ R -related” to it. By its form this states a merely necessary condition for being a thing of sort “ F ”. The one-level criterion of identity thus again merely specifies a necessary condition of being an object of sort “ F ”.

Hence, once the necessary and sufficient conditions of being an “ F ” are laid down, no further stipulation is required of a criterion of “ F ”-identity, whether one-level or two-level.

This conclusion is, of course, in agreement with Lewis’s view that there are no genuine problems about identity as such (Lewis 1986, Ch. 4), but it is in tension with the thought that sortal concepts, as distinct from adjectival concepts, are to be characterised by their involvement of criteria of identity as well as criteria of application.

A conception of identity criteria which allows this characterisation of the notion of a sortal concept, and which has so far not been mentioned, is that of Dummett (1981). Dummett denies that a criterion of identity must always be regarded as a criterion of identity for a type of object . There is a basic level, he suggests, at which what a criterion of identity is a criterion of, is the truth of a statement in which no objects are referred to. Such a statement can be expressed using demonstratives and pointing gestures, for instance, by saying “This is the same cat as that”, pointing first to a head and then a tail. In such a statement, which he calls a statement of identification, in Dummett’s view, there need be no reference to objects made by the use of the demonstratives, any more than reference is made to any object in a feature-placing sentence like “It’s hot here”. A statement of identification is merely, as it were, a feature-placing relational statement, like “This is darker than that”. A grasp of a sortal concept F involves both grasp of the truth-conditions of such statements of identification involving “ F ” and also grasp of the truth-conditions of what Dummett calls “crude predications” involving “ F ”, statements of the form “this is F ”, in which the demonstrative again does not serve to refer to any object. Adjectival terms, which have only a criterion of application and no criterion of identity, are ones which have a use in such crude predications, but no use in statements of identification. Sortal terms, as just noted, have a use in both contexts, and sortal terms may share their criteria of application but differ in their criteria of identity since grasp of the truth-conditions of the crude predication “This is F ” does not determine grasp of the truth-conditions of the statement of identification “This is the same F as that” (thus I can know when it is right to say “This is a book” without knowing when it is right to say “This is the same book as that”).

On Dummett’s account, then, it may be possible to accept that whenever a criterion of identity for a type of object is to be given it must be (expressible as) a two-level criterion, which implicitly defines a functor. Essentially one-level criteria (one-level criteria not expressible in a two-level form) are redundant, determined by specifications of necessary and sufficient conditions for being objects of the sorts in question.

As noted in the last section, another source of apparent disunity in the concept of a criterion of identity is the distinction made between synchronic criteria of identity and diachronic criteria of identity. Criteria of identity can be employed synchronically, as in the examples just given, to determine whether two coexistent objects are parts of the same object of a sort, or diachronically, to determine identity over time. But as Lowe notes (2012: 137), it is an error to suppose that diachronic identity and synchronic identity are different kinds of identity and so demand different kinds of identity criteria. What then is a criterion of identity over time?

Identity over time is itself a controversial notion, however, because time involves change. Heraclitus argued that one could not bathe in the same river twice because new waters were ever flowing in. Hume argued that identity over time was a fiction we substitute for a collection of related objects. Such views can be seen as based on a misunderstanding of Leibniz’s Law: if a thing changes something is true of it at the later time that is not true of it at the earlier, so it is not the same. The answer is that what is true of it at the later time is, say, “being muddy at the later time”, which was always true of it; similarly, what is true of it at the earlier time, suitably expressed, remains true of it. But the question remains how to characterise identity through time and across change given that there is such a thing.

One topic which has always loomed large in this debate has been the issue (in the terminology of Lewis 1986, Ch. 4) of perdurance versus endurance . (Others, for which there is no space for discussion here, include the debate over Ship of Theseus and reduplication or fission problems and associated issues about “best candidate” or “no rival candidate” accounts of identity over time, and the debate over Humean supervenience – see articles on relative identity, personal identity, Hawley 2001 and Sider 2001.)

According to one view, material objects persist by having temporal parts or stages, which exist at different times and are to be distinguished by the times at which they exist – this is known as the view that material objects perdure. Other philosophers deny that this is so; according to them, when a material object exists at different times, it is wholly present at those times, for it has no temporal parts, but only spatial parts, which likewise are wholly present at the different times they exist. This is known as the view that material objects endure.

Perdurance theorists, as Quine puts it, reject the point of view inherent in the tenses of our natural language. From that point of view persisting things endure and change through time, but do not extend through time, but only through space. Thus persisting things are to be sharply distinguished from events or processes, which precisely do extend through time. One way of describing the position of the perdurance theorist, then, is to say that he denies the existence of a distinct ontological category of persisting things , or substances. Thus, Quine writes, “physical objects, conceived thus four-dimensionally in space-time, are not to be distinguished from events, or, in the concrete sense of the term, processes. Each comprises simply the content, however heterogeneous, of some portion of space-time, however disconnected and gerrymandered” (1960:171).

In recent controversy two arguments have been at the centre of the endurance/perdurance debate, one employed by perdurance theorists and the other by endurance theorists (for other arguments and issues see the separate article on temporal parts, Hawley 2001 and Sider 2001).

An argument for perdurance which has been hotly debated is due to David Lewis (1986). If perdurance is rejected, the ascription of dated or tensed properties to objects must be regarded as assertions of irreducible relations between objects and times. If Tabby is fat on Monday, that is a relation between Tabby and Monday, and if perdurance is rejected it is an irreducible relation between Tabby and Monday. According to perdurance theory, however, while it is still, of course, a relation between Tabby and Monday it is not irreducible; it holds between Tabby and Monday because the temporal part of Tabby on Monday, Tabby-on-Monday, is intrinsically fat. If perdurance is rejected, however, no such intrinsic possessor of the property of fatness can be recognised: Tabby’s fatness on Monday must be regarded as an irreducible state of affairs.

According to Lewis, this consequence of the rejection of the perdurance theory is incredible. Whether he is right about this is the subject of intense debate (Haslanger 2003).

Even if Lewis is right, however, the perdurance theory may still be found wanting, since it does not secure the most commonsensical position: that fatness is a property of a cat (Haslanger 2003). According to perdurance theory, rather, it is a property of a (temporal) cat part. Those known as stage theorists (Hawley 2001, Sider 2001), accepting the ontology of perdurance theory, but modifying its semantics, offer a way to secure this desirable result. Every temporal part of a cat is a cat, they say, so Tabby-on-Monday (which is what we refer to by “Tabby”, on Monday) is a cat and is fat, just as we would like. Stage theorists have to pay a price for this advantage over perdurance theory, however. For they must accept either that our reports of the cross-temporal number of cats are not always reports of the counting of cats (as when I say, truly, that I have only ever owned three cats) or that two cat-stages (cats) may be counted as one and the same cat, so that counting cats is not always counting in accordance with absolute identity.

An argument against the perdurance theory that has been the focus of interest is one presented in various guises by a number of writers, including Wiggins (1980), Thomson (1983) and van Inwagen (1990). Applied to persons (it can equally well be applied to other persisting things), it asserts that persons have different properties, in particular, different modal properties, from the summations of person-stages with which the perdurance theory identifies them. Thus, by Leibniz’s Law, this identification must be mistaken. As David Wiggins states the argument: “Anything that is a part of a Lesniewskian sum [a mereological whole defined by its parts] is necessarily part of it…But no person or normal material object is necessarily in the total state that will correspond to the person- or object-moment postulated by the theory under discussion” (1980: 168).

To elaborate a little. I might have died when I was five years old. But that maximal summation of person-stages which, according to perdurance theory, is me and has a temporal extent of at least fifty years, could not have had a temporal extent of a mere five years. So I cannot be such a summation of stages.

This argument illustrates the interdependence of the various topics discussed under the rubric of identity. Whether it is valid, of course, depends on the correct analysis of modal predication, and, in particular, on whether it should be analysed in terms of “identity across possible worlds” or in terms of Lewisian counterpart theory. This is the topic of the next section.

In the interpretation of modal discourse recourse is often made to the idea of “identity across possible worlds”. If modal discourse is interpreted in this way it becomes natural to regard a statement ascribing a modal property to an individual as asserting the identity of that individual across worlds: “Sarah might have been a millionaire”, on this view, asserts that there is a possible world in which an individual identical with Sarah is a millionaire. “Sarah could not have been a millionaire” asserts that in any world in which an individual identical with Sarah exists that individual is not a millionaire.

However, though this is perhaps the most natural way to interpret de re modal statements (once it has been accepted that the apparatus of possible worlds is to be used as an interpretative tool), there are well-known difficulties that make the approach problematic.

For example, it seems reasonable to suppose that a complex artefact like a bicycle could have been made of different parts. On the other hand, it does not seem right that the same bicycle could have been constructed out of completely different parts.

But now consider a series of possible worlds, beginning with the actual world, each containing a bicycle just slightly different from the one in the previous world, the last world in the sequence being one in which there is a bicycle composed of completely different parts from the one in the actual world. One cannot say that each bicycle is identical with the one in the neighbouring world, but not identical with the corresponding bicycle in distant worlds, since identity is transitive. Hence it seems one must either adopt an extreme mereological essentialism, according to which no difference of parts is possible for an individual, or reject the interpretation of de re modal discourse as asserting identity across possible worlds.

This and other problems with cross-world identity suggest that some other weaker relation, of similarity or what David Lewis calls counterparthood, should be employed in a possible world analysis of modal discourse. Since similarity is not transitive this allows us to say that the bicycle might have had some different parts without having to say that it might have been wholly different. On the other hand, such a substitution does not seem unproblematic, for a claim about what I might have done hardly seems, at first sight, to be correctly interpretable as a claim about what someone else (however similar to me) does in another possible world (Kripke 1972 [1980], note 13).

An assessment of the counterpart theoretic analysis is vital not just to understanding modal discourse, however, but also to getting to the correct account of identity over time. For, as we saw, the argument against perdurance theory outlined at the end of the last section depends on the correct interpretation of modal discourse. In fact, it is invalid on a counterpart theoretic analysis which allows different counterpart relations (different similarity relations) to be invoked according to the sense of the singular term which is the subject of the de re modal predication (Lewis 1986, Ch. 4), since the counterpart relation relevant to the assessment of a de re modal predication with a singular term whose sense determines that it refers to a person will be different from that relevant to the assessment of a de re modal predication with a singular term whose sense determines that it refers to a sum of person-stages. “I might have existed for only five years” means on the Lewisian account “There is a person in some possible world similar to me in those respects important to personhood who exists for only five years”; “The maximal summation of person stages of which this current stage is a stage might have existed for only five years” means “There is a summation of person stages similar to this one in those respects important to the status of an entity as a summation of stages which exists for only five years”. Since the two similarity relations in question are distinct the first modal statement may be true and the second false even if I am identical with the sum of stages in question.

Counterpart theory is also significant to the topic of identity over time in another way, since it provides the analogy to which the stage theorist (who regards all everyday reference as reference to momentary stages rather than to perdurers) appeals to explain de re temporal predication. Thus, according to the stage theorist, just as “I might have been fat” does not require the existence of a possible world in which an object identical with me is fat, but only the existence of a world in which a (modal) counterpart of me is fat, so “I used to be fat” does not require the existence of a past time at which someone identical with (the present momentary stage which is) me was fat, but only the existence of a past time at which a (temporal) counterpart of me was fat. The problem of identity over time for things of a kind, for stage theorists, is just the problem of characterizing the appropriate temporal counterpart relation for things of that kind.

For a more detailed discussion of the topic, see the entry transworld identity . Whether de re modal discourse is to be interpreted in terms of identity across possible worlds or counterpart theoretically (or in some other way entirely) is also relevant to our next topic, that of contingent identity.

Before Kripke’s writings (1972 [1980]), it seemed a platitude that statements of identity could be contingent – when they contained two terms differing in sense but identical in reference and so were not analytic. Kripke challenged this platitude, though, of course, he did not reject the possibility of contingent statements of identity. But he argued that when the terms flanking the sign of identity were what he called rigid designators, an identity statement, if true at all, had to be necessarily true, but need not be knowable a priori , as an analytic truth would be. Connectedly, Kripke argued that identity and distinctness were themselves necessary relations: if an object is identical with itself it is necessarily so, and if it is distinct from another it is necessarily so.

Kripke’s arguments were very persuasive, but there are examples that suggest that his conclusion is too sweeping – that even identity statements containing rigid designators can be, in a sense, contingent. The debate over contingent identity is concerned with the assessment and proper analysis of these examples.

One of the earliest examples is provided by Gibbard (1975). Consider a statue, Goliath, and the clay, Lumpl, from which it is composed. Imagine that Lumpl and Goliath coincide in their spatiotemporal extent. It is tempting to conclude that they are identical. But they might not have been. Goliath might have been rolled into a ball and destroyed; Lumpl would have continued to exist. The two would have been distinct. Thus it seems that the identity of Lumpl and Goliath, if admitted, must be acknowledged as merely contingent.

One reaction to this argument available to the convinced Kripkean is simply to deny that Lumpl and Goliath are identical. But to accept this is to accept that purely material entities, like statues and lumps of clay, of admittedly identical material constitution at all times, may nonetheless be distinct, though distinguished only by modal, dispositional or counterfactual properties. To many, however, this seems highly implausible, which provides the strength of the argument for contingent identity. Another way of thinking of this matter is in terms of the failure of the supervenience of the macroscopic on the microscopic. If Lumpl is distinct from Goliath then a far distant duplicate of Lumpl, Lumpl*, coincident with a statue Goliath*, though numerically distinct from Goliath will be microscopically indistinguishable from Goliath in all general respects, relational as well as non-relational, past and future as well as present, even modal and dispositional as well as categorical, but will be macroscopically distinguishable in general respects, since it will not be a statue, and will have modal properties, such as the capacity to survive radical deformation in shape, which no statue possesses.

David Lewis (in “Counterparts of Persons and their Bodies”, 1971) suggests that the identity of a person with his body (assuming the person and the body, like Goliath and Lumpl, are at all times coincident) is contingent, since bodily interchange is a possibility. He appeals to counterpart theory, modified to allow a variety of counterpart relations, to explain this. Contingent identity then makes sense, since “I and my body might not have been identical” now translates into counterpart theory as “There is a possible world, w , a unique personal counterpart x in w of me and a unique bodily counterpart y in w of my body, such that x and y are not identical”.

What is crucial to making sense of contingent identity is an acceptance that modal predicates are inconstant in denotation (that is, stand for different properties when attached to different singular terms or different quantifying expressions). Counterpart theory provides one way of explaining this inconstancy, but is not necessarily the only way (Gibbard 1975, Noonan 1991, 1993). However, whether the examples of contingent identity in the literature are persuasive enough to make it reasonable to accept the certainly initially surprising idea that modal predications are inconstant in denotation is still a matter of considerable controversy.

Finally, in this section, it is worth noting explicitly the interdependence of the topics under discussion: only if the possibility of contingent identity is secured, by counterpart theory or some other account of de re modality which does not straightforwardly analyse de re modal predication in terms of identity across possible worlds, can perdurance theory (or stage theory) as an account of identity across time be sustained against the modal arguments of Wiggins, Thomson and van Inwagen.

A thesis that has a long pedigree but has only recently been gathering attention in the contemporary literature is the “Composition as Identity” thesis. The thesis comes in a weak and a strong form. In its weak form the thesis is that the mereological composition relation is analogous in a number of important ways to the identity relation and so deserves to be called a kind of identity. In its strong form the thesis is that the composition relation is strictly identical with the identity relation, viz. that the parts of a whole are literally (collectively) identical with the whole itself. The strong thesis was considered by Plato in Parmenides and versions of the thesis have been discussed by many historical figures since (Harte 2002, Normore and Brown 2014). The progenitor of the modern version of the thesis is Baxter (1988a, 1988b, 2001) but it is most often discussed under the formulation of it given by Lewis (1991), who first considers the strong thesis before rejecting it in favour of the weak thesis.

Both the strong and the weak versions of the thesis are motivated by the fact that there is an especially intimate relation between a whole and its parts (a whole is “nothing over and above” its parts), buttressed by claims that identity and composition are alike in various ways. Lewis (1991: 85) makes five likeness claims:

- Ontological Innocence. If one believes that some object x exists, one does not gain a commitment to a further object by believing that something identical with x exists. Likewise, if one believes that some objects x 1 , x 2 , …, x n exist, one does not gain a commitment to a further object by claiming that something composed of x 1 , x 2 , …, x n exists.

- Automatic Existence. If some object x exists, then it automatically follows that something identical with x exists. Likewise, if some objects x 1 , x 2 , …, x n exist, then it automatically follows that something composed of x 1 , x 2 , …, x n exists.

- Unique Composition. If something y is identical with x , then anything identical with x is identical with y , and anything identical with y is identical with x . Likewise, if some things y 1 , y 2 , …, y n compose x , then any things that compose x are identical with y 1 , y 2 , …, y n , and anything identical with x is composed of y 1 , y 2 , …, y n .

- Exhaustive Description. If y is identical with x , then an exhaustive description of y is an exhaustive description of x , and vice versa. Likewise, if y 1 , y 2 , …, y n compose x , then an exhaustive description of y 1 , y 2 , …, y n is an exhaustive description of x , and vice versa.

- Same Location. If y is identical with x , then necessarily, x and y fill the same region of spacetime. Likewise, if y 1 , y 2 , …, y n compose x , then necessarily, y 1 , y 2 , …, y n and x fill the same region of spacetime.

Clearly not all will agree with each of Lewis’s likeness claims. Anyone who denies unrestricted mereological composition, for example, will deny 2. And the defender of strong pluralism in the material constitution debate (i.e. one who defends the view that there can be all-time coincident entities) will deny 3. And some endurantists who think that ordinary material objects can have distinct parts at distinct times will deny 5. But there is a more general problem with 1, as van Inwagen has made clear (1994: 213). Consider a world w1 that contains just two simples s1 and s2. Now consider the difference between someone p1 who believes that s1 and s2 compose something and someone p2 who does not. Ask: how many objects do p1 and p2 believe there to be in w1? The answer, it seems, is that p1 believes that there are three things and p2 only two. So how can a commitment to the existence of fusions be ontologically innocent? One recent suggestion is that although a commitment to the existence of fusions is not ontologically innocent, it almost is: to commit oneself to fusions is to commit oneself to further entities, but because they are not fundamental entities they are not ones that matter for the purpose of theory choice (Cameron 2014, Schaffer 2008, Williams 2010, and see also Hawley 2014).

If one believes Lewis’s likeness claims one will be tempted by at least the weak Composition as Identity thesis. If composition is a type of identity this gives some kind of explanation of why the parallels between the two hold. But the strong thesis, that the composition relation is the identity relation, gives a fuller explanation. So why not hold the strong thesis? Because, many think, there are additional challenges that face anyone who wishes to defend the strong thesis.

The classical identity relation is one that can only have single objects as relata (as in: “Billie Holiday = Eleanora Fagan”). If we adopt a language that allows the formation of plural terms we can unproblematically define a plural identity relation that holds between pluralities of objects too. Plural identity statements such as “the hunters are identical with the gatherers” are understood to mean that for all x , x is one of the hunters iff x is one of the gatherers. But, according to the strong Composition as Identity thesis, there can also be true hybrid identity statements that relate pluralities and single objects. That is, sentences such as “the bricks = the wall” are taken by the defender of strong Composition as Identity to be well-formed sentences that express strict identities.

The first challenge facing the defender of the strong thesis is the least troublesome. It is the syntactic problem that hybrid identity statements are ungrammatical in English (Van Inwagen, 1994: 211). Whilst “Billie Holiday is identical with Eleanora Fagan” and “the hunters are identical with the gatherers” are well-formed, it seems that “the bricks are identical with the wall” is not. However, there is in fact some doubt about whether hybrid identity statements are ungrammatical in English, and some have pointed out that this is anyway a mere grammatical artefact of English that is not present in other languages (e.g. Norwegian and Hungarian). So it seems that the most this challenge calls for is a mild form of grammatical revisionism. And we have, at any rate, formal languages that allow hybrid constructions to be made in which to express the claims made by the defender of the strong Composition as Identity thesis. (Sider 2007, Cotnoir 2013) (NB The claims regarding Norwegian and Hungarian are to be found in these two papers.)

The second challenge is more troublesome. It is the semantic problem of providing coherent truth-conditions for hybrid identity statements. The standard way to provide the truth-conditions for the classical identity relation is to say that an identity statement of the form “ a = b ” is true iff “ a ” and “ b ” have the same referents. But this account clearly does not work for hybrid identity statements, for there is no (single) referent for a plural term. Moreover, the standard way of giving the truth-conditions for plural identity statements (mentioned above) does not work for hybrid identity statements either. To say that “ x is one of the y s” is to say that x is (classically) identical with one of the things in the plurality, i.e., that x is identical with y 1 , or identical with y 2 … or identical with y n . But then “the bricks = the wall” is true only if the wall is (classically) identical with one of the bricks, i.e. with b 1 , or with b 2 … or with b n , which it isn’t.

The third challenge is the most troublesome of all. In section 2 it was noted that Leibniz’s Law (and its contrapositive) appear to be crucial to our understanding of identity and distinctness. But it seems that the defender of strong Composition as Identity must deny this. After all, the bricks are many, but the wall is one. The onus is thus on the defender of strong Composition as Identity to explain why we should think the “are” in hybrid identity statements really expresses the relation of identity.

The second and the third challenges have been thought by many to be insurmountable (Lewis, for example, rejects strong Composition as Identity on the basis of them). But, in recent semantic work in this area, accounts have emerged that promise to answer both challenges. (Wallace 2011a, 2011b, Cotnoir 2013). Whether they do so, however, remains to be seen.

Like the impossibility of contingent identity, the impossibility of vague identity appears to be a straightforward consequence of the classical concept of identity (Evans 1978, see also Salmon 1982). For if a is only vaguely identical with b , something is true of it – that it is only vaguely identical with b – that is not true of b , so, by Leibniz’s Law, it is not identical with b at all. Of course, there are vague statements of identity – “Princeton is Princeton Borough” (Lewis 1988) – but the conclusion appears to follow that such vagueness is only possible when one or both of the terms flanking the sign of identity is an imprecise designator. Relatedly, it appears to follow that identity itself must be a determinate relation.

But some examples suggest that this conclusion is too sweeping – that even identity statements containing precise designators may be, in some sense, indeterminate. Consider Everest and some precisely defined hunk of rock, ice and snow, Rock, of which it is indeterminate whether its boundaries coincide with those of Everest. It is tempting to think that “Everest” and “Rock” are both precise designators (if “Everest” is not, is anything? (Tye 2000)) and that “Everest is Rock” is nonetheless in some sense indeterminate.

Those who take this view have to respond to Evans’s original argument, about which there has been intense debate (see separate article on vagueness, Edgington 2000, Lewis 1988, Parsons 2000, van Inwagen 1990, Williamson 2002 and 2003), but also to more recent variants. There is no space to go into these matters here, but one particular variant of the Evans argument worth briefly noting is given by Hawley (2001). Alpha and Omega are (two?) people, the first of whom steps into van Inwagen’s (1990) fiendish cabinet which disrupts whatever features are relevant to personal identity, and the second of whom then steps out:

(1) It is indeterminate whether Alpha steps out of the cabinet (2) Alpha is such that it is indeterminate whether she steps out of the cabinet (3) It is not indeterminate whether Omega steps out of the cabinet (4) Omega is not such that it is indeterminate whether she steps out of the cabinet (5) Alpha is not identical to Omega.

This argument differs from the standard version of Evans’s argument by not depending upon identity-involving properties (e.g. being such that it is indeterminate whether she is Omega) to establish distinctness, and this removes some sources of controversy. Others, of course, remain.

The debate over vague identity is too vast to survey here, but to finish this section we can relate this debate to the previously discussed debate about identity over time.

For some putative cases of vagueness in synchronic identity it seems reasonable to accept the conclusion of Evans’s argument and locate the indeterminacy in language (see the “Reply” by Shoemaker in Shoemaker and Swinburne 1984 for the following example). A structure consists of two halls, Alpha Hall and Beta Hall, linked by a flimsy walkway, Smith is located in Alpha Hall, Jones in Beta Hall. The nature of the structure is such that the identity statement “The building in which Smith is located is the building in which Jones is located” is neither true nor false because it is indeterminate whether Alpha Hall and Beta Hall count as two distinct buildings or merely as two parts of one and the same building. Here it is absolutely clear what is going on. The term “building” is vague in a way that makes it indeterminate whether it applies to the whole structure or just to the two halls. Consequently, it is indeterminate what “the building in which Smith is located” and “the building in which Jones is located” denote.

Perdurance theorists, who assimilate identity over time to identity over space, can accommodate vagueness in identity over time in the same way. In Hawley’s example they can say that there are several entities present: one that exists before and after the identity-obscuring occurrences in the cabinet, one that exists only before, and one that exists only after. It is indeterminate which of these is a person and so it is indeterminate what the singular terms “Alpha” and “Omega” refer to.

This involves taking on an ontology that is larger than we ordinarily recognise, but that is not uncongenial to the perdurance theorist, who is happy to regard any, however spatiotemporally disconnected, region as containing a physical object (Quine 1960:171).

But what of endurance theorists?

One option for them is to adopt the same response and to accept a multiplicity of entities partially coinciding in space and time where to common sense there seems to be only one. But this is to give up on one of the major advantages claimed by the endurance theorist, his consonance with common sense.

The endurance theorist has several other options. He may simply deny the existence of the relevant entities and restrict his ontology to entities which are not complex; he may insist that any change destroys identity so that in a strict and philosophical sense Alpha is distinct from Omega; or he may reject the case as one of vagueness, insisting that, though we do not know the answer, either Alpha is Omega or she is not.

However, the most tempting option for the endurance theorist, which keeps closest to common sense, is to accept that the case is one of vagueness, deny the multiplicity of entities embraced by the perdurance theorist and reject Evans’s argument against vague identity.

That this is so highlights the fact that there is no easy solution to the problem consonant in every respect with common sense. Locating the vagueness in language requires us to acknowledge a multiplicity of entities of which we would apparently otherwise have to take no notice. Whilst locating it in the world requires an explanation of how, contrary to Evans’s argument, the impossibility of vague identity is not a straightforward consequence of the classical conception of identity, or else the abandonment of that conception.

Finally in this entry we return briefly to the idea mentioned in the introduction that although the debates about identity make sense they cannot genuinely be debates about identity, since there are no philosophical problems about identity. This view has recently been receiving increasing attention. Lewis is the most cited defender of this view. In the context of discussing the putative “problem” of trans-world identity he says:

[W]e should not suppose that we have here any problem about identity . We never have. Identity is utterly simple and unproblematic. Everything is identical to itself; nothing is ever identical to anything except itself. There is never any problem about what makes something identical to itself; nothing can ever fail to be. (Lewis 1986: 192–93)