- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Non-Medical Databases

- Study Resources

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Population Health

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Give to the Library

- What is a Systematic Review?

Types of Reviews

- Manuals and Reporting Guidelines

- Our Service

- 1. Assemble Your Team

- 2. Develop a Research Question

- 3. Write and Register a Protocol

- 4. Search the Evidence

- 5. Screen Results

- 6. Assess for Quality and Bias

- 7. Extract the Data

- 8. Write the Review

- Additional Resources

- Finding Full-Text Articles

Review Typologies

There are many types of evidence synthesis projects, including systematic reviews as well as others. The selection of review type is wholly dependent on the research question. Not all research questions are well-suited for systematic reviews.

- Review Typologies (from LITR-EX) This site explores different review methodologies such as, systematic, scoping, realist, narrative, state of the art, meta-ethnography, critical, and integrative reviews. The LITR-EX site has a health professions education focus, but the advice and information is widely applicable.

Review the table to peruse review types and associated methodologies. Librarians can also help your team determine which review type might be appropriate for your project.

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91-108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review?

- Next: Manuals and Reporting Guidelines >>

- Last Updated: Dec 13, 2024 10:51 AM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

An overview of methodological approaches in systematic reviews

Prabhakar veginadu, hanny calache, akshaya pandian, mohd masood.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence , Dr. Prabhakar Veginadu, Department of Rural Clinical Sciences, La Trobe University, PO Box 199, Bendigo, Victoria 3552, Australia. Email: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2021 Aug 8; Accepted 2022 Mar 18; Issue date 2022 Mar.

This is an open access article under the terms of the http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and is not used for commercial purposes.

The aim of this overview is to identify and collate evidence from existing published systematic review (SR) articles evaluating various methodological approaches used at each stage of an SR.

The search was conducted in five electronic databases from inception to November 2020 and updated in February 2022: MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and APA PsycINFO. Title and abstract screening were performed in two stages by one reviewer, supported by a second reviewer. Full‐text screening, data extraction, and quality appraisal were performed by two reviewers independently. The quality of the included SRs was assessed using the AMSTAR 2 checklist.

The search retrieved 41,556 unique citations, of which 9 SRs were deemed eligible for inclusion in final synthesis. Included SRs evaluated 24 unique methodological approaches used for defining the review scope and eligibility, literature search, screening, data extraction, and quality appraisal in the SR process. Limited evidence supports the following (a) searching multiple resources (electronic databases, handsearching, and reference lists) to identify relevant literature; (b) excluding non‐English, gray, and unpublished literature, and (c) use of text‐mining approaches during title and abstract screening.

The overview identified limited SR‐level evidence on various methodological approaches currently employed during five of the seven fundamental steps in the SR process, as well as some methodological modifications currently used in expedited SRs. Overall, findings of this overview highlight the dearth of published SRs focused on SR methodologies and this warrants future work in this area.

Keywords: knowledge synthesis, methodology, overview, systematic reviews

1. INTRODUCTION

Evidence synthesis is a prerequisite for knowledge translation. 1 A well conducted systematic review (SR), often in conjunction with meta‐analyses (MA) when appropriate, is considered the “gold standard” of methods for synthesizing evidence related to a topic of interest. 2 The central strength of an SR is the transparency of the methods used to systematically search, appraise, and synthesize the available evidence. 3 Several guidelines, developed by various organizations, are available for the conduct of an SR; 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 among these, Cochrane is considered a pioneer in developing rigorous and highly structured methodology for the conduct of SRs. 8 The guidelines developed by these organizations outline seven fundamental steps required in SR process: defining the scope of the review and eligibility criteria, literature searching and retrieval, selecting eligible studies, extracting relevant data, assessing risk of bias (RoB) in included studies, synthesizing results, and assessing certainty of evidence (CoE) and presenting findings. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7

The methodological rigor involved in an SR can require a significant amount of time and resource, which may not always be available. 9 As a result, there has been a proliferation of modifications made to the traditional SR process, such as refining, shortening, bypassing, or omitting one or more steps, 10 , 11 for example, limits on the number and type of databases searched, limits on publication date, language, and types of studies included, and limiting to one reviewer for screening and selection of studies, as opposed to two or more reviewers. 10 , 11 These methodological modifications are made to accommodate the needs of and resource constraints of the reviewers and stakeholders (e.g., organizations, policymakers, health care professionals, and other knowledge users). While such modifications are considered time and resource efficient, they may introduce bias in the review process reducing their usefulness. 5

Substantial research has been conducted examining various approaches used in the standardized SR methodology and their impact on the validity of SR results. There are a number of published reviews examining the approaches or modifications corresponding to single 12 , 13 or multiple steps 14 involved in an SR. However, there is yet to be a comprehensive summary of the SR‐level evidence for all the seven fundamental steps in an SR. Such a holistic evidence synthesis will provide an empirical basis to confirm the validity of current accepted practices in the conduct of SRs. Furthermore, sometimes there is a balance that needs to be achieved between the resource availability and the need to synthesize the evidence in the best way possible, given the constraints. This evidence base will also inform the choice of modifications to be made to the SR methods, as well as the potential impact of these modifications on the SR results. An overview is considered the choice of approach for summarizing existing evidence on a broad topic, directing the reader to evidence, or highlighting the gaps in evidence, where the evidence is derived exclusively from SRs. 15 Therefore, for this review, an overview approach was used to (a) identify and collate evidence from existing published SR articles evaluating various methodological approaches employed in each of the seven fundamental steps of an SR and (b) highlight both the gaps in the current research and the potential areas for future research on the methods employed in SRs.

An a priori protocol was developed for this overview but was not registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), as the review was primarily methodological in nature and did not meet PROSPERO eligibility criteria for registration. The protocol is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. This overview was conducted based on the guidelines for the conduct of overviews as outlined in The Cochrane Handbook. 15 Reporting followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) statement. 3

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Only published SRs, with or without associated MA, were included in this overview. We adopted the defining characteristics of SRs from The Cochrane Handbook. 5 According to The Cochrane Handbook, a review was considered systematic if it satisfied the following criteria: (a) clearly states the objectives and eligibility criteria for study inclusion; (b) provides reproducible methodology; (c) includes a systematic search to identify all eligible studies; (d) reports assessment of validity of findings of included studies (e.g., RoB assessment of the included studies); (e) systematically presents all the characteristics or findings of the included studies. 5 Reviews that did not meet all of the above criteria were not considered a SR for this study and were excluded. MA‐only articles were included if it was mentioned that the MA was based on an SR.

SRs and/or MA of primary studies evaluating methodological approaches used in defining review scope and study eligibility, literature search, study selection, data extraction, RoB assessment, data synthesis, and CoE assessment and reporting were included. The methodological approaches examined in these SRs and/or MA can also be related to the substeps or elements of these steps; for example, applying limits on date or type of publication are the elements of literature search. Included SRs examined or compared various aspects of a method or methods, and the associated factors, including but not limited to: precision or effectiveness; accuracy or reliability; impact on the SR and/or MA results; reproducibility of an SR steps or bias occurred; time and/or resource efficiency. SRs assessing the methodological quality of SRs (e.g., adherence to reporting guidelines), evaluating techniques for building search strategies or the use of specific database filters (e.g., use of Boolean operators or search filters for randomized controlled trials), examining various tools used for RoB or CoE assessment (e.g., ROBINS vs. Cochrane RoB tool), or evaluating statistical techniques used in meta‐analyses were excluded. 14

2.2. Search

The search for published SRs was performed on the following scientific databases initially from inception to third week of November 2020 and updated in the last week of February 2022: MEDLINE (via Ovid), Embase (via Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and American Psychological Association (APA) PsycINFO. Search was restricted to English language publications. Following the objectives of this study, study design filters within databases were used to restrict the search to SRs and MA, where available. The reference lists of included SRs were also searched for potentially relevant publications.

The search terms included keywords, truncations, and subject headings for the key concepts in the review question: SRs and/or MA, methods, and evaluation. Some of the terms were adopted from the search strategy used in a previous review by Robson et al., which reviewed primary studies on methodological approaches used in study selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal steps of SR process. 14 Individual search strategies were developed for respective databases by combining the search terms using appropriate proximity and Boolean operators, along with the related subject headings in order to identify SRs and/or MA. 16 , 17 A senior librarian was consulted in the design of the search terms and strategy. Appendix A presents the detailed search strategies for all five databases.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

Title and abstract screening of references were performed in three steps. First, one reviewer (PV) screened all the titles and excluded obviously irrelevant citations, for example, articles on topics not related to SRs, non‐SR publications (such as randomized controlled trials, observational studies, scoping reviews, etc.). Next, from the remaining citations, a random sample of 200 titles and abstracts were screened against the predefined eligibility criteria by two reviewers (PV and MM), independently, in duplicate. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. This step ensured that the responses of the two reviewers were calibrated for consistency in the application of the eligibility criteria in the screening process. Finally, all the remaining titles and abstracts were reviewed by a single “calibrated” reviewer (PV) to identify potential full‐text records. Full‐text screening was performed by at least two authors independently (PV screened all the records, and duplicate assessment was conducted by MM, HC, or MG), with discrepancies resolved via discussions or by consulting a third reviewer.

Data related to review characteristics, results, key findings, and conclusions were extracted by at least two reviewers independently (PV performed data extraction for all the reviews and duplicate extraction was performed by AP, HC, or MG).

2.4. Quality assessment of included reviews

The quality assessment of the included SRs was performed using the AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews). The tool consists of a 16‐item checklist addressing critical and noncritical domains. 18 For the purpose of this study, the domain related to MA was reclassified from critical to noncritical, as SRs with and without MA were included. The other six critical domains were used according to the tool guidelines. 18 Two reviewers (PV and AP) independently responded to each of the 16 items in the checklist with either “yes,” “partial yes,” or “no.” Based on the interpretations of the critical and noncritical domains, the overall quality of the review was rated as high, moderate, low, or critically low. 18 Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

2.5. Data synthesis

To provide an understandable summary of existing evidence syntheses, characteristics of the methods evaluated in the included SRs were examined and key findings were categorized and presented based on the corresponding step in the SR process. The categories of key elements within each step were discussed and agreed by the authors. Results of the included reviews were tabulated and summarized descriptively, along with a discussion on any overlap in the primary studies. 15 No quantitative analyses of the data were performed.

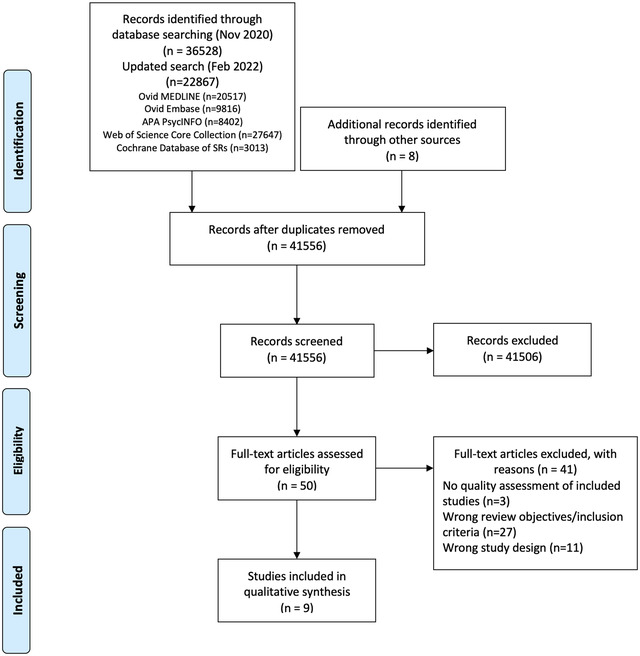

From 41,556 unique citations identified through literature search, 50 full‐text records were reviewed, and nine systematic reviews 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 were deemed eligible for inclusion. The flow of studies through the screening process is presented in Figure 1 . A list of excluded studies with reasons can be found in Appendix B .

Study selection flowchart

3.1. Characteristics of included reviews

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included SRs. The majority of the included reviews (six of nine) were published after 2010. 14 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Four of the nine included SRs were Cochrane reviews. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 The number of databases searched in the reviews ranged from 2 to 14, 2 reviews searched gray literature sources, 24 , 25 and 7 reviews included a supplementary search strategy to identify relevant literature. 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 26 Three of the included SRs (all Cochrane reviews) included an integrated MA. 20 , 21 , 23

Characteristics of included studies

SR = systematic review; MA = meta‐analysis; RCT = randomized controlled trial; CCT = controlled clinical trial; N/R = not reported.

The included SRs evaluated 24 unique methodological approaches (26 in total) used across five steps in the SR process; 8 SRs evaluated 6 approaches, 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 while 1 review evaluated 18 approaches. 14 Exclusion of gray or unpublished literature 21 , 26 and blinding of reviewers for RoB assessment 14 , 23 were evaluated in two reviews each. Included SRs evaluated methods used in five different steps in the SR process, including methods used in defining the scope of review ( n = 3), literature search ( n = 3), study selection ( n = 2), data extraction ( n = 1), and RoB assessment ( n = 2) (Table 2 ).

Summary of findings from review evaluating systematic review methods

Includes databases (MEDLINE, Embase, PyscINFO, CINAHL, Biosis, CancerLIT, Cabnar, CENTRAL, Chirolars, HealthStar, SciCitIndex, Cochrane Central Trial Register), internet, and handsearching.

Includes MEDLINE, Embase, PsychLIT, PsychINFO, Lilac and Cochrane Central Trials Register; HSS‐Highly Sensitive Search; SR, systematic review; MA, meta‐analysis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RoB, risk of bias.

There was some overlap in the primary studies evaluated in the included SRs on the same topics: Schmucker et al. 26 and Hopewell et al. 21 ( n = 4), Hopewell et al. 20 and Crumley et al. 19 ( n = 30), and Robson et al. 14 and Morissette et al. 23 ( n = 4). There were no conflicting results between any of the identified SRs on the same topic.

3.2. Methodological quality of included reviews

Overall, the quality of the included reviews was assessed as moderate at best (Table 2 ). The most common critical weakness in the reviews was failure to provide justification for excluding individual studies (four reviews). Detailed quality assessment is provided in Appendix C .

3.3. Evidence on systematic review methods

3.3.1. methods for defining review scope and eligibility.

Two SRs investigated the effect of excluding data obtained from gray or unpublished sources on the pooled effect estimates of MA. 21 , 26 Hopewell et al. 21 reviewed five studies that compared the impact of gray literature on the results of a cohort of MA of RCTs in health care interventions. Gray literature was defined as information published in “print or electronic sources not controlled by commercial or academic publishers.” Findings showed an overall greater treatment effect for published trials than trials reported in gray literature. In a more recent review, Schmucker et al. 26 addressed similar objectives, by investigating gray and unpublished data in medicine. In addition to gray literature, defined similar to the previous review by Hopewell et al., the authors also evaluated unpublished data—defined as “supplemental unpublished data related to published trials, data obtained from the Food and Drug Administration or other regulatory websites or postmarketing analyses hidden from the public.” The review found that in majority of the MA, excluding gray literature had little or no effect on the pooled effect estimates. The evidence was limited to conclude if the data from gray and unpublished literature had an impact on the conclusions of MA. 26

Morrison et al. 24 examined five studies measuring the effect of excluding non‐English language RCTs on the summary treatment effects of SR‐based MA in various fields of conventional medicine. Although none of the included studies reported major difference in the treatment effect estimates between English only and non‐English inclusive MA, the review found inconsistent evidence regarding the methodological and reporting quality of English and non‐English trials. 24 As such, there might be a risk of introducing “language bias” when excluding non‐English language RCTs. The authors also noted that the numbers of non‐English trials vary across medical specialties, as does the impact of these trials on MA results. Based on these findings, Morrison et al. 24 conclude that literature searches must include non‐English studies when resources and time are available to minimize the risk of introducing “language bias.”

3.3.2. Methods for searching studies

Crumley et al. 19 analyzed recall (also referred to as “sensitivity” by some researchers; defined as “percentage of relevant studies identified by the search”) and precision (defined as “percentage of studies identified by the search that were relevant”) when searching a single resource to identify randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials, as opposed to searching multiple resources. The studies included in their review frequently compared a MEDLINE only search with the search involving a combination of other resources. The review found low median recall estimates (median values between 24% and 92%) and very low median precisions (median values between 0% and 49%) for most of the electronic databases when searched singularly. 19 A between‐database comparison, based on the type of search strategy used, showed better recall and precision for complex and Cochrane Highly Sensitive search strategies (CHSSS). In conclusion, the authors emphasize that literature searches for trials in SRs must include multiple sources. 19

In an SR comparing handsearching and electronic database searching, Hopewell et al. 20 found that handsearching retrieved more relevant RCTs (retrieval rate of 92%−100%) than searching in a single electronic database (retrieval rates of 67% for PsycINFO/PsycLIT, 55% for MEDLINE, and 49% for Embase). The retrieval rates varied depending on the quality of handsearching, type of electronic search strategy used (e.g., simple, complex or CHSSS), and type of trial reports searched (e.g., full reports, conference abstracts, etc.). The authors concluded that handsearching was particularly important in identifying full trials published in nonindexed journals and in languages other than English, as well as those published as abstracts and letters. 20

The effectiveness of checking reference lists to retrieve additional relevant studies for an SR was investigated by Horsley et al. 22 The review reported that checking reference lists yielded 2.5%–40% more studies depending on the quality and comprehensiveness of the electronic search used. The authors conclude that there is some evidence, although from poor quality studies, to support use of checking reference lists to supplement database searching. 22

3.3.3. Methods for selecting studies

Three approaches relevant to reviewer characteristics, including number, experience, and blinding of reviewers involved in the screening process were highlighted in an SR by Robson et al. 14 Based on the retrieved evidence, the authors recommended that two independent, experienced, and unblinded reviewers be involved in study selection. 14 A modified approach has also been suggested by the review authors, where one reviewer screens and the other reviewer verifies the list of excluded studies, when the resources are limited. It should be noted however this suggestion is likely based on the authors’ opinion, as there was no evidence related to this from the studies included in the review.

Robson et al. 14 also reported two methods describing the use of technology for screening studies: use of Google Translate for translating languages (for example, German language articles to English) to facilitate screening was considered a viable method, while using two computer monitors for screening did not increase the screening efficiency in SR. Title‐first screening was found to be more efficient than simultaneous screening of titles and abstracts, although the gain in time with the former method was lesser than the latter. Therefore, considering that the search results are routinely exported as titles and abstracts, Robson et al. 14 recommend screening titles and abstracts simultaneously. However, the authors note that these conclusions were based on very limited number (in most instances one study per method) of low‐quality studies. 14

3.3.4. Methods for data extraction

Robson et al. 14 examined three approaches for data extraction relevant to reviewer characteristics, including number, experience, and blinding of reviewers (similar to the study selection step). Although based on limited evidence from a small number of studies, the authors recommended use of two experienced and unblinded reviewers for data extraction. The experience of the reviewers was suggested to be especially important when extracting continuous outcomes (or quantitative) data. However, when the resources are limited, data extraction by one reviewer and a verification of the outcomes data by a second reviewer was recommended.

As for the methods involving use of technology, Robson et al. 14 identified limited evidence on the use of two monitors to improve the data extraction efficiency and computer‐assisted programs for graphical data extraction. However, use of Google Translate for data extraction in non‐English articles was not considered to be viable. 14 In the same review, Robson et al. 14 identified evidence supporting contacting authors for obtaining additional relevant data.

3.3.5. Methods for RoB assessment

Two SRs examined the impact of blinding of reviewers for RoB assessments. 14 , 23 Morissette et al. 23 investigated the mean differences between the blinded and unblinded RoB assessment scores and found inconsistent differences among the included studies providing no definitive conclusions. Similar conclusions were drawn in a more recent review by Robson et al., 14 which included four studies on reviewer blinding for RoB assessment that completely overlapped with Morissette et al. 23

Use of experienced reviewers and provision of additional guidance for RoB assessment were examined by Robson et al. 14 The review concluded that providing intensive training and guidance on assessing studies reporting insufficient data to the reviewers improves RoB assessments. 14 Obtaining additional data related to quality assessment by contacting study authors was also found to help the RoB assessments, although based on limited evidence. When assessing the qualitative or mixed method reviews, Robson et al. 14 recommends the use of a structured RoB tool as opposed to an unstructured tool. No SRs were identified on data synthesis and CoE assessment and reporting steps.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. summary of findings.

Nine SRs examining 24 unique methods used across five steps in the SR process were identified in this overview. The collective evidence supports some current traditional and modified SR practices, while challenging other approaches. However, the quality of the included reviews was assessed to be moderate at best and in the majority of the included SRs, evidence related to the evaluated methods was obtained from very limited numbers of primary studies. As such, the interpretations from these SRs should be made cautiously.

The evidence gathered from the included SRs corroborate a few current SR approaches. 5 For example, it is important to search multiple resources for identifying relevant trials (RCTs and/or CCTs). The resources must include a combination of electronic database searching, handsearching, and reference lists of retrieved articles. 5 However, no SRs have been identified that evaluated the impact of the number of electronic databases searched. A recent study by Halladay et al. 27 found that articles on therapeutic intervention, retrieved by searching databases other than PubMed (including Embase), contributed only a small amount of information to the MA and also had a minimal impact on the MA results. The authors concluded that when the resources are limited and when large number of studies are expected to be retrieved for the SR or MA, PubMed‐only search can yield reliable results. 27

Findings from the included SRs also reiterate some methodological modifications currently employed to “expedite” the SR process. 10 , 11 For example, excluding non‐English language trials and gray/unpublished trials from MA have been shown to have minimal or no impact on the results of MA. 24 , 26 However, the efficiency of these SR methods, in terms of time and the resources used, have not been evaluated in the included SRs. 24 , 26 Of the SRs included, only two have focused on the aspect of efficiency 14 , 25 ; O'Mara‐Eves et al. 25 report some evidence to support the use of text‐mining approaches for title and abstract screening in order to increase the rate of screening. Moreover, only one included SR 14 considered primary studies that evaluated reliability (inter‐ or intra‐reviewer consistency) and accuracy (validity when compared against a “gold standard” method) of the SR methods. This can be attributed to the limited number of primary studies that evaluated these outcomes when evaluating the SR methods. 14 Lack of outcome measures related to reliability, accuracy, and efficiency precludes making definitive recommendations on the use of these methods/modifications. Future research studies must focus on these outcomes.

Some evaluated methods may be relevant to multiple steps; for example, exclusions based on publication status (gray/unpublished literature) and language of publication (non‐English language studies) can be outlined in the a priori eligibility criteria or can be incorporated as search limits in the search strategy. SRs included in this overview focused on the effect of study exclusions on pooled treatment effect estimates or MA conclusions. Excluding studies from the search results, after conducting a comprehensive search, based on different eligibility criteria may yield different results when compared to the results obtained when limiting the search itself. 28 Further studies are required to examine this aspect.

Although we acknowledge the lack of standardized quality assessment tools for methodological study designs, we adhered to the Cochrane criteria for identifying SRs in this overview. This was done to ensure consistency in the quality of the included evidence. As a result, we excluded three reviews that did not provide any form of discussion on the quality of the included studies. The methods investigated in these reviews concern supplementary search, 29 data extraction, 12 and screening. 13 However, methods reported in two of these three reviews, by Mathes et al. 12 and Waffenschmidt et al., 13 have also been examined in the SR by Robson et al., 14 which was included in this overview; in most instances (with the exception of one study included in Mathes et al. 12 and Waffenschmidt et al. 13 each), the studies examined in these excluded reviews overlapped with those in the SR by Robson et al. 14

One of the key gaps in the knowledge observed in this overview was the dearth of SRs on the methods used in the data synthesis component of SR. Narrative and quantitative syntheses are the two most commonly used approaches for synthesizing data in evidence synthesis. 5 There are some published studies on the proposed indications and implications of these two approaches. 30 , 31 These studies found that both data synthesis methods produced comparable results and have their own advantages, suggesting that the choice of the method must be based on the purpose of the review. 31 With increasing number of “expedited” SR approaches (so called “rapid reviews”) avoiding MA, 10 , 11 further research studies are warranted in this area to determine the impact of the type of data synthesis on the results of the SR.

4.2. Implications for future research

The findings of this overview highlight several areas of paucity in primary research and evidence synthesis on SR methods. First, no SRs were identified on methods used in two important components of the SR process, including data synthesis and CoE and reporting. As for the included SRs, a limited number of evaluation studies have been identified for several methods. This indicates that further research is required to corroborate many of the methods recommended in current SR guidelines. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Second, some SRs evaluated the impact of methods on the results of quantitative synthesis and MA conclusions. Future research studies must also focus on the interpretations of SR results. 28 , 32 Finally, most of the included SRs were conducted on specific topics related to the field of health care, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other areas. It is important that future research studies evaluating evidence syntheses broaden the objectives and include studies on different topics within the field of health care.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first overview summarizing current evidence from SRs and MA on different methodological approaches used in several fundamental steps in SR conduct. The overview methodology followed well established guidelines and strict criteria defined for the inclusion of SRs.

There are several limitations related to the nature of the included reviews. Evidence for most of the methods investigated in the included reviews was derived from a limited number of primary studies. Also, the majority of the included SRs may be considered outdated as they were published (or last updated) more than 5 years ago 33 ; only three of the nine SRs have been published in the last 5 years. 14 , 25 , 26 Therefore, important and recent evidence related to these topics may not have been included. Substantial numbers of included SRs were conducted in the field of health, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Some method evaluations in the included SRs focused on quantitative analyses components and MA conclusions only. As such, the applicability of these findings to SR more broadly is still unclear. 28 Considering the methodological nature of our overview, limiting the inclusion of SRs according to the Cochrane criteria might have resulted in missing some relevant evidence from those reviews without a quality assessment component. 12 , 13 , 29 Although the included SRs performed some form of quality appraisal of the included studies, most of them did not use a standardized RoB tool, which may impact the confidence in their conclusions. Due to the type of outcome measures used for the method evaluations in the primary studies and the included SRs, some of the identified methods have not been validated against a reference standard.

Some limitations in the overview process must be noted. While our literature search was exhaustive covering five bibliographic databases and supplementary search of reference lists, no gray sources or other evidence resources were searched. Also, the search was primarily conducted in health databases, which might have resulted in missing SRs published in other fields. Moreover, only English language SRs were included for feasibility. As the literature search retrieved large number of citations (i.e., 41,556), the title and abstract screening was performed by a single reviewer, calibrated for consistency in the screening process by another reviewer, owing to time and resource limitations. These might have potentially resulted in some errors when retrieving and selecting relevant SRs. The SR methods were grouped based on key elements of each recommended SR step, as agreed by the authors. This categorization pertains to the identified set of methods and should be considered subjective.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This overview identified limited SR‐level evidence on various methodological approaches currently employed during five of the seven fundamental steps in the SR process. Limited evidence was also identified on some methodological modifications currently used to expedite the SR process. Overall, findings highlight the dearth of SRs on SR methodologies, warranting further work to confirm several current recommendations on conventional and expedited SR processes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

APPENDIX A: Detailed search strategies

APPENDIX B: List of excluded studies with detailed reasons for exclusion

APPENDIX C: Quality assessment of included reviews using AMSTAR 2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first author is supported by a La Trobe University Full Fee Research Scholarship and a Graduate Research Scholarship.

Open Access Funding provided by La Trobe University.

Veginadu P, Calache H, Gussy M, Pandian A, Masood M. An overview of methodological approaches in systematic reviews. J Evid Based Med. 2022;15:39–54. 10.1111/jebm.12468

- 1. Ioannidis JPA. Evolution and translation of research findings: from bench to where. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1(7), e36. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Crocetti E. Systematic reviews with meta‐analysis:why, when, and how? Emerg Adulthood. 2016;4(1):3–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7), e1000097. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Akers J. Systematic Reviews: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. CRD, University of York; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3. Cochrane; 2022. http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook . [updated February 2022]. Available from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Joanna Briggs Institute . Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition/Supplement. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Methods Group of the Campbell Collaboration . Methodological expectations of Campbell Collaboration intervention reviews: Conduct standards . 2016.

- 8. Chandler J, Hopewell S. Cochrane methods—twenty years experience in developing systematic review methods. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):76. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Tsertsvadze A, Chen Y‐F, Moher D, Sutcliffe P, McCarthy N. How to conduct systematic reviews more expeditiously? Syst Rev. 2015;4: 160–160. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci. 2010;5: 56. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Mathes T, Klasen P, Pieper D. Frequency of data extraction errors and methods to increase data extraction quality: a methodological review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):152. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Waffenschmidt S, Knelangen M, Sieben W, Buhn S, Pieper D. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: a methodological systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:132. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Robson RC, Pham B, Hwee J, et al. Few studies exist examining methods for selecting studies, abstracting data, and appraising quality in a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;106: 121–135. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: overviews of reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane; 2022. Available from: http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Montori VM, Wilczynski NL, Morgan D, Haynes RB. Optimal search strategies for retrieving systematic reviews from Medline: analytical survey. BMJ. 2005;330(7482):68. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. EMBASE search strategies achieved high sensitivity and specificity for retrieving methodologically sound systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):29–33. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non‐randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358: j4008. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Crumley ET, Wiebe N, Cramer K, Klassen TP, Hartling L. Which resources should be used to identify RCT/CCTs for systematic reviews: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5: 24. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Hopewell S, Clarke MJ, Lefebvre C, Scherer RW. Handsearching versus electronic searching to identify reports of randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007(2), MR000001. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Hopewell S, McDonald S, Clarke M, Egger M. Grey literature in meta‐analyses of randomized trials of health care interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(2), MR000010. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Horsley T, Dingwall O, Sampson M. Checking reference lists to find additional studies for systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(8), MR000026. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Morissette K, Tricco AC, Horsley T, Chen MH, Moher D. Blinded versus unblinded assessments of risk of bias in studies included in a systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(9), MR000025. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, et al. The effect of English‐language restriction on systematic review‐based meta‐analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(2):138–144. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. O'Mara‐Eves A, Thomas J, McNaught J, Miwa M, Ananiadou S. Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):5. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Schmucker CM, Blumle A, Schell LK, et al. Systematic review finds that study data not published in full text articles have unclear impact on meta‐analyses results in medical research. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2017;12(4), e0176210. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Halladay CW, Trikalinos TA, Schmid IT, Schmid CH, Dahabreh IJ. Using data sources beyond PubMed has a modest impact on the results of systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(9):1076–1084. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Nussbaumer‐Streit B, Klerings I, Dobrescu A, et al. Excluding non‐English publications from evidence‐syntheses did not change conclusions: a meta‐epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;118: 42–54. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Cooper C, Booth A, Britten N, Garside R. A comparison of results of empirical studies of supplementary search techniques and recommendations in review methodology handbooks: a methodological review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):234. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Melendez‐Torres GJ, O'Mara‐Eves A, Thomas J, Brunton G, Caird J, Petticrew M. Interpretive analysis of 85 systematic reviews suggests that narrative syntheses and meta‐analyses are incommensurate in argumentation. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8(1):109–118. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Melendez‐Torres GJ, Thomas J, Lorenc T, O'Mara‐Eves A, Petticrew M. Just how plain are plain tobacco packs: re‐analysis of a systematic review using multilevel meta‐analysis suggests lessons about the comparative benefits of synthesis methods. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):153. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Nussbaumer‐Streit B, Klerings I, Wagner G, et al. Abbreviated literature searches were viable alternatives to comprehensive searches: a meta‐epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;102: 1–11. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, Ji J, Doucette S, Moher D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(4):224–233. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (452.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Help us improve our Library guides with this 5 minute survey . We appreciate your feedback!

- UOW Library

- Key guides for researchers

Systematic Review

- Five other types of systematic review

- What is a systematic review?

- How is a literature review different?

- Search tips for systematic reviews

- Controlled vocabularies

- Grey literature

- Transferring your search

- Documenting your results

- Support & contact

Five other types of systematic reviews

1. scoping review.

A scoping review is a preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify the nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research).

Scoping reviews provide an understanding of the size and scope of the available literature and can inform whether a full systematic review should be undertaken.

If you're not sure you should conduct a systematic review or a scoping review, this article outlines the differences between these review types and could help your decision making.

2. Rapid review

Rapid reviews are an assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research.

This methodology utilises several legitimate techniques to shorten the process – careful focus of the research question, using broad or less sophisticated search strategies, conducting a review of reviews, restricting the amount of grey literature, extracting only key variables and performing more simple quality appraisals.

Rapid reviews have an increased risk of potential bias due to their short timeframe. Documenting the methodology and highlighting its limitations is one way to mitigate bias.

3. Narrative review

Also called a literature review.

A narrative, or literature, review synthesises primary studies and explores this through description rather than statistics. Library support for literature review can be found in this guide .

4. Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect on the results. This type of study examines data from multiple studies, on the same subject, to determine trends.

Outcomes from a meta-analysis may include a more precise estimate of the effect of treatment or risk factor for disease, or other outcomes, than any individual study contributing to the combined studies being analysed.

5. Mixed methods/mixed studies

Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic review). For example, a mixed methods study might include a systematic review accompanied by interviews or by a stakeholder consultation.

Within a review context, mixed methods studies refers to a combination of review approaches. For example, combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies.

Further reading:

- Duke University, Types of Reviews

- Systematic review types: meet the family (Covidence)

- Systematic reviews and other types from Temple University

- A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies (Grant & Booth, 2009).

- Previous: What is a systematic review?

- Next: How is a literature review different?

- Last Updated: Sep 11, 2024 7:40 AM

- URL: https://uow.libguides.com/systematic-review

Insert research help text here

LIBRARY RESOURCES

Library homepage

Library SEARCH

A-Z Databases

STUDY SUPPORT

Academic Skills Centre

Referencing and citing

Digital Skills Hub

MORE UOW SERVICES

UOW homepage

Student support and wellbeing

IT Services

On the lands that we study, we walk, and we live, we acknowledge and respect the traditional custodians and cultural knowledge holders of these lands.

Copyright & disclaimer | Privacy & cookie usage

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Published on 15 June 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on 18 July 2024.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesise all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question ‘What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?’

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs meta-analysis, systematic review vs literature review, systematic review vs scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce research bias . The methods are repeatable , and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesise the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesising all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesising means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesise the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesise results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarise and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimise bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimise research b ias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinised by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarise all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fourth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomised control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective(s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesise the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Grey literature: Grey literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of grey literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of grey literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Grey literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarise what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgement of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomised into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesise the data

Synthesising the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesising the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarise the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarise and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analysed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Turney, S. (2024, July 17). Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 16 December 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/systematic-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, exploratory research | definition, guide, & examples, what is peer review | types & examples.

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Introduction to Systematic Review

- Introduction

- Types of literature reviews

- Other Libguides

- Systematic review as part of a dissertation

- Tutorials & Guidelines & Examples from non-Medical Disciplines

Depending on your learning style, please explore the resources in various formats on the tabs above.

For additional tutorials, visit the SR Workshop Videos from UNC at Chapel Hill outlining each stage of the systematic review process.

Know the difference! Systematic review vs. literature review

Types of literature reviews along with associated methodologies

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis . Find definitions and methodological guidance.

- Systematic Reviews - Chapters 1-7

- Mixed Methods Systematic Reviews - Chapter 8

- Diagnostic Test Accuracy Systematic Reviews - Chapter 9

- Umbrella Reviews - Chapter 10

- Scoping Reviews - Chapter 11

- Systematic Reviews of Measurement Properties - Chapter 12

Systematic reviews vs scoping reviews -

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal , 26 (2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1 (28). htt p s://doi.org/ 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

Munn, Z., Peters, M., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review ? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology, 18 (1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. Also, check out the Libguide from Weill Cornell Medicine for the differences between a systematic review and a scoping review and when to embark on either one of them.

Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., & Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: Exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements . Health Information & Libraries Journal , 36 (3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12276

Temple University. Review Types . - This guide provides useful descriptions of some of the types of reviews listed in the above article.

UMD Health Sciences and Human Services Library. Review Types . - Guide describing Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and Rapid Reviews.

Whittemore, R., Chao, A., Jang, M., Minges, K. E., & Park, C. (2014). Methods for knowledge synthesis: An overview. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 43 (5), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.014

Differences between a systematic review and other types of reviews

Armstrong, R., Hall, B. J., Doyle, J., & Waters, E. (2011). ‘ Scoping the scope ’ of a cochrane review. Journal of Public Health , 33 (1), 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

Kowalczyk, N., & Truluck, C. (2013). Literature reviews and systematic reviews: What is the difference? Radiologic Technology , 85 (2), 219–222.

White, H., Albers, B., Gaarder, M., Kornør, H., Littell, J., Marshall, Z., Matthew, C., Pigott, T., Snilstveit, B., Waddington, H., & Welch, V. (2020). Guidance for producing a Campbell evidence and gap map . Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16 (4), e1125. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1125. Check also this comparison between evidence and gaps maps and systematic reviews.

Rapid Reviews Tutorials

Rapid Review Guidebook by the National Collaborating Centre of Methods and Tools (NCCMT)

Hamel, C., Michaud, A., Thuku, M., Skidmore, B., Stevens, A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., & Garritty, C. (2021). Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology , 129 , 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.041

- Müller, C., Lautenschläger, S., Meyer, G., & Stephan, A. (2017). Interventions to support people with dementia and their caregivers during the transition from home care to nursing home care: A systematic review . International Journal of Nursing Studies, 71 , 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.03.013

- Bhui, K. S., Aslam, R. W., Palinski, A., McCabe, R., Johnson, M. R. D., Weich, S., … Szczepura, A. (2015). Interventions to improve therapeutic communications between Black and minority ethnic patients and professionals in psychiatric services: Systematic review . The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207 (2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158899

- Rosen, L. J., Noach, M. B., Winickoff, J. P., & Hovell, M. F. (2012). Parental smoking cessation to protect young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Pediatrics, 129 (1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3209

Scoping Review

- Hyshka, E., Karekezi, K., Tan, B., Slater, L. G., Jahrig, J., & Wild, T. C. (2017). The role of consumer perspectives in estimating population need for substance use services: A scoping review . BMC Health Services Research, 171-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2153-z

- Olson, K., Hewit, J., Slater, L.G., Chambers, T., Hicks, D., Farmer, A., & ... Kolb, B. (2016). Assessing cognitive function in adults during or following chemotherapy: A scoping review . Supportive Care In Cancer, 24 (7), 3223-3234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3215-1

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency . Research Synthesis Methods, 5 (4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Scoping Review Tutorial from UNC at Chapel Hill

Qualitative Systematic Review/Meta-Synthesis

- Lee, H., Tamminen, K. A., Clark, A. M., Slater, L., Spence, J. C., & Holt, N. L. (2015). A meta-study of qualitative research examining determinants of children's independent active free play . International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 12 (5), 121-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0165-9

Videos on systematic reviews

Systematic Reviews: What are they? Are they right for my research? - 47 min. video recording with a closed caption option.

More training videos on systematic reviews:

Books on Systematic Reviews

Books on Meta-analysis

- University of Toronto Libraries - very detailed with good tips on the sensitivity and specificity of searches.

- Monash University - includes an interactive case study tutorial.

- Dalhousie University Libraries - a comprehensive How-To Guide on conducting a systematic review.

Guidelines for a systematic review as part of the dissertation

- Guidelines for Systematic Reviews in the Context of Doctoral Education Background by University of Victoria (PDF)

- Can I conduct a Systematic Review as my Master’s dissertation or PhD thesis? Yes, It Depends! by Farhad (blog)

- What is a Systematic Review Dissertation Like? by the University of Edinburgh (50 min video)

Further readings on experiences of PhD students and doctoral programs with systematic reviews

Puljak, L., & Sapunar, D. (2017). Acceptance of a systematic review as a thesis: Survey of biomedical doctoral programs in Europe . Systematic Reviews , 6 (1), 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0653-x

Perry, A., & Hammond, N. (2002). Systematic reviews: The experiences of a PhD Student . Psychology Learning & Teaching , 2 (1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2002.2.1.32

Daigneault, P.-M., Jacob, S., & Ouimet, M. (2014). Using systematic review methods within a Ph.D. dissertation in political science: Challenges and lessons learned from practice . International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 17 (3), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.730704

UMD Doctor of Philosophy Degree Policies

Before you embark on a systematic review research project, check the UMD PhD Policies to make sure you are on the right path. Systematic reviews require a team of at least two reviewers and an information specialist or a librarian. Discuss with your advisor the authorship roles of the involved team members. Keep in mind that the UMD Doctor of Philosophy Degree Policies (scroll down to the section, Inclusion of one's own previously published materials in a dissertation ) outline such cases, specifically the following:

" It is recognized that a graduate student may co-author work with faculty members and colleagues that should be included in a dissertation . In such an event, a letter should be sent to the Dean of the Graduate School certifying that the student's examining committee has determined that the student made a substantial contribution to that work. This letter should also note that the inclusion of the work has the approval of the dissertation advisor and the program chair or Graduate Director. The letter should be included with the dissertation at the time of submission. The format of such inclusions must conform to the standard dissertation format. A foreword to the dissertation, as approved by the Dissertation Committee, must state that the student made substantial contributions to the relevant aspects of the jointly authored work included in the dissertation."

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions - See Part 2: General methods for Cochrane reviews

- Systematic Searches - Yale library video tutorial series

- Using PubMed's Clinical Queries to Find Systematic Reviews - From the U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A step-by-step guide - From the University of Edinsburgh, Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology

Bioinformatics

- Mariano, D. C., Leite, C., Santos, L. H., Rocha, R. E., & de Melo-Minardi, R. C. (2017). A guide to performing systematic literature reviews in bioinformatics . arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.05813.

Environmental Sciences